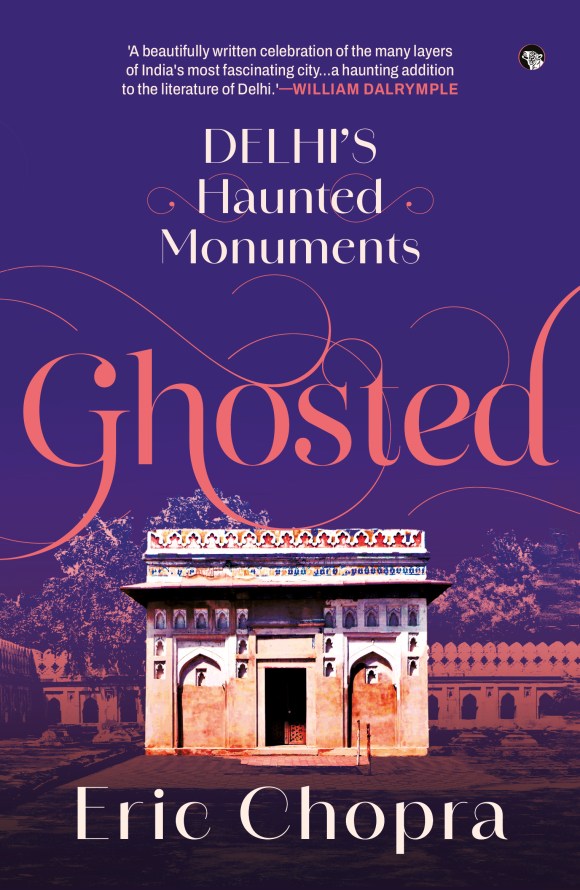

Title: Ghosted: Delhi’s Haunted Monuments

Author: Eric Chopra

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

JAMALI-KAMALI

Menacing Jinn and Forbidden Pasts

Do people who come here ask you about the jinn?’ My question lingered in the air for a bit. I was in the courtyard of a medieval mosque. At nightfall, this monument is entrancing, with its white marble dazzling against the red sandstone and the medallions on the spandrels of its pishtaq (arched entrance) appearing as glaring white eyes.

‘That’s all they mostly ask…’ said the guard as he began to dig through his pockets, looking for a key upon my request. ‘But I have my guru’s blessings, nobody has harmed me! And see this, that very guru allows me to find everything.’ He triumphantly raised his hands and dangled the keys which would open the perpetually locked gate of the graveyard that hosts the supposedly ‘haunted’ tomb adjacent to the mosque.

I remember how strong the scent of the devil’s tree, Saptaparni, was that evening. This is the fragrance of October in Delhi, playing its part as the harbinger of winter. The intensity of the aroma was unsurprising since I was surrounded by trees as I made my way through the Mehrauli Archaeological Park. The moon was aglow, and so was the Qutb Minar, (Fig. 23) India’s tallest minaret that oversees this part of the city like a powerful ancestral force.

There have been times aplenty when I have been warned to not come to this park after sunset, not only because of its forested environs but also for the unseeable forces who are believed to inhabit it. ‘At least tie your hair…’ I am told by the flower-sellers who sit in rows across the narrow road outside one of the entrances to the park. My hair, if left untied, is an invitation for the menacing jinn to follow me, and not only that, they would also leave an imprint across my cheeks: ‘Beware…they will slap you!’

Jinn are ‘intermediary’ and complex beings who are made of smokeless fire, unlike humans, who are made of clay. In Islam, both humans and jinn are subject to the Revealed Law and will be held accountable for their actions on the Day of Judgement. Like humans, jinn are considered ‘responsible beings’ as they possess the freedom to choose how they lead their lives. However, they also have unique characteristics: shape-shifters, invisible entities, and magical trickery. While the jinn do possess these abilities, their power serves as a test, and they will face consequences if they misuse it to terrorise people.

But it is not that these jinn float and reside in the many niches that this historical park is dotted with. There is a particular place where they have found refuge, at the tomb and mosque of Jamali Kamboh—a Sufi, courtier, poet, emissary, and globe-trotter. But if you ever find yourself in Mehrauli and ask anyone about him, you would never hear his name being taken alone. It is always in companionship with Kamali, the identity that local lore has given to the mystery man that Jamali is buried next to.

Together, Jamali-Kamali are found in a single-storied mausoleum as magnificent as the meaning behind Jamali’s name: the one who inspires beauty. Resembling a gem-box, it is even protected like one since special permission is required to see it from the inside, though legends will also have you believe that it must also be kept that way so as to not provoke the wrath of the jinn. The monument that is always accessible in this complex is the mosque, also built by Jamali, and to its north is where his tomb lies, in a cemetery surrounded by other open-air graves.

But on that October evening, my request to be let inside had been granted. As the guard reached the graveyard’s gate, the locks clinked and clanked, and I wondered how I would make a rather frustrating character in a horror movie, much like those who are aware of the consequences and yet become responsible for incurring the curse of the Mummy. But I didn’t have to dwell on this thought for too long for by then, the gate had been opened, and I marched purposefully towards Jamali-Kamali.

A chained wooden door shields this square tomb. To get a glimpse of the interiors, one has to walk to its northern and eastern sides which boast beautiful sandstone jalis (latticed window screens). To its north I went, lured by the devil tree’s scent marrying the aroma of the incense sticks that had been lined right under the screen. The guard told me that somebody had come earlier to the tomb to pray and had lit those sticks. ‘But even when there are no agarbattis here, I still always get a whiff of them,’ he said.

I peeked in through the screen and there they were in their shiny graves, right next to one another—Jamali and Kamali. They rest under a domed ceiling that gleams with magnificent motifs and its edges sing the verses of Jamali. It appears as if these two spend their afterlife at peace under an ornate galaxy of red, white, and blue.

Having beheld its magic, it was puzzling. How does something so precious come to attain the reputation as one of the city’s most haunted sites? But there were more questions. About its uniqueness: how does such a pioneering sixteenth-century tomb, spanning the period between the decline and rise of two dynastic epochs, find itself in Delhi’s first city? About its multiple identities: how can this monument be a place of horrors and simultaneously a haven of sanctity and an oasis for lost histories? And inevitably, about its enigma, not only due to the jinn, but also because of Kamali: who really was this man, sometimes seen as Jamali’s pupil, at other times his friend, and often, his lover?

It is through the untangling of these various threads which tie Jamali-Kamali together that we may reach closer to understanding what makes this place so astonishing. And thus, the story can only begin at one place…

(Extracted from Ghosted: Delhi’s Haunted Monuments by Eric Chopra. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2025)

About the Book

Delhi is haunted—by its ghosts, its ruins, and its unending capacity for rebirth. In the shadow of medieval mosques and Mughal tombs, the past refuses to stay buried. Saints, Sultans, poets, and lovers—all linger in the city’s imagination, their stories shaping how we remember what once was.

In Ghosted, historian and storyteller Eric Chopra journeys through the capital’s most beguiling sites—Jamali-Kamali, Firoz Shah Kotla, Khooni Darwaza, the Mutiny Memorial, and Malcha Mahal—to unearth a Delhi that exists between worlds: a palimpsest where Sufis bless kings, jinn listen to grievances, and begums occupy dilapidated hunting lodges. What begins as a search for Delhi’s haunted monuments becomes a meditation on why we are drawn to the dead and how ghost stories become vessels of collective memory.

Blending archival research with folklore, myth, and reflection, Chopra paints an intimate portrait of a city forever in dialogue with its former selves. Through invasions and rebirths, he reveals that Delhi’s spirit resides not just in its monuments but in the unseen presences that linger among them.

Ghosted is a lyrical, haunting journey through the city’s spectral landscape— an invitation to listen to what its echoes tell us about memory and identity.

About the Author

Eric Chopra is a public historian, writer, media creator, podcaster, and the founder of Itihāsology, an inclusive platform dedicated to Indian history and art. He leads a range of heritage experiences at museums and monuments and designs history-musicals in which he performs as a storyteller. Chopra is the co-host of the For Old Times’ Sake podcast and Jaipur Literature Festival’s Jaipur Bytes podcast. He also writes and curates for numerous festivals and events focused on history, literature, and the performing arts.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL