‘Victory to Man, the newborn, the ever-living.’

They kneel down, the king and the beggar, the saint and

the sinner,

the wise and the fool, and cry:

‘Victory to Man, the newborn, the ever-living.’

— ‘The Child’ by Rabindranath Tagore1, written in English in 1930

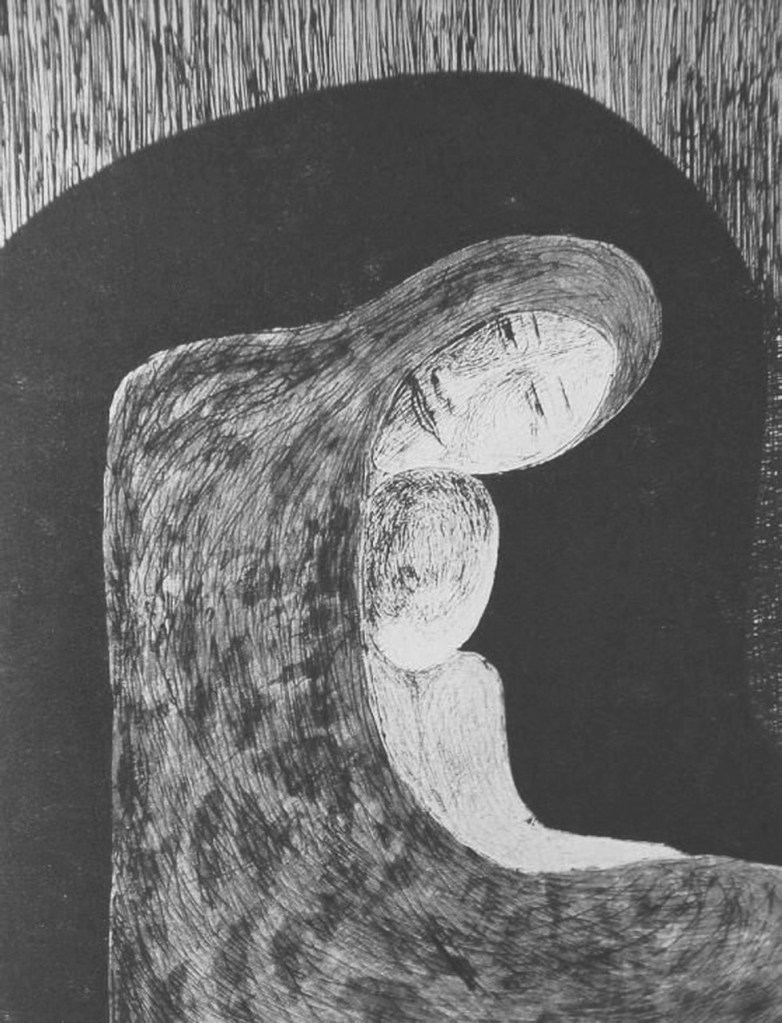

This is the month— the last of a conflict-ridden year— when we celebrate the birth of a messiah who spoke of divine love, kindness, forgiveness and values that make for a better world. The child, Jesus, has even been celebrated by Tagore in one of his rarer poems in English. While we all gather amidst our loved ones to celebrate the joy generated by the divine birth, perhaps, we will pause to shed a tear over the children who lost their lives in wars this year. Reportedly, it’s a larger number than ever before. And the wars don’t end. Nor the killing. Children who survive in war-torn zones lose their homes or families or both. For all the countries at war, refugees escape to look for refuge in lands that are often hostile to foreigners. And yet, this is the season of loving and giving, of helping one’s neighbours, of sharing goodwill, love and peace. On Christmas this year, will the wars cease? Will there be a respite from bombardments and annihilation?

We dedicate this bumper year-end issue to children around the world. We start with special tributes to love and peace with an excerpt from Tagore’s long poem, ‘The Child‘, written originally in English in 1930 and a rendition of the life of the philosopher and change-maker, Vivekananda, by none other than well-known historical fiction writer, Aruna Chakravarti. The poem has been excerpted from Indian Christmas: Essays, Memoirs, Hymns, an anthology edited by Jerry Pinto and Madhulika Liddle, a book that has been reviewed by Somdatta Mandal and praised for its portrayal of the myriad colours and flavours of Christmas in India. Christ suffered for the sins of humankind and then was resurrected, goes the legend. Healing is a part of our humanness. Suffering and healing from trauma has been brought to the fore by Christopher Marks’ perspective on Veronica Eley’s The Blue Dragonfly: healing through poetry. Basudhara Roy has also written about healing in her take of Kuhu Joshi’s My Body Didn’t Come Before Me. Bhaskar Parichha has reviewed a book that talks of healing a larger issue — the crises that humanity is facing now, Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World, by ex-British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, Nobel Laureate Michael Spence, Mohamed El-Erian and Reid Lidow. Parichha tells us that it suggests solutions to resolve the chaos the world is facing — perhaps a book that the world leadership would do well to read. After all, the authors are of their ilk! Our book excerpts from Dr Ratna Magotra’s Whispers of the Heart – Not Just A Surgeon: An Autobiography and Manjima Misra’s The Ocean is Her Title are tinged with healing and growth too, though in a different sense.

The theme of the need for acceptance, love and synchronicity flows into our conversations with Afsar Mohammad, who has recently authored Remaking History: 1948 Police Action and the Muslims of Hyderabad. He shows us that Hyderabadi tehzeeb or culture ascends the narrow bounds set by caged concepts of faith and nationalism, reaffirming his premise with voices of common people through extensive interviews. In search of a better world, Meenakshi Malhotra talks to us about how feminism in its recent manifestation includes masculinities and gender studies while discussing The Gendered Body: Negotiation, Resistance, Struggle, edited by her, Krishna Menon and Rachana Johri. Here too, one sees a trend to blend academia with non-academic writers to bring focus on the commonalities of suffering and healing while transcending national boundaries to cover more of South Asia.

