By Ravi Shankar

The wind blowing across the Long Island Sound chilled his bones. The day was cloudless and the sky blue, but the sun lacked warmth. New York. Dr Ram Bahadur had called the big apple home for over three decades. Winters were cold and snowy. There were cold snaps and the dreaded northeaster brought snow and freezing temperatures. Summers could be surprisingly warm. February in New York was the depth of winter.

Long Island was blanketed in snow. He had spent the morning clearing snow from the driveway of his home. The suburb of Woodbury was quiet and peaceful. The trees had lost their foliage and were waiting for the warmth of spring to put on a new coat of green. He had a large house with floor to ceiling picture windows. The house was two storied with an attic. There were two bedrooms on the ground and three on the first floor. He had done well in life and was now prosperous.

He still recalled his first days in the big apple. He had just come to the United States from Nepal after completing his postgraduation in Internal Medicine. The first years were tough. He had some seniors doing their residency in New York city. The state of New York offered the largest number of residencies in the country. He did his residency again in internal medicine and then a fellowship in endocrinology.

All his training was completed in New York. He worked for over two decades in large hospital systems. But, for the last five years he started his own private practice. Compared to most other countries medicine in the States paid well. Private practice was certainly lucrative, though the cost of living in New York was high.

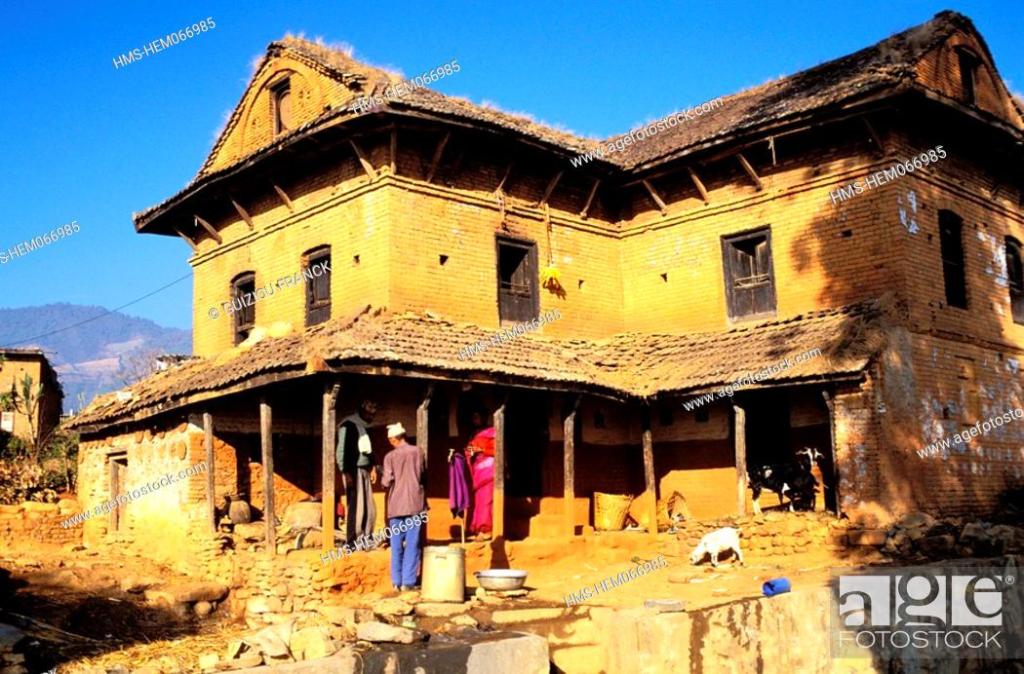

He did sometimes think about his home country of Nepal. The Kathmandu valley was still a beautiful place. His visits were few and far in between. Unplanned urbanisation had made the valley dusty and dirty. Winters in Kathmandu were cold but milder compared to New York. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was the first medical school established in the country. The original intention was to create doctors for rural Nepal. The selection was tough and competitive. He still remembered his joy on learning that he had been selected for the medical course. During the closing decades of the twentieth century Nepal was in turmoil. The insurgency was ongoing, and blockades were the order of the day. Violence was rife and a lot of blood was spilled.

Most doctors from IOM migrated in search of greener pastures. The others mostly practiced in the valley, the historic heartland of the country. Ram was originally from Gorkha, in the centre of the country but his family had migrated to the capital when he was a few years old. His father was a civil servant while his mother was a housewife. Civil servants did not make much and money was always in short supply. His father was a man of principle and never accepted bribes or tolerated corruption. He still remembered the argument he had with his father when he put forward the plan to migrate to the United States (US) to pursue his residency.

His parents had both passed away and his siblings were also settled in North America. He rarely visited Nepal these days. The insurgency was followed by the overthrow of the monarchy and then a new constitution was promulgated. A federal structure was set up and while this did have benefits, the expenditures also increased. Each state had to set up an entirely new administrative machinery. He married an American academician who taught Spanish literature at the City University of New York. His wife’s family hailed from the country of Colombia.

New York had a substantial Hispanic population these days. He was now fluent in several languages: Nepali, his mother tongue; English, Spanish and Hindi. He also understood Newari, the language of the Newars, the original inhabitants of the Kathmandu valley. He did think on and off about his motherland. Many Nepali doctors left the country. Working conditions were hard and the pay was poor. To advance, you required political patronage. The frequent changes in government required you to be on good terms with several political parties.

He still missed the food of his childhood. New York was a very cosmopolitan place. There were several Indian restaurants and even a few Nepali ones. He was very fond of bara (a spiced lentil patty) and chatamari (Newari pizza), traditional Newari foods. These had earlier not been available in New York. Luckily for him, two years ago a Newari restaurant had opened in Queens. He was also particular to Thakali food. The Thakalis were an ethnic group who lived in the Kali Gandaki valley north of Pokhara. He particularly fancied green dal, sukuti (dried meat), kanchemba (buckwheat fries) and achar (pickle). Anil was a decent cook and had learned to cook a decent Nepali thali[1]and dhido (thick paste usually made from buckwheat or corn). He also made tasty momos (filled dumplings that are either steamed or fried) and these were much in demand among his companions.

Ram loved the professional opportunities that his adopted homeland provided. He had become a US citizen. Working in the US was more rewarding though the paperwork associated with medical care had steadily increased. Many of his batchmates and seniors lived and worked in New York state and across the state border in New Jersey.

Many of them did miss their homeland and had a vague feeling of guilt for not contributing their share to their original homeland. A few of them were working on a proposal of developing a hospital at the outskirts of Mahendranagar in the far west of Nepal. The Sudurpashchim province had a great need for quality medical care. The details were still being worked out. There were about twenty IOM graduates involved and they decided on an initial contribution of a million dollars each. Despite inflation twenty million dollars was still a substantial sum in Nepal.

This group of friends collaborated on different social projects. They were also active in promoting a more liberal America where each citizen and resident had access to quality healthcare. The hospital would be their first project outside the US. A strong community outreach component was also emphasised in their project.

The US had made him wealthy. He was a proud American. However, he also owed a deep debt to his home country for educating him and creating a doctor. Now was the time for him to repay that debt, not wholly or in full measure but substantially to the best of his abilities!

[1] Plate made of a few courses, completing the meal

.

Dr. P Ravi Shankar is a faculty member at the IMU Centre for Education (ICE), International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He enjoys traveling and is a creative writer and photographer.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International