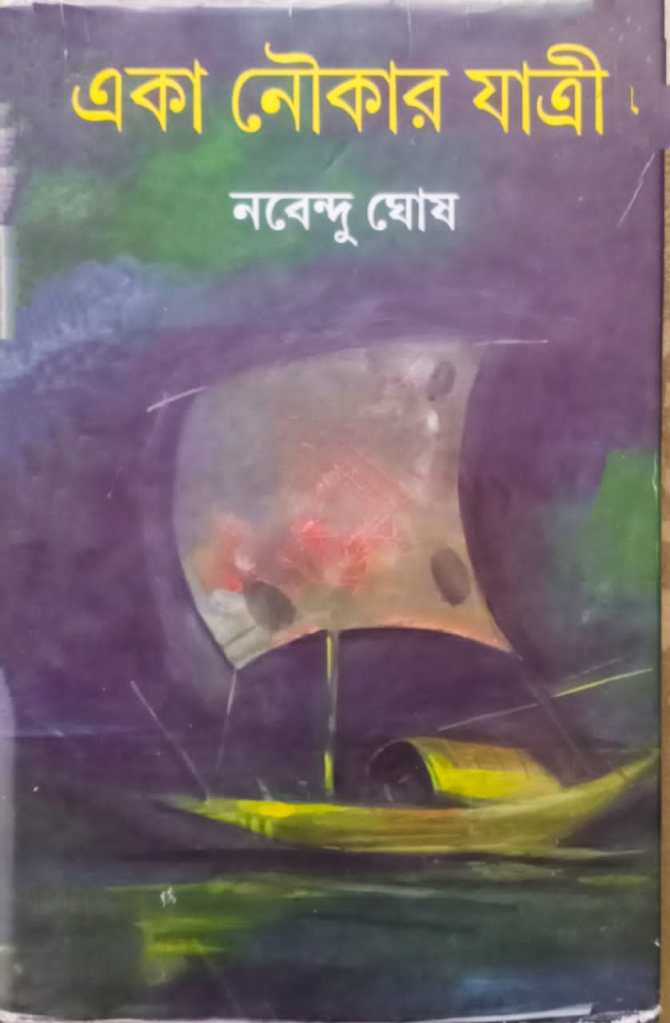

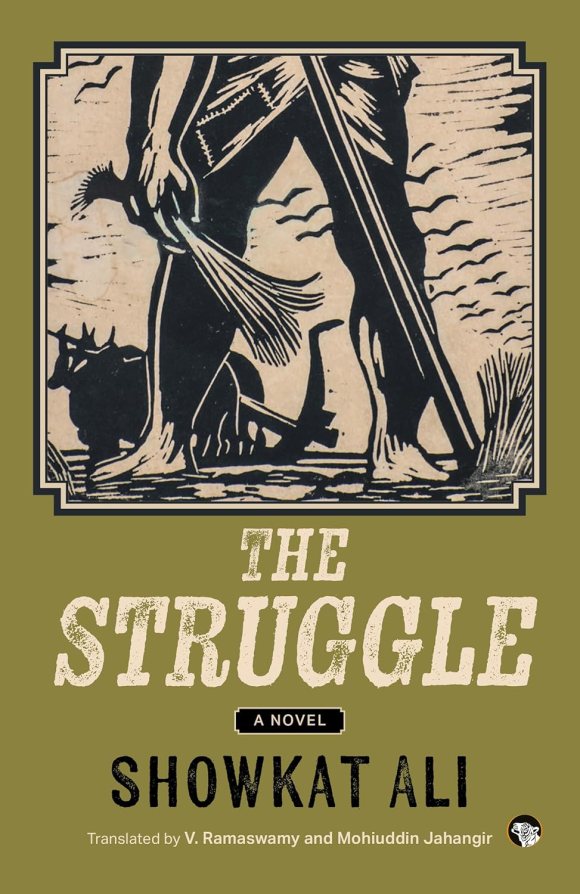

Title: The Struggle: A Novel

Author: Showkat Ali

Translators: V. Ramaswamy and Mohiuddin Jahangir

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

It was being said that the landlords were terribly angry, and that apparently they would not let the sharecroppers harvest the paddy. The paddy would be cut by people brought from outside. If there was a conflict over the matter, only Allah knew what would happen. Phulmoti did not know any prayers or Quranic verses; ‘Allah’ and ‘Bismillahe Rahamanur Rahim’ were the only sacred words she knew. She inwardly uttered those whenever the fear overwhelmed her.

One morning, Qutubali suddenly spotted someone in the distance, running along the boundary ridge towards their house. The person appeared familiar. So, he kept looking, trying to make out who it was. And why on earth was he running like that?

He recognized the man soon enough. ‘Aare, it is Mahindar!’ Qutubali advanced. Gasping for breath, Mahindar informed him that he had been to Ranisankoil to meet the peasants’ union there. He said he saw many men from Bihar at Pirganj station. They had long-moustachioed faces, and were hefty of build, and they were all carrying long lathis with a brass grip. He had heard that they were going to the house of the landlord Mitra Babu of Ranisankoil to guard the paddy fields. Apparently, thieves were cutting the paddy and taking it away and so the paddy on his field had to be guarded.

Qutubali grew anxious when he heard the news. Both of them rushed to the market, discussing the matter as they went. If the landlords in their locality too brought in Bihari watchmen from the west and made them guard the paddy fields, what would the peasants do? Would the watchmen let the sharecroppers cut the paddy? And what if they did not? Would the sharecropping peasants sit idly by with folded hands? The plough and the bullocks belonged to the sharecropper; he was the one who toiled, and it was he who raised the crop. Would he have no claim over that crop now? Would they not permit him to even enter the crop field? What nonsense was this? Hired musclemen from Bihar to guard ripe paddy in the fields was simply unacceptable!

