Keith Lyons in conversation with Lya Badgley

Lya Badgley’s life reads like an exotic adventure book you can’t put down, but she writes plot-driven suspense about women overcoming life-changing odds, against a backdrop of global conflict. In this interview, she shares her views about creativity, courage, persistence and resilience.

You’ve had an interesting life – how often do people say that to you? How do you tell the story of your life in a short elevator pitch?

I’ve been very lucky to have had choices – many do not. That said, being born in Myanmar to Montana parents, was a good start. From Seattle’s arts scene to documenting war crimes in Cambodia and opening a restaurant in Yangon, my life experiences fuel my creativity. I’ve been a mother, a former city council member, and an environmental activist and now write novels drawing deeply from my lived experiences.

So, you were born in Yangon, Myanmar. How did your parents from the Rocky Mountains come to be in Burma? What are your first memories from there?

My parents discovered the wider world when my father was stationed in northern Japan during the Korean War. They fell in love with Asia, and he went on to dedicate his life to academia, earning a doctorate in political science. They first arrived in Burma (Myanmar) in the late 1950s. One of my earliest memories is coming home from kindergarten in up-country Burma and telling my mother that all the children spoke English in class. Astonished, she accompanied me to school the next day, only to find that the children were speaking Burmese. I had simply assumed it was English. To this day, I love languages.

What kind of environment did your parents create which encouraged your creativity?

My mother was a true artist, always encouraging me to find beauty in everything around me. My father sparked a deep curiosity about the world, especially about the lives of everyday people. Our dinner table conversations were always lively, full of challenges and excitement, fueling my imagination and intellect. I was never allowed to leave the table without sharing something interesting and eating all my vegetables.

In 1987 what changed your life? How does Multiple Sclerosis affect you today?

In 1987, I developed a persistent headache that wouldn’t go away. Within two weeks, I lost vision in one eye. The diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis came swiftly. I’ll never forget the mix of terror and wonder as I looked at the pointillistic MRI image of my brain, and the doctor casually said, “Yep, see those spots? That’s definitely MS,” as if he were ordering lunch. Strangely, that diagnosis liberated me—after all, what’s the worst that could happen? Now, as I age, the disease may slow my body, but it hasn’t dimmed my spark.

In what ways has being a musician/poet/writer/artist been a struggle and challenge? Do you think that is part of process and it in turn fosters innovation?

The struggles of being an artist—whether overcoming rejection, creative blocks, or balancing art with daily life—are definitely part of the journey. But there’s also magic in that process. There’s something almost alchemical about wrestling with a challenge and, through that tension, creating something entirely new. It’s in those moments of uncertainty that the most unexpected ideas emerge, as if they’re waiting for the right spark. The struggle doesn’t just foster creativity—it transforms it, turning obstacles into opportunities. And the joy comes from watching that magic unfold, as your vision takes on a life of its own.

When did you return to Southeast Asia, and how did you come to work as a videographer on a clandestine expedition interviewing Burmese insurgents, and later helping document the genocide cases in Cambodia?

The short answer is — a boyfriend! In the early ’90s, I returned to Southeast Asia, driven by a deep connection to the region and feeling uncertain about what to do next after a failed marriage. Through a friend I met during Burmese language studies, I stumbled upon an unexpected opportunity to work as a videographer on a covert mission, documenting interviews with Burmese insurgents. That intense experience then led to my role in Cambodia, where I worked with Cornell University’s Archival Project. There, I helped microfilm documents from the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide, preserving crucial evidence that would later hold war criminals accountable. Both experiences were life-changing and cemented my passion for telling these vital stories.

You were among the few foreigners to open businesses in Burma in the 1990s. What hurdles were there to opening the 50th Street Bar & Grill Restaurant in Yangon, Myanmar? How was Burma at that time?

Opening the 50th Street Bar & Grill in Yangon in the mid ’90s was a real adventure, and I take great pride in being part of the first foreign-owned project of its kind at that time. Myanmar was just emerging from decades of isolation, with very few foreigners and even fewer foreign businesses. Navigating the bureaucracy was incredibly challenging — layers of red tape, and we often had to rely on outdated laws from the British colonial era just to get things moving. It took persistence, creative problem-solving, and a lot of patience. I had the advantage of understanding the culture and speaking a bit of the language, and I never worked through a proxy. I handled even the most mundane tasks myself—like sitting for hours in a stifling hot bank, waiting to meet the manager, who was hiding in the bathroom to avoid me!

