Books Reviewed by Somdatta Mandal

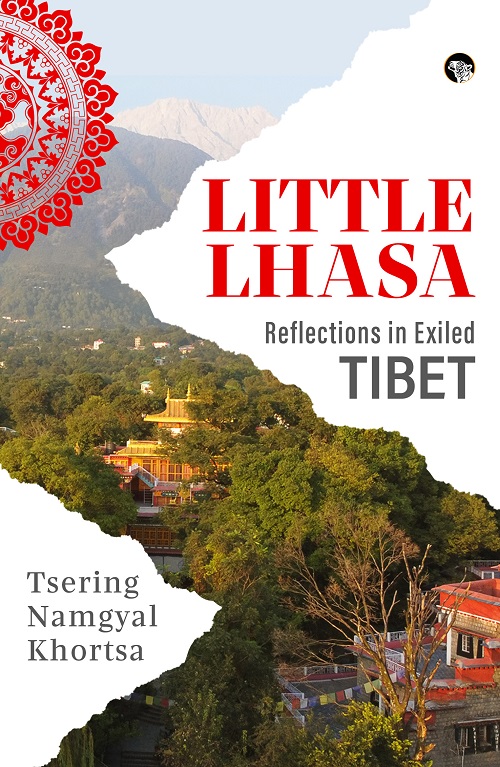

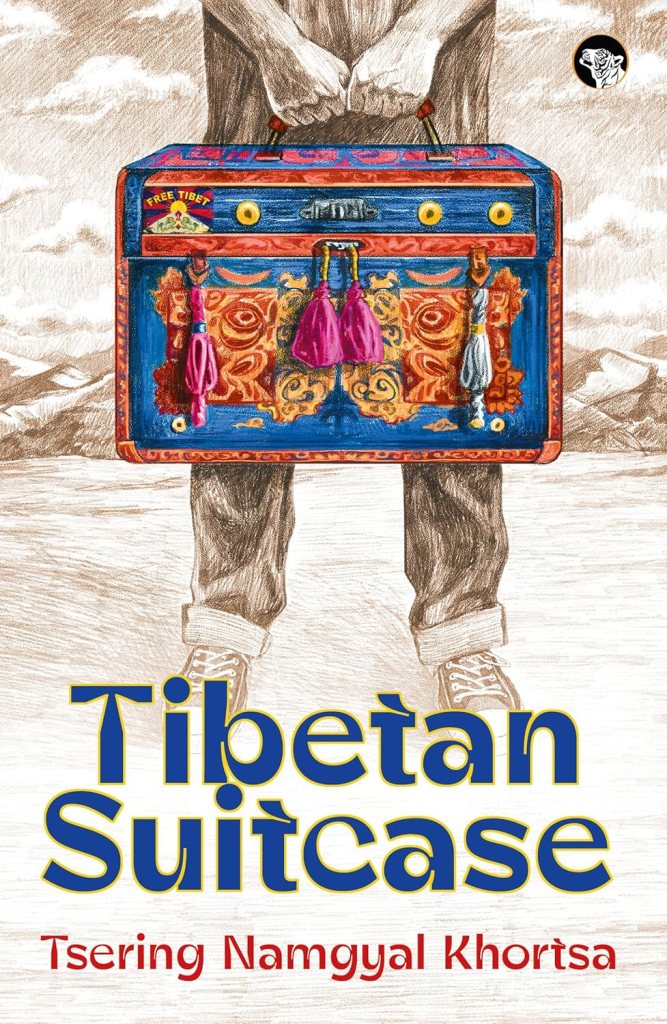

Titles: Little Lhasa: Reflections in Exiled Tibet and Tibetan Suitcase

Author: Tsering Namgyal Khortsa

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Following the forced escape of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in March 1959, thousands of Tibetans were forced to flee Tibet, and it was these refugees who formed the early exiled community. The refugee community now stands at a figure of around 130,000, with Tibetans spread across numerous settlements in India, Nepal and Bhutan, and thousands more displaced all around the world. The Tibetan government in exile is based in Dharamsala, India. It is called the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) and was founded in 1959 by the 14th Dalai Lama. In the 1980s, a second wave of Tibetans fled due to political repression. The CTA advocates for human rights, self-determination, and the preservation of religion and culture for Tibetans. The CTA has a parliament, judiciary, and executive branch and its principles include truth, non-violence, and genuine democracy. The Dalai Lama has said that the exile administration would be dissolved as soon as freedom is restored in Tibet.

After over seventy years of being in exile, a whole generation of Tibetans have come of age in a land far from home. With the Dalai Lama and other great masters as their spiritual guides, they have grown up cut off from their homeland. Their experiences have been unique, as they have, despite globalization, kept alive their religion and culture. In Little Lhasa: Reflections in Exiled Tibet, Tsering Namgyal Khortsa writes comprehensively about the different aspects of their life today. Comprising of ten essays and six interviews, this volume becomes an eye-opener on the multifarious aspects of the present situation of Tibetans at large. Beginning with different writers writing about Tibet and exile in the very first essay titled ‘Little Lhasa’, the next one ‘Shangrila Online’ tells us about the role of social media, internet cafes and how technology in remote Dharamsala often enables one to participate in other people’s experiences in real time. The writer describes in detail how such lifestyle changes in contemporary times have enabled the creation of a “virtual Tibet”. In the next essay ‘Buddha’s Children’, Khortsa describes the young generation of exiled children in India and how their religious identity has triumphed over all other identities. We are also told about the different kinds of foreigners who come to India to take religious courses, and the writer wonders whether they go home feeling merely inspired by their visit to India and their meetings with Tibetan masters or whether such exposure and experience actually triggers a paradigm shift in the way they view the world.

