By Lopamudra Nayak

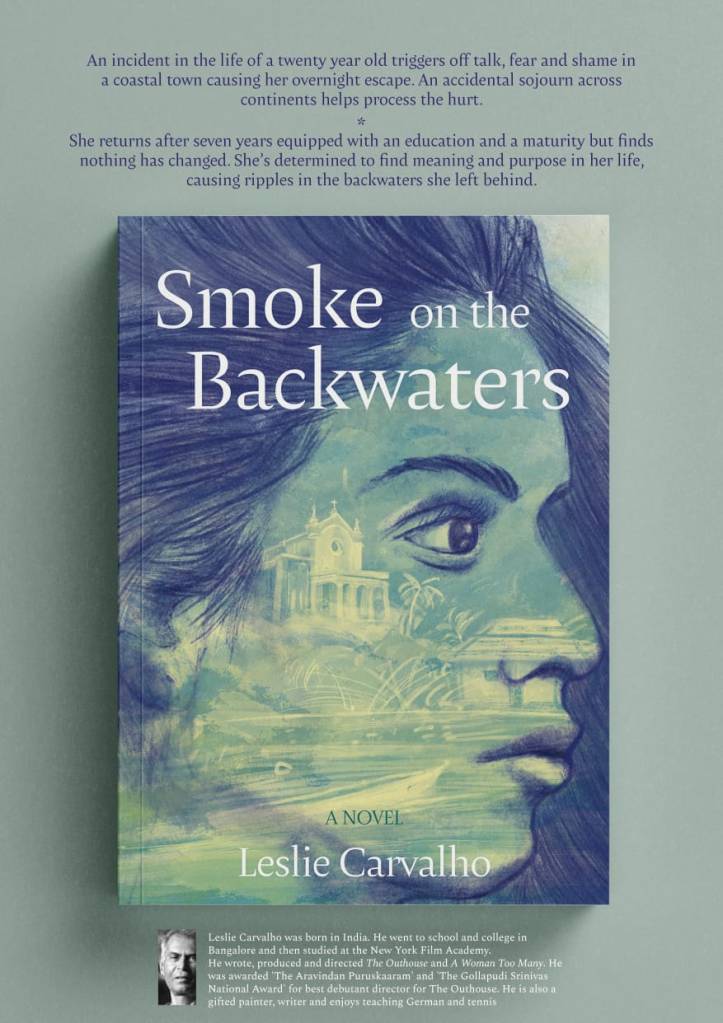

In 2015, Shashi Tharoor’s speech at the Oxford Union exploded across social media, striking a chord far beyond academic or diplomatic circles. Framed around the motion “This House Believes Britain Owes Reparations to Her Former Colonies”, Tharoor—alongside eloquent speakers from Ghana and Jamaica—argued persuasively for moral accountability from the former empire. Tharoor’s speech was widely appreciated in India because of the succinctness with which he illustrated how and why colonial rule exploited the subcontinent, and how violence and racism were the order of those days.

“It’s a bit rich to oppress, enslave, kill, torture, maim people for 200 years and then celebrate the fact that they are democratic at the end of it. We were denied democracy, so we had to snatch it, seize it from you,” he said to loud applause from the audience.

But while insightful points such as these formed the crux of Tharoor’s eloquent speech, it was his rapier barbs that had the esteemed audience (and netizens alike) crowing. “No wonder that the sun never set on the British Empire,” he says at one point, referencing a common boast used to illustrate the sheer extent of Britain’s power, “because even God couldn’t trust the English in the dark.”

The speech’s viral success revealed a yearning—particularly among millennials raised on televised debates and editorials—for a mode of discourse that is rapidly disappearing. Where once prime-time slots featured fiery discussions on social and political issues about caste, class, gender, and policy, today’s digital platforms prioritise speed, relatability, and aesthetics.

In the India of today, a viral tweet can spark more conversation than a peer-reviewed article. A beauty influencer’s “Get Ready With Me” vlog is more likely to trend than a lecture by a scholar on social justice. The thought leaders of the past were expected to speak with gravity; the content creators of the present are expected to sparkle. When public intellectuals are replaced by public influencers, the nature of cultural discourse changes. Popular culture, once a mirror held up to society, now leans into escapism. Complex socio-political debates are flattened into clickable soundbites, and intellectual inquiry is often sidelined by algorithm-friendly content categories, sorted by SEO value[1].

Intellectuals once forced us to think harder, ask more difficult questions, live with complexity. Influencers invite us to feel seen, validated, or soothed. One expands the self, the other simply flatters it.

India’s Golden Age of Thought: When Public Intellectuals Shaped the Nation’s Conscience

Once upon a time, India did not lack public intellectuals. In fact, the early decades after Independence saw them thrive because India’s tradition of intellectual dissent is long and storied. Figures like Nehru, Gandhi, Ambedkar, Tagore—they were not just leaders or writers; they were public philosophers.

Thinkers engaged with the moral and political questions of their time, not just within academia but in public forums, books, interviews, op-eds, and essays that reached a wide, engaged readership. They helped build the intellectual spine of a newly independent nation grappling with secularism, caste, democracy, and justice.

Even in Bollywood, cinema once offered social critique—from Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (Thirsty, 1957) to Shyam Benegal’s Ankur (The Seedling, 1974). They were conscience-keepers, cultural critics, and truth-speakers. They didn’t shy away from controversy—many actively courted it. They weren’t afraid to speak against majoritarianism, economic inequality, censorship, or communalism.

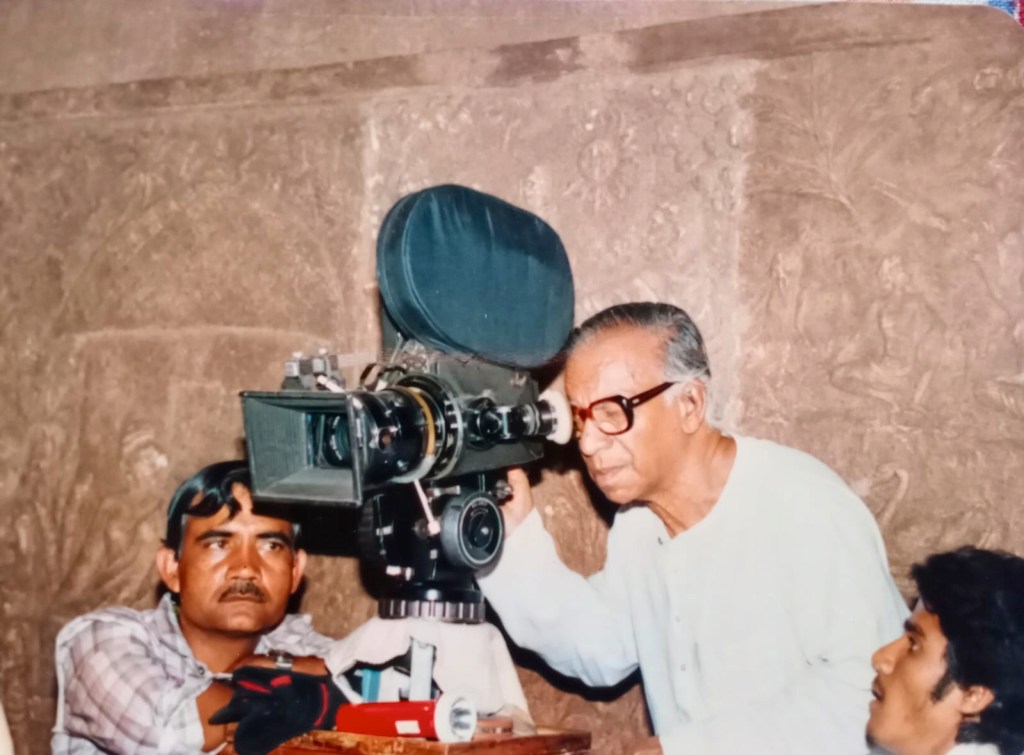

Meanwhile, halfway across the world in Texas, a young boy named Wes Anderson—who would go on to become one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary cinema—found himself deeply influenced by Satyajit Ray. It wasn’t just Ray’s pioneering cinematic style that captivated him, but also his prolific work as a writer and illustrator, and his powerful engagement with public discourse. Through his films, Ray offered a radical and empathetic lens on Indian society, boldly confronting issues such as poverty, gender roles, the tension between tradition and modernity, and the human consequences of social change—perspectives that were remarkably ahead of their time and continue to resonate across cultures.

Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam was one of modern India’s most beloved and influential public intellectuals—a scientist, teacher, and former President who embodied the rare blend of deep technical knowledge and visionary humanism. Revered as the “Missile Man of India” for his pivotal role in advancing the country’s space and defence programs, Kalam also brought science into the public imagination with clarity, humility, and hope. His presidency (2002–2007) was marked by an earnest outreach to young people, whom he inspired to dream beyond the limitations of circumstance. Unlike many in power, Kalam believed in the democratisation of knowledge—he made complex ideas accessible, challenged youth to innovate, and constantly linked progress with ethics and spirituality. In doing so, he redefined what it meant to be a public intellectual in India: not someone cloistered in academia, but a leader who imagined a better future and invited the nation to build it with him.

Brains Behind Paywalls: How Intellectualism Lost Its Spotlight

There’s no shortage of brilliant minds today—but intellectualism requires both platform and patience. Neither is abundant. A YouTuber dissecting colonial legacy in Indian education may get a few thousand views; a beauty blogger with “chai latte skin” content racks up millions. But now, intellectuals are trapped producing work for journals and conferences rather than the public sphere. As a result, public-centred intellectualism has become rare. It’s not because intellectuals of that caliber no longer exist, but that the structures that once made their ideas visible have been buried under layers of institutional gatekeeping.

The decline of the public intellectual isn’t just the result of a shifting media landscape—it’s also tied to how our access to and expectations around knowledge have evolved. There was a time when intellectuals were celebrated as generalists, able to navigate literature, politics, science, and philosophy, and translate complex ideas for a broader audience. Think of Susan Sontag or Bertrand Russell—figures who didn’t confine themselves to narrow academic lanes but moved fluidly across disciplines to spark public thought and dialogue.

Today, intellectual life has become increasingly siloed. Hyper-specialization has turned academia into an insular world where scholars speak primarily to other scholars. Rather than bridging the gap between advanced knowledge and public discourse, modern academics are often locked within their own echo chambers. The public philosopher who once commented on culture and politics has given way to specialists producing work for a niche audience of peers.

Even when academics do attempt to reach beyond their field, they’re often met with suspicion. A historian writing on political theory or a physicist reflecting on metaphysics is likely to be dismissed for stepping outside their “expertise.” Intellectual authority today is rigidly policed, and interdisciplinarity—once a hallmark of great thinkers—is now treated with skepticism.

From Public Intellectuals to Public Aestheticism: How Influence Got a Makeover

Today’s cultural powerhouses operate on a very different wavelength than their predecessors. Where figures like Susan Sontag or James Baldwin once shaped public consciousness through sharp intellect and critical writing, today’s influencers—like Kim Kardashian—wield their power almost entirely through aesthetics. Kardashian doesn’t publish essays; she sets the tone for global beauty trends. With each new look—glazed donut skin, brownie lips, strawberry makeup, and the almost comically indulgent cinnamon cookie butter hair—the Kardashians and Jenners reshape beauty norms with a force that rivals traditional intellectuals.

In India, the landscape mirrors this shift. Influencers like Ananya Panday and Ranveer Allahbadia amass millions of views despite offering little in terms of originality or eloquence. Much of their content borrows from what’s already been done, often repackaged with no clear voice of their own. Unlike cultural figures such as Shabana Azmi or even Priyanka Chopra[2]—whose words once commanded attention and mattered—many of today’s digital celebrities struggle when pulled out of the comfort zone of scripted, bite-sized platforms. Their polished online personas crumble under the pressure of unscripted public discourse.

What we’re left with is a curated illusion, a constant performance of identity. And the troubling part? Young audiences are watching, emulating, and internalising these facades—until, inevitably, a scandal breaks the spell. In an era ruled by surface and spectacle, authenticity has become the rarest currency of all.

If Joan Didion or Arundhati Roy represented a time when public intellectualism had mass appeal, these influencers represent what has replaced it: public aestheticism. A philosopher might spend years constructing a critique on our society, but an influencer can change peoples’ worldviews with a single Instagram post. Influence now moves at the speed of an Instagram story. The philosopher builds theory; the influencer sells a mood. In this new aesthetic economy, they are the message, the medium, and the marketplace all at once. This is not an incidental shift, but a reflection of our broader cultural transformation.

Although, this is absolutely not a wholesale condemnation of influencers. Many use their platforms to raise awareness, fundraise, and spotlight important issues. But influence has become aestheticised. And when beauty, brevity, and branding become the dominant currencies of expression, difficult truths become harder to hear.

Even figures with a platform one would consider intellectual, like a podcast or blog, tend to operate within a different framework than the public intellectuals of the past. The most successful are the ones who know how to package their ideas into easily consumable formats. Their content may demand engagement, but not necessarily deeper thinking. The most successful cultural critics of our digital age are simply a different kind of influencer, one who may sell a worldview rather than a skincare routine, but are selling something nonetheless.

Amidst all of this, we have lost the expectation of being challenged by our cultural figures. We have lost the collective memory of what it means to gather around an idea rather than a trend. We have lost the stamina for long-form thinking. We now crave hot takes instead of deep dives, personality over principle, vibes over values. We’ve also stopped expecting our cultural figures to challenge us. We ask them to inspire us, to entertain us, to market their authenticity. We no longer crowd into halls for heated debates—we scroll.