Basic infrastructure issues like inconsistent electricity and unreliable suppliers were ongoing challenges. But despite all the hurdles, Yangon had a special energy then. The people were incredibly warm and resilient, and there was a palpable sense that the country was on the cusp of major change, even though it remained under military rule. Looking back, I’m proud to have been part of something so groundbreaking during such a unique moment in Myanmar’s history. It’s heartbreaking to see the return of darker times.

When did you first start writing and what has kept you writing?

In the ’80s, I began writing song lyrics for my music, which eventually evolved into poetry. It turned out I had more to say, and my word count steadily grew from there. I write because I have no choice; it’s an essential part of who I am.

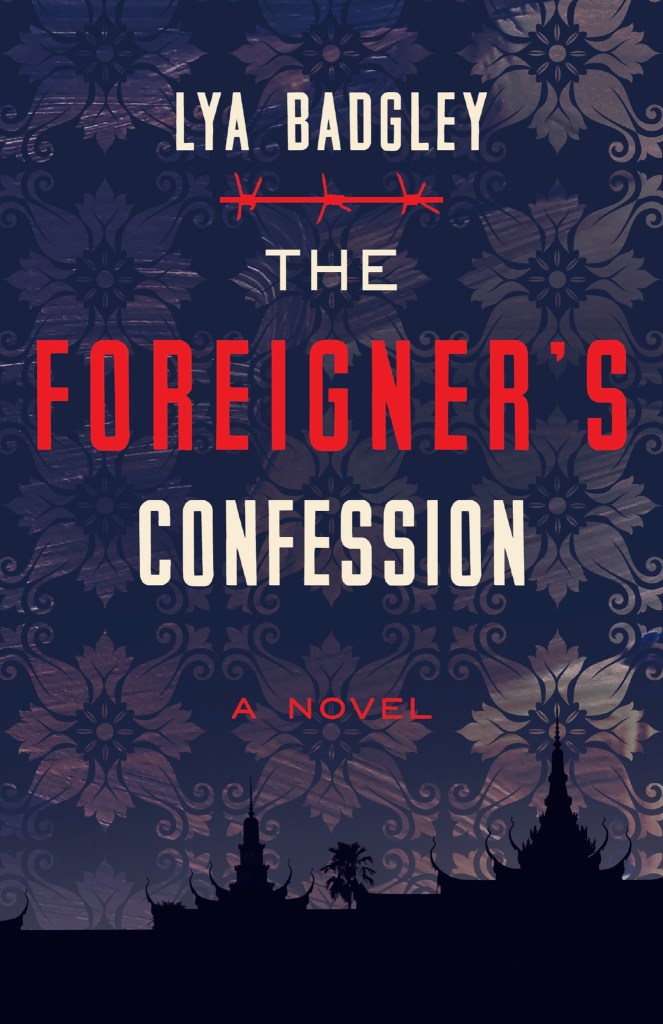

Your first novel, The Foreigner’s Confession, out in 2022, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, weaves together one person’s story and a country’s painful history. How do you integrate in the legacy of the past, a personal journey, a war-torn country and the themes of loss and regret?

In The Foreigner’s Confession, I explore the interconnectedness of personal stories and a nation’s history. I like using conflict zones as backdrops for my protagonist’s inner turmoil. These settings highlight the psychological landscape shaped by war and trauma, reflecting the chaos within the character. I’m fascinated by the notion that evil exists in each of us, and under the right circumstances, we’re all capable of bad things. This theme resonates throughout the narrative, as the characters grapple with their moral choices amidst the turmoil surrounding them. As Tom Waits[1] beautifully puts it, “I like beautiful melodies telling me terrible things” — that juxtaposition is central to my writing, illustrating how beauty and darkness can coexist and inform our understanding of the human experience.

When it comes to writing are you a planner or a pantser? What’s your process for writing, particularly when you want to bring in the setting, the history of a place, and authenticity?

I’m a pantser all the way! Just saying the word “spreadsheet” makes me break into a sweat. I wish I could create meticulous diagrams and beautiful whiteboards filled with colorful, fluttering sticky notes, but that just isn’t my style. For me, the story unfolds as I write. I refer to myself as a discovery writer. It’s a slow and sometimes tedious process but discovering what I didn’t know was going to happen is truly amazing. I draw from my personal experiences to provide authenticity.

