Title: One More Story About Climbing a Hill: Stories from Assam

Author: Devabrata Das (translated from Assamese by multiple translators)

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

1. A Night with Arpita

(‘Arpitar Erati’ translated by Meenaxi Barkotoki)

The side berth was created by lowering the back rests of the two single seats along the aisle of the compartment. Crouching in one corner of that berth, chin in her hands, eyes looking out of the window, could the expression on her face be called disinterest, or was it heartache? On the other hand, she had not the slightest curiosity about what was going on inside the compartment. Drawing the free end of her sari tightly around the upper half of her body, she had withdrawn even her feet into the cavity created by her sari. Her presence in the compartment seemed more like an absence. She seemed completely oblivious and unaware of her surroundings; her look betrayed a sense of resignation. Or perhaps of surrender.

Having positioned myself in the compartment, the sense of resignation that was evident in her demeanour attracted me to her the very first time that I looked at her attentively. I told myself that if I wrote a story someday on the girl, I would name her Arpita (the one who offers herself). Arpita what? Ganguly or Acharya, Roy or Majumdar? Because on hearing the Hindi strewn with Bengali words spoken by the girl’s father, (who had complained animatedly to the waiter about the stale fish served for the meal) I was certain that the girl was not an Assamese disguised in a sari, she was actually Bengali. Regardless of whether she was Assamese or Bengali, she was just a girl, a more or less pretty girl, and she was presently in another world, completely oblivious to her surroundings. Her entire being was concentrated on a point in the darkness of the world outside the compartment, a point that could easily be defined as infinity. Her absentminded beauty aroused my curiosity. Puffing at my Charminar cigarette I kept staring at her from my middle berth in the three-tiered compartment. Just then Kiran returned from the bathroom and broke my reverie. ‘What is this? Why are you already in bed? You don’t mean to go to bed so early, do you?’

This story is actually the story of Arpita and me. I am the protagonist, Arpita the heroine. Apart from the two of us, there is no need for anyone else in this story. The problem, however, is that in order to be able to describe the chain of events, the inclusion of some redundant characters becomes necessary; their presence in the story is not essential but without them it is difficult to narrate what happened. Among those extras, unnecessary characters actually, one is my friend Kiran Debnath. We work in the same office and it is on official work that both of us are travelling by train to another city. We had to travel at very short notice, so we had no reserved train seats; hence the second unnecessary character, Krishna, became necessary. Krishna lives in our neighbourhood. A young man barely out of his teens, he had recently joined the NF Railway as Travelling Ticket Inspector, in short TTI. The moment I saw him at the train station, I was relieved; we wouldn’t have to travel in the crowded, unreserved compartment after all. Since Krishna was there, with his help we would get at least two sitting seats for ourselves. But luckily there was not a huge rush that day and after doing the rounds, Krishna arranged two sleeping berths in a three-tier compartment for us. The sleeper charges for a night are five rupees fifty paise each, so eleven rupees in all. I gave him three five-rupee notes. He forgot to return the change. A little while after the train started, another uniformed ticket checker came and wrote out our reservation slips. The fourth unnecessary character in this story is Arpita’s father, who, after finishing the long and animated argument with the waiter about the stale fish served for dinner, turned his attention to his daughter. She was still staring out of the window. He told her to lie down and go to sleep, and gave her other sundry bits of advice, all of which were met with monosyllabic answers. He then climbed onto the upper berth, above his daughter. In a little while, his snoring proved that he was fast asleep. This is the last time I will mention these unnecessary characters, except for Kiran.

I told Kiran that we had a lot to do the next day. We would have to go through all the documents and records of our branch office in the town we were travelling to. It was not clear whether we would have any free time at all. So instead of sitting up chatting till late in the night, since we had secured two sleeping berths, it might be wiser to go to sleep. Like a good boy, Kiran agreed immediately and went to sleep in the berth below me. To tell the truth, I was not at all sleepy. If I had wanted to or if we were somewhere else, I would have easily chatted with Kiran for an hour or two. But at that moment, in that situation, the single-minded desire to enjoy the distracted attractiveness of a beautiful girl made me give up the wish to chat with Kiran.

