A conversation with Neeman Sobhan

Neeman Sobhan, born in the West Pakistan of Pre-1971, continues a citizen of both her cultural home, Bangladesh, and her adopted home, Italy. Her journey took her to US for five years but the majority of times she has lived in Italy – from 1978. What does that make her?

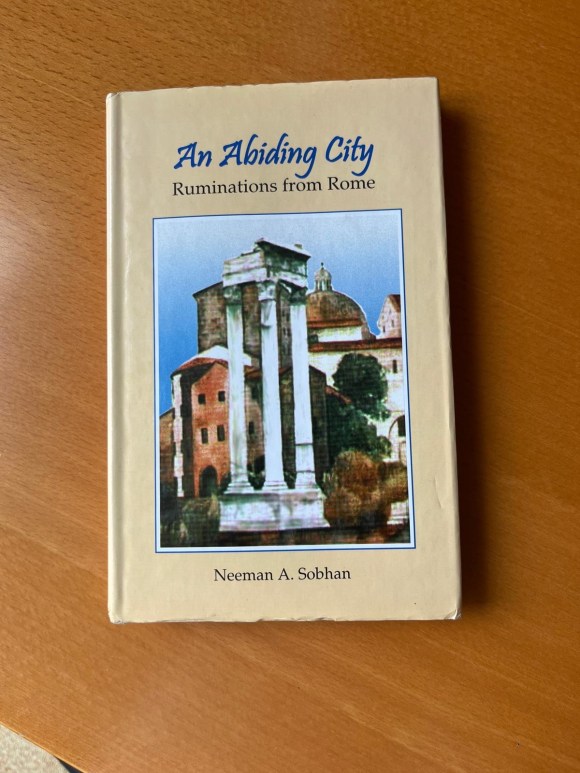

She writes of her compatriots by culture – Bangladeshis — but living often in foreign locales. Her non-fiction, An Abiding City, gives us glimpses of Rome. These musings were written for Daily Star and then made into a book in 2002. Her short stories talk often of the conflicting cultures and the commonality of human emotions that stretch across borders. And yet after living in Rome for 47 years – the longest she has lived in any country – her dilemma as she tells us in this interview – is that she doesn’t know where she belongs, though her heart tugs her towards Bangladesh as she grows older. In this candid interview, Neeman Sobhan shares her life, her dreams and her aspirations.

Where were you born? And where did you grow up?

I was born in Pakistan, rather in the undivided Pakistan of pre-1971: the strange land we had inherited from our grandparents’ and parents’ generation when British colonial India was partitioned in 1947 down the Radcliffe line, creating an entity of two wings positioned a thousand miles apart on either side of India! The eastern wing, or East Pakistan was formerly East Bengal, and my cultural roots are in this part of the region because I come from a Bengali Muslim family. But I was born not there but in West Pakistan, which is culturally and linguistically distinct from Bengal, comprising the regions of Western Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan and the NWFP (North-West Frontier Provinces, bordering Afghanistan), where the official language is Urdu.

So, my birthplace was the cantonment town of Bannu in the NWFP, (now KPK or Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).

Perhaps my life as the eternal migrant, living outside expected geographical boundaries started right there, at birth.

My father’s government job meant being posted in both wings of Pakistan. So, I grew up all over West Pakistan, and in Dhaka, whenever he was posted back to East Pakistan. Much of my childhood and girlhood were spent in Karachi (Sindh), Multan and Kharian (Punjab) and Quetta (Balochistan).

How many years did you spend in Pakistan?

The total number of years I spent in undivided Pakistan (West Pakistan, now Pakistan, and East Pakistan, now Bangladesh) is about two decades, or one year short of twenty years. From my birth in 1954, my growing years, till I left the newly independent Bangladesh in 1973 when I got married and came to the US at the age of nineteen.

What are your memories about your childhood in West Pakistan? I have read your piece where you mention your interactions with fruit pickers in Quetta. Tell us some more about your childhood back there.