Does writing suspense/mystery help make a novel more compelling because it has to be well-crafted and cleverly constructed?

I write the story buzzing in my brain and then try to determine the genre.

What do you think about the power and potential of a novel to reach readers in a different way, for example as a vehicle to give insight into the situation in Cambodia or Myanmar, the wider/deeper issues (like geopolitics/colonialism), and the present reflecting a troubled past?

Yes, yes, yes! Novels have the potential to foster empathy and understanding, challenging readers to confront uncomfortable truths. Can we humans please stop being so stupid? It’s doubtful, but we can only hope.

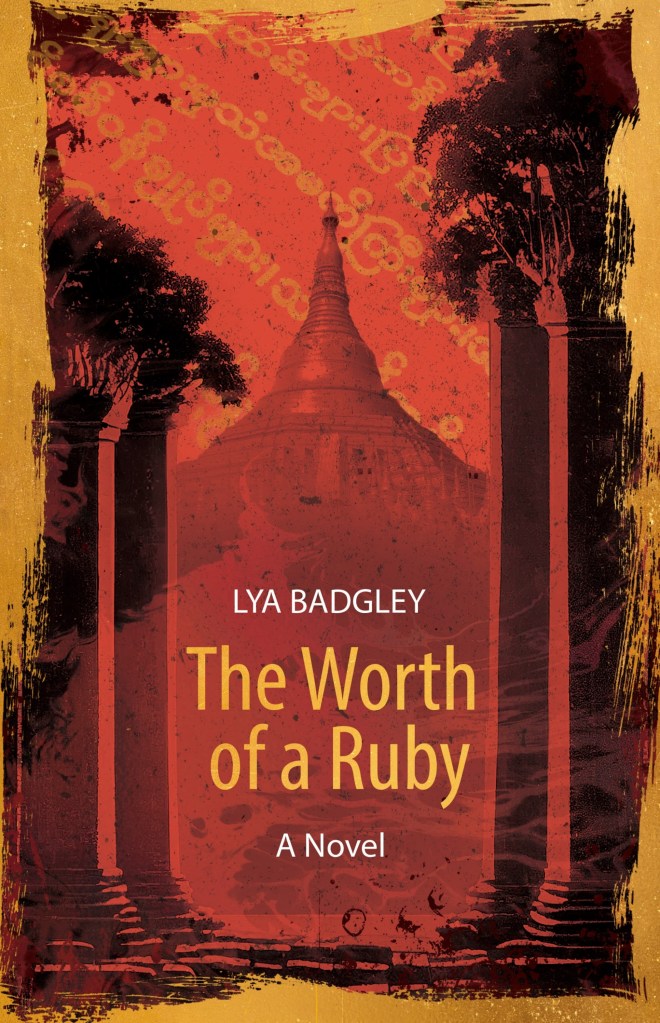

Last year your second novel, The Worth of a Ruby, was launched, and you’ve recently been in Myanmar. What’s been your impression of the place in 2024, still suffering under the coup and with not such good prospects as in the 2010s? Could you ever go back there to live?

Sitting in the Inya Lake Hotel in Yangon as I write this, I can see that the people here carry a veil over their eyes that I don’t recall from my previous visits. Nevertheless, the cyclical nature of oppression has persisted here for a long time. My husband and I would move back in a heartbeat if there were opportunities and adequate healthcare for my situation. This country remains a part of my identity, and I dream of a future where I can return to help contribute to its recovery.

Your current/recent visit to SE Asia has taken you to what places? What have been the most memorable experiences?

I’m in Yangon until mid-October and will then spend a few days in Singapore, slogging my books to the shops there. As always, the most memorable experiences are renewing the deep connections with the people I care about.

Both your books feature people/countries having to confront their past/dark side. How do you think a novel can help navigate through the complexities and nuances of situations, or at least show that nothing is as black and white as first thought?

That’s a complex question, and any answer can only touch the surface. Both of my novels explore people and countries grappling with their pasts and confronting their darker sides, but the truth is, no single story can fully capture the complexity of these situations. What a novel can do, however, is open a window into the nuances and shades of gray that exist beneath the surface. By diving into characters’ personal struggles and the layered histories of their countries, readers can begin to see that nothing is as black and white as it might seem. A novel helps illuminate the hidden motivations, moral ambiguities, and emotional complexities that are often overlooked, offering a more profound understanding of the tangled web of human experience.