That like Hyderabadi tehzeeb, Bengali culture in the times of Tagore and Nazrul dwelled in commonality of lore is brought to the fore when in response to the Nobel laureate’s futuristic ‘1400 Saal’ (‘The year 1993’), his younger friend responds with a poem that bears not only the same title but acknowledges the older man as an “emperor” among versifiers. Professor Fakrul Alam has not only translated Nazrul’s response, named ‘1400 Saal’ aswell, but also brought to us the voice of another modern poet, Quazi Johirul Islam. We have a self-translation of a poem by Ihlwha Choi from Korean and a short story by S Ramakrishnan in Tamil translated by T Santhanam.

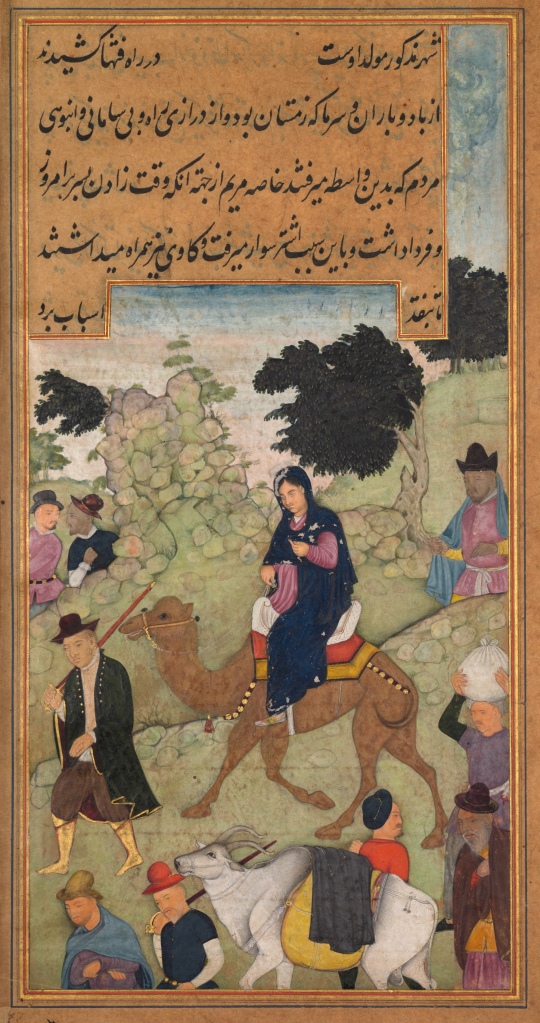

Our short stories travel with migrant lore by Farouk Gulsara to Malaysia, from UK to Thailand with Paul Mirabile while chasing an errant son into the mysterious reaches of wilderness, with Neeman Sobhan to Rome, UK and Bangladesh, reflecting on the Birangonas (rape victims) of the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation war, an issue that has been taken up in Malhotra’s book too. Sobhan’s story is set against the backdrop of a war which was fought against linguistic hegemony and from which we see victims heal. Sohana Manzoor this time has not only given us fabulous artwork but also a fantasy hovering between light and dark, life and death — an imaginative fiction that makes a compelling read and questions the concept of paradise, a construct that perhaps needs to be found on Earth, rather than after death.

The unusual paradigms of life and choices made by all of us is brought into play in an interesting non-fiction by Nitya Amlean, a young Sri Lankan who lives in UK. We travel to Kyoto with Suzanne Kamata, to Beijing with Keith Lyons, to Wayanad with Mohul Bhowmick and to Langkawi with Ravi Shankar. Wendy Jones Nakanishi argues in favour of borders with benevolent leadership. Tongue-in-cheek humour is exuded by Devraj Singh Kalsi as he writes of his attempts at using visiting cards as it is by Rhys Hughes in his exploration of the truth about the origins of the creature called Humpty Dumpty of nursery rhyme fame.

Poetry again has humour from Hughes. A migrant himself, Jee Leong Koh, brings in migrant stories from Singaporeans in US. We have poems of myriad colours from Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Patricia Walsh, John Grey, Kumar Bhatt, Ron Pickett, Prithvijeet Sinha, Sutputra Radheye, George Freek and many more. Papia Sengupta ends her poem with lines that look for laughter among children and a ‘life without borders’ drawn by human constructs in contrast to Jones Nakanishi’s need for walls with sound leadership. The conversation and dialogues continue as we look for a way forward, perhaps with Gordon Brown’s visionary book or with Tagore’s world view of lighting the inner flame in each human. We can hope that a way will be found. Is it that tough to influence the world using words? We can wish — may there be no need for any more Greta Thunbergs to rise in protest for a world fragmented and destroyed by greed and lack of vision. We hope for peace and love that will create a better world for our children.

As usual, we have more content than mentioned here. All our pieces can be accessed on the contents’ page. Do pause by and take a look. This bumper issue would not have been possible without the contribution of all the writers and our fabulous team from Borderless. Huge thanks to them all and to our wonderful readers who continue to encourage us with their comments and input.

Here’s wishing you all wonderful new adventures in the New Year that will be born as this month ends!

Mitali Chakravarty

- Indian Christmas: Essays, Memoirs, Hymns edited by Jerry Pinto & Madhulika Liddle ↩︎

Click here to access the content’s page for the December 2023 issue

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.