I have wonderful memories of growing up in West Pakistan, in Karachi, Multan and Kharian of the late 50’s and early 60’s (despite the era of Martial Law under Field Marshall Ayub Khan, and later his military-controlled civilian government). However, the political environment is invisible and irrelevant to a child’s memories that center around family, school and playmates, till he reaches the teen years and becomes aware of the world of adults. Since, my father’ job entailed us going back and forth between West and East Pakistan, by the time we arrived in Quetta in late 1967, it ended up being my father’s last posting, because by then Ayub Khan’s regime was tottering under protests in both wings of Pakistan; and by the time (I should say in the nick of time) we left for Dhaka, it was already the turbulent year of 1970, which turned Pakistan upside down with General Yahya Khan becoming the new Marshall Law administrator. When we returned to Dhaka, it was the beginning of the end for Pakistan, with preparations for the first democratic general elections, and the blood soaked nine months war of independence for Bangladesh about to be staged.

But as a child, growing up in a Pakistan that was till then my own country, what remains in my treasure trove of memories are only the joys of everyday life, and the friendships (with those whom I never saw again, except one school friend from Quetta with whom I reunited in our middle age in Toronto, Canada!)

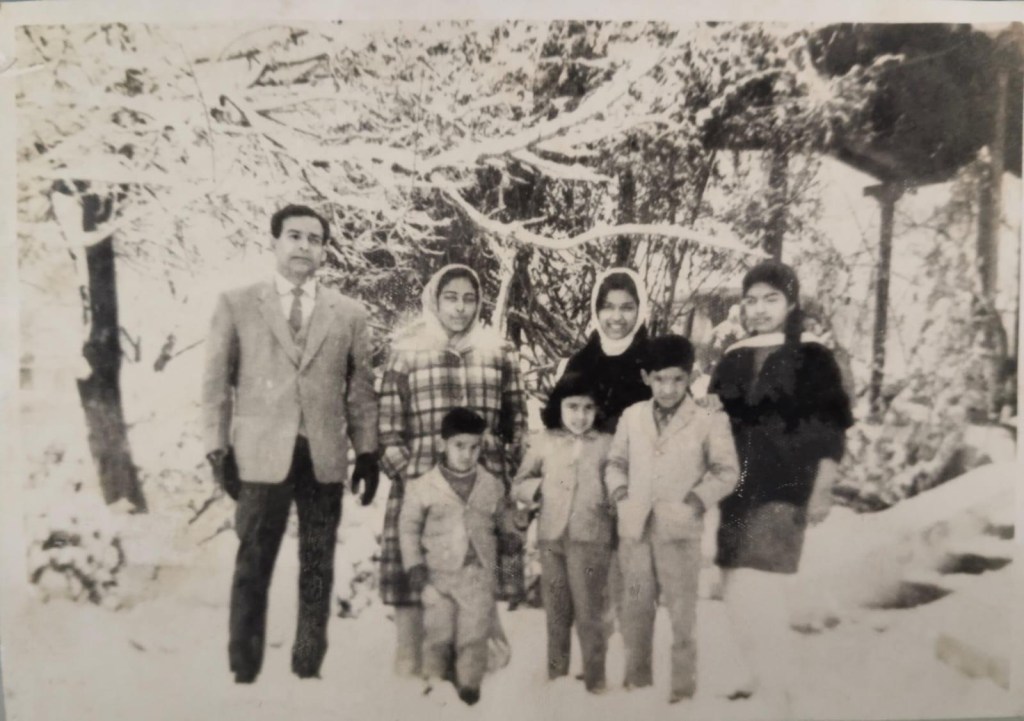

Also precious are the road trips with my five siblings and our adventurous mother, as we always accompanied our father on his official tours, across the length and breadth of West Pakistan.

But if I start to recount all my precious memories, I will need to write a thick memoir. And that is exactly what I have been doing over the years: jotting down my recollections of my past in Pakistan, for my book, a novel that is a cross between fact and fiction. The happy parts are all true, but the sad ones relating to the war that my generation underwent in 1971 as teenagers is best dealt with from the distance of fiction.