Your work-in-progress novel is set in Bosnia. What themes will that explore?

The themes in my work-in-progress novel set in Bosnia will continue to explore the complexities of personal and national histories, much like my previous work. However, this time I’m weaving in elements of magic realism, drawing inspiration from the Sarajevo Haggadah and Balkan folktales. These mystical elements will add a new layer to the narrative, deepening the exploration of identity, memory, and the ways in which the past haunts the present. The use of folklore will allow me to delve into the region’s rich cultural traditions while keeping the focus on the enduring human themes of loss, resilience, and transformation.

Where is ‘home’ for you now? How do you think living in other countries has influenced your outlook and personality?

I am wildly curious, and home is the room I’m sitting in. Though we pay a mortgage on our condo in Snohomish, home has always been more about where I am in the moment than a fixed place. Living in different countries has profoundly shaped my outlook and personality. It’s given me a deep appreciation for diverse perspectives and a sense of adaptability. I’ve learned that people’s values and struggles can be both uniquely local and universally human. Experiencing different cultures has also sparked my curiosity and influenced the way I approach storytelling, allowing me to blend personal and global themes into my work.

What do you think are your points of difference/advantages that you bring to your writing?

One of the key differences I bring to my writing is my unique upbringing. Growing up in Myanmar with parents who encouraged both critical thinking and creativity gave me an early appreciation for the complexities of the world. I’ve lived in many countries and experienced firsthand the way cultures can both clash and blend, and that depth of perspective is something I try to infuse into my stories. Navigating a chronic disease like multiple sclerosis has also shaped my writing. It’s taught me resilience, patience, and how to find beauty in challenging situations. I think these experiences allow me to write characters and narratives that explore the shades of gray in life—the areas where pain, perseverance, and hope intersect.

Why do you think that a high proportion of expats/students/backpackers/digital nomads are from the Pacific Northwest and find themselves living and working in Southeast Asia? (I know three people from Snohomish who live in Asia).

It’s an interesting phenomenon, and I think the Pacific Northwest has some unique qualities that make it a breeding ground for wanderers. Growing up on the edge of the continent, facing west, there’s always been a sense of curiosity about what’s beyond the horizon. The region’s creative spirit—fueled by its music scene, constant rain, endless coffee, and a long history of innovation with computers and tech—fosters a mindset that’s open to exploration and new ideas. People from the PNW are used to thinking outside the box, and there’s a certain resilience that comes from enduring gray skies. This drive for adventure and discovery seems to naturally extend to places like Southeast Asia, where expats, students, backpackers, and digital nomads can experience a different pace of life while still tapping into their creative or entrepreneurial sides. Though, it blows my mind that you know three people from my little town of Snohomish living in Asia!

For aspiring writers and creatives, and for readers of Borderless, what’s your advice?

My advice for aspiring writers, creatives, and readers of Borderless is simple: always take the step, go through the door you don’t know. The unknown is where growth, creativity, and discovery happen. Don’t be afraid to embrace uncertainty and take risks in your work and life. Whether it’s starting a new project, exploring a different idea, or venturing into unfamiliar territory, those leaps often lead to the most rewarding experiences. Stay curious, keep pushing boundaries, and trust that the act of creating—no matter how daunting—will always teach you something new.

Where can readers find you?

Email: lyabadgley@comcast.net

Mobile: 360 348 7059

110 Cedar Ave, Unit 302, Snohomish WA 98290

www.facebook.com/lyabadgleyauthor

www.instagram.com/lyabadgleyauthor

Youtube: www.youtube.com/@lyabadgleyauthor

.

[1] American musician

Keith Lyons (keithlyons.net) is an award-winning writer and creative writing mentor originally from New Zealand who has spent a quarter of his existence living and working in Asia including southwest China, Myanmar and Bali. His Venn diagram of happiness features the aroma of freshly-roasted coffee, the negative ions of the natural world including moving water, and connecting with others in meaningful ways. A Contributing Editor on Borderless journal’s Editorial Board, his work has appeared in Borderless since its early days, and his writing featured in the anthology Monalisa No Longer Smiles.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International