La Tauromaquia. Leap with the Spear by Picasso (1881-1973)

There was a time when there were no boundaries drawn by humans. Our ancestors roamed the Earth like any other fauna — part of nature and the landscape. They tried to explain and appease the changing seasons, the altering landscapes and the elements that affected life and living with rituals that seemed coherent to them. There were probably no major organised structures that laid out rules. From such observances, our festivals evolved to what we celebrate today. These celebrations are not just full of joie de vivre, but also a reminder of our syncretic start that diverged into what currently seems to be irreparable breaches and a lifestyle that is in conflict with the needs of our home planet.

Reflecting on this tradition of syncretism in our folklore and music, while acknowledging the boundaries that wreak havoc, is an essay by Aruna Chakravarti. She expounds on rituals that were developed to appease natural forces spreading diseases and devastation, celebrations that bring joy with harvests and override the narrowness of institutionalised human construct. She concludes with Lalan Fakir’s life as emblematic of the syncretic lore. Lalan, an uneducated man brought to limelight by the Tagore family, swept across religious divides with his immortal lyrics full of wisdom and simplicity. Dyed in similar syncretic lore are the writings of a student and disciple of Tagore from Santiniketan, Syed Mujtaba Ali (1904-1974). His works overriding these artificial constructs have been brought to light, by his translator, former BBC editor, Nazes Afroz. Having translated his earlier book, In a Land Far from Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan, Afroz has now brought to us Syed Mujtaba Ali’s Tales of a Voyager (Jolay Dangay), in which we read of his travels to Egypt almost ninety years ago. In his interview, the translator highlights the current relevance of this remarkable polyglot.

Humming the tunes of Mujtaba Ali’s tutor, Tagore, a translation of Tagore’s song, Amra Beddhechhi Kasher Guchho (We have Tied Bunches of Kash[1]) captures the spirit of autumnal opulence which heralds the advent of Durga Puja. A translation by Fazal Baloch has brought a message of non-violence very aptly in these times from recently deceased eminent Balochi poet, Mubarak Qazi. Professor Fakrul Alam has translated a very contemporary poem by Quazi Johirul Islam on Barnes and Nobles while from Korea, we have a translation of a poem by Ihlwha Choi on the fruit, jujube, which is eaten fresh of the tree in autumn.

A poem which starts with a translation of a Tang dynasty’s poet, Yuan Zhen, inaugurates the first translation we have had from Mandarin — though it’s just two paras by the poet, Rex Tan, who continues writing his response to the Chinese poem in English. Mingling nature and drawing life lessons from it are poems by George Freek, Ryan Quinn Flanagan and Gopal Lahiri. We have poetry which enriches our treasury by its sheer variety from Hawla Riza, Pramod Rastogi, John Zedolik, Avantika Vijay Singh, Tohm Bakelas and more. Michael Burch has brought in a note of festivities with his Halloween poems. And Rhys Hughes has rolled out humour with his observations on the city of Mysore. His column too this time has given us a table and a formula for writing humorous poetry — a tongue-in-cheek piece, just like the book excerpt from The Coffee Rubaiyat. In the original Rubaiyat, Omar Khayyam (1048–1131) had given us wonderful quatrains which Edward Fitzgerald immortalised with his nineteenth century translation from Persian to English and now, Hughes gives us a spoof which would well have you rollicking on the floor, and that too, only because as he tells us he prefers coffee over wine!

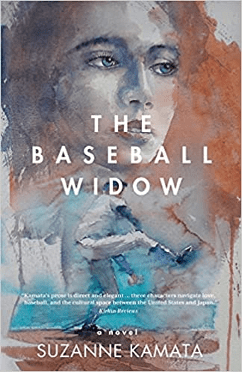

Humour tinged with irony is woven into Devraj Singh Kalsi’s narrative on red carpet welcomes in Indian weddings. We have a number of travel stories from Peru to all over the world. Ravi Shankar takes us to Lima and Meredith Stephens to Californian hot springs with photographs and narratives while Sayani De does the same for a Tibetan monastery in Lahaul. Keith Lyons converses with globe trotter Tomaž Serafi, who lives in Ljubljana. And Suzanne Kamata adds colour with a light-veined narrative on robots and baseball in Japan. Syncretic elements are woven by Dr. KPP Nambiar who made the first Japanese-Malyalam Dictionary. He started nearly fifty years ago after finding commonalities between the two cultures dating back to the sixteenth century. Tulip Chowdhury brings in colours of Halloween while discussing ghosts in Bangladesh and America, where she migrated.

The theme of immigration is taken up by Gemini Wahaaj as she reviews South to South: Writing South Asia in the American South edited by Khem K. Aryal. Japan again comes into focus with Aditi Yadav’s Makoto Shinkai’s and Naruki Nagakawa’s She and Her Cat, translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori. Somdatta Mandal has also reviewed a translation by no less than Booker winning Daisy Rockwell, who has translated Usha Priyamvada’s Won’t You Stay, Radhika? from Hindi. Our reviews seem full of translations this time as Bhaskar Parichha comments on One Among You: The Autobiography of M.K. Stalin, the current Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, translated from Tamil by A S Panneerselvan. In fiction, we have stories that add different flavours from Paul Mirabile, Neera Kashyap, Nirmala Pillai and more.

Our book excerpt from Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi’s Why didn’t You Come Sooner? Compassion in Action—Stories of Children Rescued from Slavery deserves a special mention. It showcases a world far removed from the one we know. While he was rescuing some disadvantaged children, Satyarthi relates his experience in the rescue van:

“One of the children gave it [the bunch of bananas] to the child sitting in front. An emaciated girl and a little boy were seated next to me. I told them to pass on the fruit to everyone in the back and keep one each for themselves. The girl looked curiously at the bunch as she turned it around in her hands. Then she looked at the other children. “‘I’ve never seen an onion like this one,’ she said. “Her little companion also touched the fruit gingerly and innocently added, ‘Yes, this is not even a potato.’ “I was speechless to say the least. These children had never seen anything apart from onions and potatoes. They had definitely never chanced upon bananas…”

Heart-wrenching but true! Maybe, we can all do our bit by reaching out to some outside our comfort or social zone to close such alarming gaps… Uma Dasgupta’s book tells us that Tagore had hoped many would start institutions like Sriniketan all over the country to bridge gaps between the underprivileged and the privileged. People like Satyarthi are doing amazing work in today’s context, but more like him are needed in our world.

We have more writings than I could mention here, and each is chosen with much care. Please do pause by our contents page and take a look. Much effort has gone into creating a space for you to relish different perspectives that congeal in our journal, a space for all of you. For this, we have the team at Borderless to thank– without their participation, the journal would not be as it is. Sohana Manzoor with her vibrant artwork gives the finishing touch to each of our monthly issues. And lastly, I cannot but express my gratefulness to our contributors and readers for continuing to be with us through our journey. Heartfelt thanks to all of you.

Have a wonderful festive season!

Best wishes,

Mitali Chakravarty

[1] Wild long grass

.

.

Visit the October edition’s content page by clicking here

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.