What I can offer is a kaleidoscopic view of some random memories: the red colonial brick residence of my family in the 60’s in Multan, one of the hottest cities of Punjab, known for its aandhi — dust storms — that would suddenly blow into the courtyard of the inner garden in the middle of the night as my sister and I slept on charpoys laid out in the cool lawn under a starlit sky, and being bundled up in our parents’ arms and rushed indoors; tasting the sweetest plums left to chill in bowls of ice; being cycled to school by the turbaned chowkidar weaving us through colourful bazars to the Parsi run ‘Madam Chahla’s Kindergarten School’ or on horse drawn tanga (carriages); learning to write Urdu calligraphic letters on the wooden takhta (board) with weed Qalam(pens) and a freshly mixed ink from dawaat (ink pots); and to balance this, my mother helping us to write letters in Bengali to grandparents back in East Pakistan on sky-blue letter pads, our tongues lolling as pencils tried to control the Brahmic alphabet-spiders from escaping the page.

In Karachi, returning home on foot from school with friends under a darkening sky that turned out to be swarms of locusts. Learning later that these grain eating insects were harmful only to crops not humans (and Sindhis actually eat them like fried chicken wings) does not take away the thrill of our adventure filled with exaggerated, bloodcurdling shrieks to vie with the screen victims of Hitchcock’s The Birds, viewed later as adults in some US campus. Picnics and camel rides on the seabeaches of Clifton, Sandspit, or Paradise Point. Near our home, standing along Drigh Road (the colonial name later changed to Shahrah-e-Faisal after King Faisal of Arabia, I later heard) waving at the motorcade of Queen Elizabeth II passing by with Ayub Khan beside her in a convertible with its roof down. That was in the 60’s. Later in 1970, embarking with my family on the elegant HMV Shams passenger ship at Karachi port for our memorable week long journey back to Dhaka across the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean, with a port of call at Colombo in what was still Ceylon, to disembark at Chittagong port, not knowing then that we were waving goodbye not just to the Karachi of our childhood but a part of our own country that would soon become the ‘enemy’ through its marauding army.

But I reset my memories and bring back the beauty and innocence of childhood with images of my family’s first sight of snowfall in Quetta, the garden silently filling with pristine layers of snowflakes piling into a cloudy kingdom under the freshly tufted pine trees, as we sipped hot sweet ‘kahwa’ tea, and cracked piles of the best chilgoza pine-nuts and dried fruits from Kabul. And since Quetta was our last home in Pakistan, I leave my reminiscences here.

There are so many ways to enter the past. Photographs in albums discolor after a time, but words keep our lived lives protected and intact to be accessible to the next generation. I hope my novel-memoir will provide this.

How many countries have you lived in? Where do you feel you belong — Bangladesh, Pakistan, US or Italy — since you have lived in all four countries? Do you see yourself a migrant to one country or do you see yourself torn between many?

I have indeed lived in four countries, for varying lengths of time. In the sense of belonging, each country and stage of my life has left its unique impact. But I have still not figured out where I belong.

Although I lived in Pakistan and Bangladesh from birth till I was nineteen, these were the formative years of my life, and I feel they have coloured who I am fundamentally. The culture and languages of the subcontinent is fundamental to me as a human being. Also, having shared my parent’s experience of being almost foreigners and expats in their own country, trying to speak Urdu to create a Bengali lifestyle at home in a culturally diverse world of Punjabis, Sindhis, Baluchis or Pathans, I know it made them (and us as a family), different from our compatriots in East Pakistan who never left their region and had only superficial understanding of the West Pakistanis. My introduction to a migrant’s life and its homesickness started there, observing my parents’ life.

When I moved to the US after my marriage in 1973, it was to follow my husband Iqbal, to the Washington-Maryland area, where he had moved earlier as a PhD student after giving up, in 1971, his position in the Pakistani central government where he was an officer of the CSP (Civil Service of Pakistan) cadre. These were the days of being newly married and setting up our first home, albeit in a tiny student’s apartment, because more than as a home maker, I spent 5 years attending the University of Maryland as an undergraduate and then a graduate student. We thought our future might be here in the US, he working as an economist for a UN agency, and I teaching at a university. A classic version of the upwardly mobile American immigrant life.

But before we settled down, we decided to pursue a short adventure, and Iqbal and I came to Italy in 1978, from the US, on a short-term assignment with FAO, a Rome based agency of the UN. The mutual decision was to move here, temporarily! We would keep our options open for returning to the US if we did not like our life in Italy.

Well, that never happened! And given the fact that since then, we have spent the last 47 years in Italy, the Italian phase of my life is the longest period I have ever spent in any country in the last 71 years!

Meanwhile, we slowly disengaged ourselves from the US and it was clear that if we had to choose between two countries as our final homes, it would be between Bangladesh, our original home country, and Italy our adopted home.

Still, living away from ones’ original land, whether as an expatriate or an immigrant, is never easy. Immigrants from the subcontinent to anglophone countries like the US, UK, Canada, Australia etc, do not face the hurdles that migrants to Italy do in mastering the Italian language. I am still constantly trying to improve my language skills. Plus, there is the daily struggle to create a new identity of cultural fusion within the dominant and pervasive culture of a foreign land

So, in all these years, though I love Italy and my Roman home, I do not feel completely Italian even if my lifestyle incorporates much of the Italian way of life. For example, after a week of eating too much pasta and Mediterranean cuisine my husband and I yearn for and indulge in our Bengali comfort food. Although I enjoy the freedom and casual elegance of Italian clothes, I look forward to occasions to drape a sari, feeling my personality transform subtly, softly.

Yet, I cannot conceive of choosing one lifestyle over the other. The liberty to veer between different ways to live one’s life is the gift of living between two or more worlds.

The only incurable malaise, though, is the chronic nostalgia, especially during festivals and special occasions. For example, when Eid falls on a weekday, and one has to organise the celebration a few days later over a weekend, it takes away the spontaneous joy of connecting with one’s community, forcing one instead to spend the actual day as if it were an ordinary one. I miss breaking my fasts during the month of Ramadan with friends and family over the elaborate Iftar parties with special food back in Dhaka or celebrating Pohela Boishakh (Bengali new year) or Ekushey February (21st February, mother language day) in an Italian world that carries on with its everyday business, unaware of your homesickness for your Bengali world. Over the years, when my sons were in school, I made extra efforts for. But you know you cannot celebrate in authentic ways.

Of course, these are minor matters. And I am aware that by virtue of the fact that I have dual nationality (I’m both an Italian citizen, and a Bangladeshi), I cannot consider myself a true and brave immigrant — someone who leaves his familiar world and migrates to another land because he has no other options nor the means to return; rather, I feel lucky to be an ex-patriate and a circumstantial migrant — someone who chooses to make a foreign country her home, with the luxury of being able to revisit her original land, and, perhaps, move back one day.

Meanwhile, I feel equally at home in Italy and in Bangladesh because we are lucky to be able to make annual trips to Dhaka in winter.

Whether I am considered by others to be an Italo-Bangladeshi or a Bangladeshi-Italian, I consider myself to be a writer without borders, a global citizen. I feel, I belong everywhere. My home is wherever I am, wherever my husband and my family are. My roots are not in any soil, but in relationships.

I often quote a line by the Mexican poet Octavio Paz. “Words became my dwelling place.” It resonates with me because for me often, it is neither a tract of land, nor even people, but language, literature and my own writings that are my true sanctuary, my homeland. I feel blessed to have the gift of expressing myself in words and shaping my world through language. My home is etched on the written or printed page. My books are my country. It’s a safe world without borders and limits.

Maybe it’s the conceit of a writer and a migrant, nomadic soul, but I think our inner worlds are more substantial than our external ones.

When I read your writing, I find a world where differences do not seem to exist among people in terms of nationality, economic classes, race or religion. Is it not far removed from the realities of the world we see around us? How do you reconcile the different worlds?

I believe and trust in our common humanity, not the narrowness of nationality, race or religion. Nationality particularly is limiting, dependent on land, and boundaries that can shift due to physical or political exigencies. Nationality by conferring membership also necessarily excludes on the basis of manmade criteria, while humanity is boundless, all encompassing, and inclusive, based on shared natural, biological, and spiritual traits.

In my case, I consider the whole world my family. I say this not just as idealistic hyperbole and wishful thinking, but from the fact that I have a multi-cultural, multi-racial family. Only my husband and I are a homogenous unit being Bengali Muslims by origin, but both my sons are married outside our culture, race and religion. One of my daughters in law is Chinese, the other has an English-French father and a Thai mother. So, through my grandchildren, who are a veritable cocktail, yet my flesh and blood, I am related to so many races. How can I bear malice to any people on the globe? The whole world is my tribe, my backyard, where we share festivals and food and rituals and languages. We celebrate unity in diversity.

Kindness and caring for others are values I hold dear in myself and others. I believe in sharing my good fortune with others, and in peaceful co-existence with my neighbours, wherever I live. I believe in living with responsibility as a good citizen wherever I find myself. And so far, the world that I see around me, perhaps narrow, is peopled with those who invariably reflect my own sense of fraternity. Maybe I am foolish, but I believe in the essential goodness of humanity, and I have rarely been disappointed. Of course, there are exceptions and negative encounters, but then something else happens that restores ones faith.

Love is more powerful than hate and generates goodness and cooperation. Change can happen at the micro level if more people spread awareness where needed. Peace can snowball and conquer violence. The human will is a potent spiritual tool. As is the power of the word, of language.

Literature is about connections, communications, bridges. It can bring the experiences and worlds of others from the margins of silence and unspoken, unexpressed thoughts and emotions into the centre of our attention. It brings people who live in the periphery within our compassionate gaze. Language is one of the most effective tools for healing and building trust. Responsible writers can persuasively break down barriers and make the world a safe home and haven for everyone, every creature.

You have a book of essays on Rome, short stories and poems set in Rome. Yet you call yourself a Bangladeshi writer. You have in my perception written more of Rome than Bangladesh. So which place moves your muse?

Any place on God’s beautiful earth can move my muse. Still, the perception is not completely accurate that I have written more of Rome than Bangladesh. It is true that many of my columns, short fiction or poems are set in Rome, but they are not necessarily just about Italy and Italians. In fact, my columns and poems were written from the perspective of a global citizen, who celebrates whichever place she finds herself in.

Poetry, in any case, is never just about any place or thing, but a point of departure. It always goes beyond the visual and the immediate and transcends the particular to the philosophical. The sight of a Roman ruin may jumpstart the poem, but what lifts it into the stratosphere of meaningful poetry is the universal, the human. For example, even when my poem speaks of a certain balcony in Verona, the protagonist is not a girl called Juliet but the innocence of first love, in any city, in any era.

My book of short stories, even when located in Rome, actually concern characters that are mostly Bangladeshi. In fact, it is my fiction that makes me a Bangladeshi writer, because my stories are ways for me to preserve my memories of the Bengali world of my past and an ephemeral present. I write to root myself. I often feel that I should write more about the new Italians, the Bangladeshi immigrants generation, rather than the expats of my generation, but my writing stubbornly follows its own compass.

Regarding my book of essays, my original columns for the Daily Star were written about many other cities I travelled to, including Dhaka and places in Bangladesh, and encounters with people in various countries not just Italy. Constrained to select columns from two decades of weekly writing, for a slim volume to be published, I narrowed the field of topics to Italy and Rome. But I had many essays and travel pieces concerning China, Russia, Vietnam, Egypt, Brazil, Spain, Netherlands and many other European cities and Asian capitals. In the end, a handful of columns about Italy became my book An Abiding City: Ruminations from Rome.

However, in the preface I said: “I must remind that the scope of the book, as suggested in the title, is ‘Ruminations FROM Rome’ not ‘Ruminations ON Rome’ with a tacit emphasis on ‘from’ because the writing relates to matters not just concerning ROME but also encompasses reflections of a more general kind. This is a collection of writings from a columnist who, within her journey through the Eternal City, also attempts to share with her readers her passage through life. I wish my fellow travellers a smooth sojourn into my abiding city, the one WITHIN and WITHOUT.”

I know that had I not lived in Rome but, say, Timbuctoo, I would find something to inspire me to write about. Of course, I am privileged to have lived in Rome and Italy, but nature is beautiful everywhere, in its own way, and there are other civilisations with rich cultures, histories, arts, cuisines, poetry and philosophy that can inspire the sensitive observer and writer.

My elder son lives in Jakarta, my younger son in Bangkok and in all the years of visiting them, I am blown away by the culture and beauty of the Indonesian and Thai worlds, and I have a notebook full of unwritten essays. And there is still so much of the world I have not seen, yet every part of this wondrous earth including my backyard is a chapter in the book of human knowledge. So, had I never left Bangladesh I would still have written. Perhaps “Doodlings from Dhaka!”

What inspires you to write?

Many things. A face at a window, a whiff of a familiar perfume, an overheard conversation, a memory, a sublime view…. anything can set the creative machine running. Plus, if I’m angry or sad or joyous or confused, I write. It could become a poem, fiction, or a column.

The writer in me is my inner twin that defines my essential self. I am a contented wife of 52 years of marriage, a mother of two sons, and a grandmother of four grandsons (aged 8-7-6-5). These roles give me joy and help me grow as a human being. But my writer-self continues on its solitary journey of self-actualisation.

Yet, I write not just for myself, I write to communicate with others. I write to transmit the nuances of my Bengali culture and its complex history to my non-Bengali and foreign readers and students, but more importantly to my own sons, born and brought up in Italy, and my grandchildren, whose mothers (my daughters-in-law) are from multi-cultural backgrounds, one a Chinese, and the other a combination of English, French and Thai. I write also for the younger generation of Bengalis, born or raised abroad, who understand and even speak Bangla, but often cannot read the language, yet are curious about their parents’ world and their own cultural heritage.

What started you on your writerly journey? When did you start writing?

I have always written. As an adolescent, I wrote mostly poetry, and also kept a journal, which I enjoyed reading later. It created out of my own life a story, in which I was a character enacting my every day. It clarified my life for me. Interpreted my emotions, explained my fears and joys, reinforced my hopes and desires. Writing about myself helped me grow.

My columnist avatar is connected to this kind of self-referral writing, but in real life it emerged by accident when I was invited to write by the editor of the Daily Star. The act of producing a weekly column was a learning experience, teaching me creative discipline and the ability to marshal my life experiences for an audience. I learnt to sift the relevant from the irrelevant and to edit reality. What better training for fiction writing? For almost two decades my experience as a columnist was invaluable to my writer’s identity.

Soon I concentrated on fiction, especially short stories that were published in various anthologies edited by others in Bangladesh, Pakistan and India. I now realised that while column writing was about my life in the present tense and about the daily world around me, my fiction could finally involve the past. The result was my collection of short stories: Piazza Bangladesh.

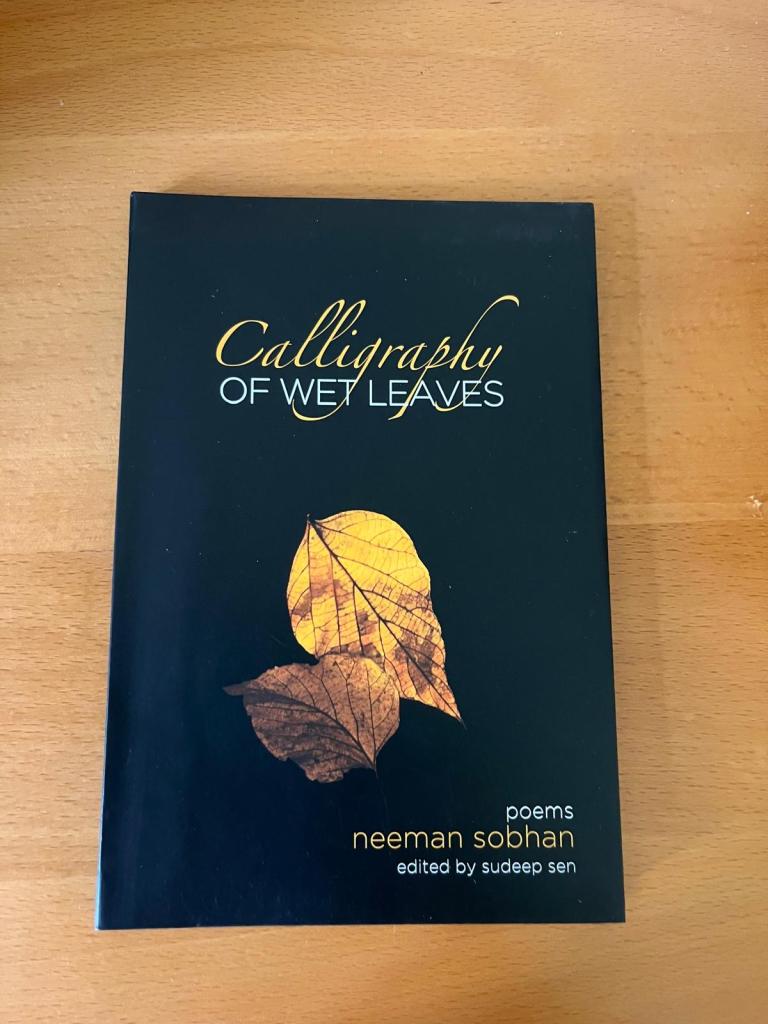

Ironically, it was my book of poems, Calligraphy of Wet Leaves that was the last to be published.

Your short stories were recently translated to Italian. Have you found acceptance in Rome as a writer? Or do you have a stronger reader base in Bangladesh? Please elaborate.

Without a doubt, as an anglophone writer, my reader base is better not just in Bangladesh, but wherever there is an English readership. However, books today are sold not in bookshops but online, so these days readers live not in particular cities or countries but in cyberspace.

But living in Italy as a writer of English has not been easy. The problem in Italy is that English is still a foreign and not a global language, so very few people read books in the original English. Every important or best-selling writer is read in translation. This is unlike the Indian subcontinent where most educated people, apart from reading in their mother tongues, read books, magazines and newspapers in English as well.

This is why I was thrilled to finally have at least one of my books translated into Italian, and published by the well-known publishing house, Armando Curcio, who have made my book available at all the important Italian bookstore chains, like Mondadori or Feltrinelli. Also, through reviews and social media promotion by agents and friends, and exposure through book events and literary festivals in Rome, including a well-known book festival in Lucca, it has gained a fair readership.

That’s all I wish for all my books, for all my writing, that they be read. For me, writing or being published is not about earning money or fame but about reaching readers. In that sense, I am so happy that now finally, most of my Italian friends and colleagues understand this important aspect of my life.

You were teaching too in Rome? Tell us a bit about your experience. Have you taught elsewhere. Are the cultures similar or different in the academic circles of different countries?

I taught Bengali and English for almost a decade at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the University of Rome, La Sapienza., till I retired, and it was an enriching experience.

I studied for a year at the University of Dhaka before I got married and came to the US in 1973, where I continued my studies at the University of Maryland, earning my B.A in Comparative Literature and M.A in English Literature. I mention this because these experiences gave me the basis to compare the academic cultures in the Bangladeshi, American and Italian contexts.

I discovered more in common between the Bangladeshi and Italian academic worlds, especially regarding the deferential attitudes of students towards their teachers. In Italy, a teacher is always an object of reverence. In contrast, I recall my shock at the casual relationships in the American context, with students smoking in front of their teachers, or stretching their leg over the desk, shoes facing the professor. Of course, there was positivity in the informality and camaraderie too, between student and teacher. But with our eastern upbringing we cannot disregard our traditional veneration of the Guru and Master by the pupil.

In Italy it was rewarding for me to have received respect as a ‘Professoressa’ while teaching, and even now whenever I meet my old students. However, some of the negative aspects of the academic world in Italy linked to the political policies that affect the way old institutions are run, cause students to take longer to graduate than at universities in the UK or US for example.

Are you planning more books? What’s on the card next?

I have a novel in the pipeline, a fusion of fiction and memoir, that has been in gestation for more than a decade. Provisionally titled ‘The Hidden Names of Things’, it’s about Bangladesh, an interweaving of personal and national history. It’s almost done, and I hope to be looking for a publisher for it soon. Perhaps, it has taken so long to write it because over the years while the human story did not change much, the political history of the country, which is still evolving through political crises kept shifting its goal posts, impacting the plot.

Most of my writings illustrate, consciously or inadvertently, my belief that as against political history our shared humanity provides the most satisfying themes for literature.

To share my stories with a readership beyond the anglophone one, my collection of stories ‘Piazza Bangladesh’ was translated into Italian and published recently in Italy, as ‘Cuore a Metà’ (A Heart in Half) which underlines the dilemma of modern-day global citizens pulled between two worlds, or multiple homes.

Meanwhile, my short stories, poems and columns will be translated into Bengali to be published in Dhaka, hopefully, in time for the famous book fair in February, Ekushey Boimela. Then my journey as an itinerant Italian-Bangladeshi writer will come full circle and return home.

(This online interview is by Mitali Chakravarty)

Click here to read an excerpt from An Abiding City: Ruminations from Rome

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International