Arpita sat immersed in herself on the rattling train, on that otherwise still night, ignoring the silent presence of the many other passengers sleeping in the compartment. No exam results had been declared recently. Then why was Arpita so unwaveringly distracted and sad? Was her pain intensely personal? For instance, had some sly lover cheated her and gone away, after having made a thousand promises of many-hued rainbows and eternal love? Or was there some complication in her recent wedding proposal? Had the partner that her parents chose for her, seen and approved of her but demanded a huge dowry, which made it completely impossible for her to leave her parents’ home? What could it be? What was her real story?

(Extracted from One More Story About Climbing a Hill: Stories from Assam by Devabrata Das, Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2025.)

About the Book:

In ‘A Night with Arpita’, a beautiful young girl in a train compartment captures the imagination of the writer—but he is unable to fathom the reason for her melancholy until it is too late. In ‘Ananta with His Seema’, three apparently disconnected incidents take place on a railway platform. Descriptions of the incidents are interspersed with passages from a letter written by Ananta’s friend, that lays bare his helplessness in the face of injustice and the loss of his youthful ideals.

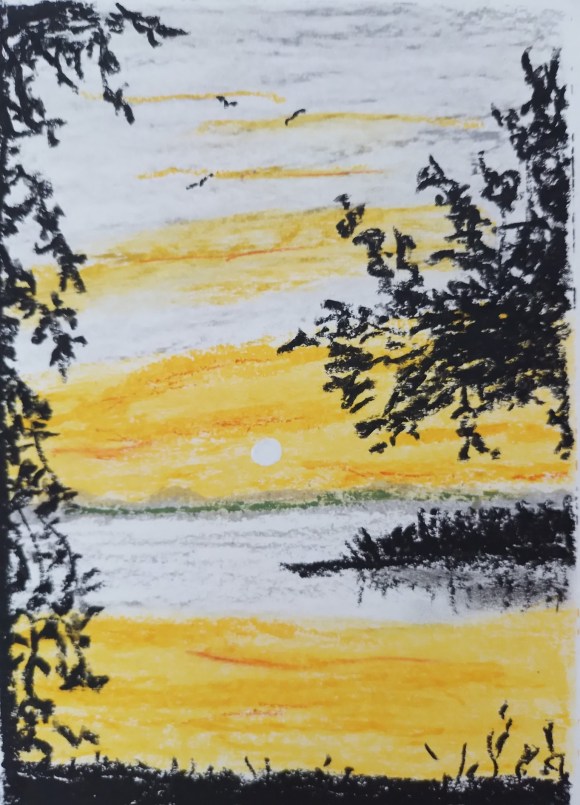

In the eponymous story, life imitates art with a disastrous twist. A young couple treks up a hillside to recreate for themselves the experience of two characters in a love story set in idyllic Shillong. But the beauty of the pine shrouded hills is marred by extremist violence and their climb to the top of the hill has an unforeseen, macabre end.

Each of the eighteen stories, translated by multiple translators, in this collection provides an insight into life in an area of conflict, told with irony and ingenuity. Regarded as a torchbearer of post-modernism in Assamese literature, Das is often a character in his stories, blurring the distinction between writer and narrator and, often, between fiction and reality, leaving readers to construct their own endings. This first English translation of his work is a valuable addition to the pantheon of India’s regional literature.

About the Author

Devabrata Das is considered to be a torchbearer of post-modernism in Assamese literature, following in the footsteps of other great Assamese writers such as Saurav Kumar Chaliha and Bhabendra Nath Saikia. With more than twenty-five bestselling books to his credit in a career spanning more than four decades, his repertoire ranges from fiction to non-fiction, and from screenplays to reviews and critical essays. He received the Sahityarathi Lakshminath Bezbarua Award in 2018, the Sahitya Sanskriti Award of the literary organization Eka Ebong Koekjan in 2010, and the Tagore Literature Award of the Sahitya Akademi in 2011.

About the Translator

Meenaxi Barkotoki is a mathematician turned anthropologist by profession. An avid translator from Assamese into English, her most recent work includes a couple of novels, notably a children’s novel by Arupa Patangia Kalita titled Taniya (Puffin Classics, 2022). Her translations have appeared in newspapers and periodicals as well as in prestigious compilations like The Oxford Anthology of Writings from North-East India (OUP, 2011) and in Asomiya Handpicked Fictions (Katha, 2003). She also writes short stories, travel pieces and current interest articles, and her work has been published in newspapers, journals and magazines. She is a Founding Member of the North East Writers’ Forum.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.