Both of them were in agreement. No, the sharecroppers would cut the paddy. If there was resistance, then a fight would break out, and if indeed it did, then they must fight.

‘There’s no option but to fight,’ Mahindar said. ‘Let anyone say what they want, but we must fight.’

When they reached the union office, they saw that Baram Horo was already there, puffing on a beedi. He was surprised to see the two of them.

‘You people? Where’s Mondol? And Dinesh?’

Qutubali and Mahindar were startled. ‘Why, was Delbar Mondol supposed to come here?’

‘Yes,’ Baram said. ‘Dinesh asked Mondol to come. He needs to be here.’

‘Why? What happened?’

The news wasn’t good, Baram informed them. ‘Instructions have been received in all the police stations that since the paddy in the landlords’ fields might be looted, the police must guard the paddy with rifles until the harvest is over. I think they won’t let the sharecropping peasants cut the paddy.’

They didn’t realize how quickly the day passed—it was already afternoon. A lot of people had joined them by now. All were sharecropping peasants, except for Dr Abhimanyu Sen. There were discussions and information was shared. No one could say what the district-level leaders had decided.

‘They will decide what they think is appropriate,’ Doctor Babu said, ‘but will we sit twiddling our thumbs because of that? The landlords are bringing musclemen. We can’t bring guns, but we too have to pick up lathis. This isn’t anything new; the peasant earlier carried a cattle-prod, now he’ll carry a six-foot-long lathi of seasoned bamboo. Go, brothers, go and cut lathis from bamboo clumps…’

Dinesh Murmu kept shaking his head, growling, ‘What rubbish is this! Saala, the government, police and political parties are all on the side of the landlords. No one is on our side.’

The stalks full of ears of ripe paddy stood all over the floodplain with their heads bowed, waiting for the festival of harvest to begin! But the festive moment never arrived.

Qutubali was unable to sleep. Countless millions of stars shed dew smeared with blue light as the night advanced towards the next horizon. From many faraway fields could be heard the cries of ‘Hoshiyar…jaagte raho—o—o… Beware, stay awake!’ He had seen with his own eyes that Ghosh Babu too had brought a hired band of Bihari guards from Purnea district. He had no idea whose counsel the Mistress had followed in taking this step. Was she planning on getting the paddy cutting done by someone else? What about the task of husking the paddy? That too?

His wife was asleep next to him, as was his son, but he remained awake.

At some point during those still hours, Doctor Babu arrived at their house on a bicycle. He gave clear instructions: Delbar Mondol and Mahindar Burman were not to remain at home at night, nor were they to set foot in the nearby town or the marketplace in the market town. If they did, they might be arrested by the police and sent to jail. Doctor Babu also conveyed the news that the police had gone to arrest Dinesh and Baram, but fortunately, they couldn’t. Having got the news, the two had gone into hiding.

‘We are not going to start fighting just now…that’s right… but that doesn’t mean that we will let the police catch us,’ Doctor Babu said. ‘We will be careful and keep ourselves safe. And we will cut the paddy and bring it home—we must keep that in mind.’

No cutting of the paddy, no ploughing of the soil for the next crop, just sitting and waiting! If the ears dried up, would the paddy be fit to cut? All the stalks would drop off their ears.

Extracted from The Struggle: A Novel by Showkat Ali, translated by V. Ramaswamy and Mohiuddin Jahangir. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2025.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Set in a remote village in the Dinajpur region of undivided Bengal during the mid-1940s, The Struggle tells the intertwined story of Phulmoti—a young widow fighting to hold on to her land, her dignity and her child—and Qutubali, a simple-minded outsider whose unexpected kindness and fierce loyalty make him her unlikely ally amid the upheavals of a precarious feudal order and the stirrings of a nation on the verge of independence.

The death of Phulmoti’s husband shatters her fragile world. Her ten-year-old, Abed, can offer little defence against the men now circling her—neighbours, relatives, even the local cleric—drawn by desire and the lure of her small property. Malek, a kindly bookseller at the local market, too, proves not to be what he seems. It is Malek’s hired hand, Qutubali, who finds himself drawn into her struggles, standing by her in ways that others do not. The politics of the Congress and the Muslim League hover on the margins of village life, far removed from their daily battles. But when the tebhaga struggle breaks out in Bengal—with sharecroppers demanding two-thirds of the harvest from landlords as their rightful due—Phulmoti and Qutubali stand to lose what little of their lives they have pieced back together.

First published in 1989 as Narai, this novel is not only a vivid portrayal of endurance in the face of isolation and rural exploitation, but also a sharp indictment of the social and political systems that deny justice to the poor. This sensitive translation introduces to a wider audience a forgotten classic of Bengali literature—politically clear-eyed and deeply moving.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Showkat Ali (1936–2018) was a renowned Bangladeshi novelist, short story writer and journalist whose work explored history, class and identity in Bengali society. His most celebrated novel, Prodoshe Prakritojon (1984), is considered a landmark in Bangladeshi literature.

ABOUT THE TRANSLATORS

Mohiuddin Jahangir is currently Assistant Professor in Khabashpur Adarsa University College, Bangladesh. His articles on literature, history and heritage have been published in scholarly journals, and he is the author of seven books.

V. Ramaswamy has translated many well-known Benglai authors. He was awarded the Translation Fellowship by the New India Foundation, and the English PEN Presents award in 2022.

Click here to read the review of the novel

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL