Most people like you and me connect with the commonality of felt emotions and needs. We feel hungry, happy, sad, loved or unloved and express a larger plethora of feelings through art, theatre, music, painting, photography and words… With these, we tend to connect. And yet, larger structures created over time to offer security and governance to the masses—of which you and I are a part — have grown divisive, and, by the looks of it, the fences nurtured over time seem insurmountable. To retain these structures that were meant to keep us safe, wars are being fought and many are getting killed, losing homes and going hungry. We showcase such stories, poems and non-fiction to create an awareness among those who are lucky enough to remain untouched. But is there a way out, so that all of us can live peacefully, without war, without hunger and with love and a vision towards surviving climate change which (like it or not) is upon us?

Creating an awareness of hunger and destruction wreaked by war is a heartrending story set in Gaza by JK Miller. While Snigdha Agrawal’s narrative gives a sense of hope, recounting a small kindness by a common person, Sayan Sarkar shares a more personal saga of friendship and disillusionment — where people have choice. But does war leave us a choice as it annihilates friendships, cities, homes and families? Naramsetti Umamaheswararao’s story reiterates the belief in the family – peace being an accepted unit. Vela Noble’s fantastical fiction and art comes like a respite– though there is a darker side to it — with a touch of fun. Perhaps, a bit of fantasy and humour opens the mind to deal with the more sombre notes of existence.

The translation section hosts a story by Hamiruddin Middya, who grew up as a farmer’s son in Bengal. Steeped in local colours, it has been rendered into English by V Ramaswamy. Nazrul’s song revelling in the colours of spring has been translated from Bengali by Professor Fakrul Alam. Atta Shad’s pensive Balochi lines have been brought to us in English by Fazal Baloch. Isa Kamari continues to bring the flavours of an older, more laid-back Singapore with translations of his own Malay poems. A couple of Persian verses have been rendered into English by the poet, Akram Yazdani, herself. Questing for harmony, Tagore’s translated poem while reflecting on a child’s life, urges us to have the courage to be like a child — open, innocent and willing to imagine a world laced with trust and hope. If we were all to do that, do you think we’d still have wars, violence and walls built on hate and intolerance?

While in a Tagorean universe, children are viewed as trusting and open, does that continue a reality in the current world that believes in keeping peace with weapons? Contemporary voices think otherwise. Manahil Tahir brings us a touching poem in a doll’s voice, a doll belonging to a child victimised by violence. While violence pollutes childhood, pollution in Delhi has been addressed by Goutam Roy in verse. Poignant lines from Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal make one question the idea of home and borders while Snehaprava Das has interpreted the word ‘borderless’ in her own way. We have more colours of humanity from Allan Lake, Chris Ringrose, Alpana, Lynn White, C.Mikal Oness, Shamim Akhtar, Jim Bellamy,John Swain, Mohul Bhowmick and SR Inciardi. Ryan Quinn Flanagan has given fun lines about a snow fight while Rhys Hughes has shared a humorous poem about a clumsy giant.

Bringing in humour in prose is Devraj Singh Kalsi’s musing about horoscopes! While, with a soupçon of irony Farouk Gulsara talks of his ‘holiday’, Meredith Stephen takes us to a yacht race in Australia and Mohul Bhowmick to Pondicherry. Gower Bhat writes of his passion for words while discussing his favourite books. Ratnottama Sengupta introduces us to contemporary artists from her part of the world.

Mario Fenech takes a look at the idea of time. Amir Zadnemat writes of how memory is impacted by both science and humanities while Andriy Nivchuk brings to us snippets from Herodotus’s and Pericles’s lives that still read relevant. Ravi Varmman K Kanniappan gives the journey of chickpeas across space and time, asserting: “The chickpea does not care about your ideology, your portfolio, or your meticulously curated identity. It will grow, fix nitrogen, feed someone, and move on without a press release.” It has survived over aeons in a borderless state!

In book excerpts, we have a book that transcends borders as it’s a translation from Assamese by Ranjita Biswas of Arupa Kalita Patangia’s Moonlight Saga. Any translation is an attempt to integrate the margins into the mainstream of literature, and this is no less. The other excerpt is from Natalie Turner’s The Red Silk Dress. Keith Lyons has interviewed Turner about her novel which crosses multiple cultures too while on a personal quest.

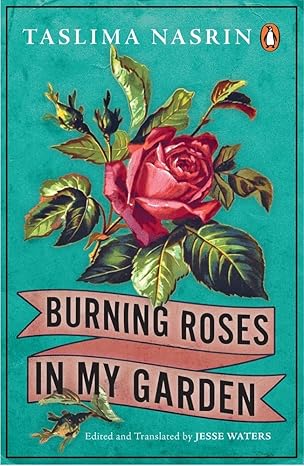

In reviews, Somdatta Mandal discusses a book that explores the colours of a river across three sets of borders, Sanjoy Hazarika’s River Traveller: Journeys on the TSANGO-BRAHMAPUTRA from Tibet to the Bay of Bengal. Rakhi Dalal writes about a narrative centring around migrants, Sujit Saraf’s Every Room Has a View — A Novel. Anindita Basak reviews Taslima Nasrin’s poetry, Burning Roses in my Garden, translated from Bengali by Jesse Waters. Bhaskar Parichha reviews Kailash Satyarthi’s Karuna: The Power of Compassion. In it, Satyarthi suggest the creation of CQ — Compassion Quotient— like IQ and EQ, claiming it will improve our quality of life. What a wonderful thought!

Could we be yearning compassion?

Holding on to that idea, we invite you to savour the contents of our February issue.

Huge thanks to all our contributors and readers for making this issue possible. Heartfelt thanks to our wonderful team, especially Sohana Manzoor for her fabulous artwork.

Enjoy the reads!

Let’s look forward to the spring… May it bring new ideas to help us all move towards more amicable times.

Mitali Chakravarty

CLICK HERE TO ACCESS THE CONTENTS FOR THE FEBRUARY 2026 ISSUE.

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.