When Influence Replaces Insight: The Rise of Apathy and the Fall of Public Thought

The culture hasn’t gone quiet though. Indian influencers—fashion bloggers, tech reviewers, lifestyle curators, “finance bros”, even comic creators—are the new cultural capital. They dominate conversations on what matters to people: from wedding aesthetics and productivity hacks to skincare routines and budget investments. The currency of their influence isn’t depth but relatability, not dissent but delight. Even in the realm of “education”, we find influencers gamifying complex financial or political ideas into simplified carousels or 60-second explainers. It’s not necessarily bad—but it is diluted.

It’s also understandable why many hesitate to enter intellectual spaces today—there’s a prevailing sense that everything worth saying has already been said. We live in an age where every thought seems pre-articulated, every argument countered, every counterpoint already dissected. The landscape isn’t lacking in intellectual potential; it’s that fewer people feel confident stepping into the role of a public intellectual, believing true originality is no longer possible.

This mindset breeds an intellectual echo chamber. Rather than contributing to the discourse, many settle into passive consumption, convinced that someone else has already voiced every worthwhile idea.

But the truth is, no conversation is ever truly finished. History shows us that ideas are living things—they shift, adapt, and deepen depending on who engages with them and when. The same philosophical questions that animated thinkers centuries ago continue to evolve, finding new relevance in each generation. Feminism as it was understood in the 1970s is not the feminism of today. Jean Baudrillard’s meditations on media and hyperreality in the 1980s feel hauntingly prescient in our digital age—but our reading of him is inevitably shaped by the world we now inhabit. Every era reinterprets the past, and every new voice brings a fresh lens. That’s what keeps the intellectual tradition alive.

Reclaiming Thought: Can Intellectualism Survive the Age of Spectacle?

So, can the intellectual space be reclaimed, or has it been permanently absorbed into digital spectacle? Long-form discussions found in podcasts, essays, and forums are a great starting point. Platforms of these media types allow for deeper exploration of ideas, where nuance and depth are greatly valued.

And it’s not that intellectuals have disappeared. They are still here, writing essays, protesting laws, mentoring students. But they’ve been pushed to the peripheries of public attention. Their audiences are shrinking, and their words are often drowned out by the louder, shinier pull of influencer content.

But intellectual spaces aren’t only limited to these traditional platforms. Niche online communities like internet book clubs on Fable or Instagram create new ways for people to connect with unique ideas. You can also incorporate intellectual conversation into your everyday life. Attend local events, art galleries, or even start casual discussions among friends to make these topics more accessible and relevant. The intellectual sphere may have shifted, but it isn’t gone. We simply have to work to reclaim these spaces with people who are willing to engage deeply with ideas.

Ultimately, the death of the public intellectual may not be as tragic as it seems, it may just mean that intellectualism is taking on new forms. But we have to ensure we’re not losing sight of what really matters—the depth, complexity, and refusal to settle for easy answers in the pursuit of something greater.

Culture Is Still Loud—It Just Doesn’t Want to Make You Uncomfortable Anymore

There’s another reality unique to India: the active suppression of dissent. To be an intellectual in India today, particularly one critical of the status quo, is to court danger. Writers have been jailed (Anand Teltumbde), journalists have been shot (Gauri Lankesh), and students have been arrested for protest slogans. In such an atmosphere, who would choose to be a public intellectual?

The public intellectual, by definition, is someone who speaks truth to power. In India, speaking truth to power comes at a high cost. And so, instead, we scroll. Meanwhile, the influencer class thrives because they are apolitical by design. Their influence is rooted in apathy, in not asking uncomfortable questions. This is not a coincidence. It is by systemic design. The less we think, the more we consume. The more aestheticised our discontent, the less threatening it becomes. Influencers now perform the soft work of culture—sedating, distracting, pacifying—while hard truths are hidden behind paywalls, FIRs, and broken institutions.

But if the public intellectual is to make a comeback, we as an audience must do our part. We have to choose depth over dopamine, discomfort over convenience. We must resist the temptation to aestheticise every idea until it’s just another lifestyle choice.

Because when thought leaders become brand ambassadors, and reflection becomes a trend, we risk forgetting that ideas—not images—are what truly shape society.

The public intellectual may be on life support, but the conversation isn’t over. It never is.

[1] SEO (Search Engine Optimisation) value refers to the estimated monetary worth of organic traffic generated by a website through search engine optimisation efforts.

[2] Actresses

Lopamudra Nayak is a poet, freelance writer, and biotechnologist with a passion for literature and storytelling. She writes poetry, book reviews, and reflections on pop culture on her blog, Substack and Instagram.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International