In the next essay we are told how Tibetans lead demonstrations in Dharamsala and other parts of India every year, especially the one held on March 10th that commemorates the anniversary of the failed uprising against Chinese invasion. ‘Movies and Meditation’ mentions a film festival in Dharamsala which reveals how recent Tibetan films highlight a growing and vibrant filmmaking community within the Tibetan diaspora, but Khortsa laments the paucity of full-length films about Tibetans in exile and the issues they confront, namely patriotism, individualism, and reconciliation of personal fulfilment with the Tibetan cause. The titles of the three following essays, ‘Dharma Talk’, ‘The Lure of India’ and ‘The Monk at Manali’ are self-explanatory. The last essay of this section ‘Nation of Stories’ tells us about writers who write and publish in the English language, and though diverse in terms of their education, upbringing, background and geographical location, one common condition that they all share is the collective trauma of the Chinese occupation of Tibet, which is invariably a leitmotif in Tibetan literature.

Part Two consists of six interviews, each one different in perspective than the other, and they must be mentioned here to understand the kaleidoscopic nature of the people involved in the Tibetan cause. Thus, we have conversations with Lisa Gray as ‘A Western Buddhist’, Ananda Nand Agnihotri as ‘An Indian Tibetan Buddhist,’ Ngawang Woeber, ‘An Ex-Political Prisoner’, Nyima Dhondup, ‘A Swiss Tibetan’, Tenzing Sonam, ‘A Tibetan Writer and Filmmaker’ and Tenphun, ‘The Tibetan Poet’. All in all, Little Lhasa becomes a valuable record of the life of a people who refuse to bow down or forget, and even while adapting to a rapidly changing world, continue to nurture their roots.

II

After the non-fiction, Tsering Namgyal Khortsa comes up with a brilliant piece of fiction and read together, each text complements the other beautifully. In the ‘Editor’s Note’ at the very beginning of the novel Tibetan Suitcase, Tsering Namgyal Khortsa tells us that while he was working as a business journalist in Hong Kong he once ran into Dawa Tashi, an old acquaintance and an aspiring novelist from Dharamsala, India who was working as a meditation teacher and was quite busy with his job. He had a suitcase full of letters and documents and wanted him to turn the contents of the suitcase into a book. After going through the collection, Khortsa discovered that the contents of the suitcase, if organized with care and discipline, could indeed make for an epistolary novel. So, he declares that except for correcting a few typos here and there and add note and datelines to the letters, he had not done anything. He also categorically states, “None of the letters are mine, except some entries that I wrote, making the book partly fictionalized.” He also wanted to leave room for readers to imagine (or ‘feel’ for themselves) what is not mentioned in the book, in deference to the Tibetan culture of reticence and taciturnity, rather than turning himself into an all-knowing chatterbox.

Tibetan Suitcase is a remarkable novel about the peripatetic Tibetan community in exile. It is divided into six parts, beginning roughly from 1995 to 2000. It opens in Hong Kong where a tycoon Peter Wong opens a meditation centre and employs Dawa Tashi, our protagonist as a meditation teacher and a guru, though he is not really trained to be a lama. Dawa Tashi is an India-born Tibetan. His parents fled Tibet when the Chinese invaded, and Dawa has grown up in the quiet, verdant Indian Himalayas. When Dawa applies to a well-known university in America (Appleton University in Wisconsin) to pursue a course in creative writing, his hitherto ordinary life changes dramatically. At the university he befriends, and falls in love with, Iris Pennington, an unusual American student who is studying Buddhist literature. He also comes in contact with Khenchen Sangpo, a renowned scholar of Buddhism and a reincarnated Rinpoche himself. Circumstances lead Dawa back to India too soon, but the connections he makes take his life into many new directions. Some, with Iris and Khenchen, take him deeper into the mystical and mysterious world of Buddhist scholarship. Other journeys take him back to his roots, making him question his life’s directions.

Apart from the interesting incidents and characters we meet in the first four parts of the novel, Part Five is an exceptionally engrossing to read. Beginning with the reportage in the Fall Issue of the journal Meridian, which is edited by Brent Rinehart, we are told that on his seventy-ninth birthday Khenchen decided that he had to go back to Tibet to see his native land. Having gained a quick residency status in the United States, and possessing an American passport, Khenchen still had many relatives in Tibet, some of them quite alive and well, despite the Chinese occupation. He travels to Lhasa in 1996 and goes for a trip to Lake Manasarovar but things take a different turn when he is arrested by the Chinese authority because he was apparently “endangering national security”. What follows are different press releases from the US Statement Department, reports from the International Association of Tibetan Studies in London, address by the President of Appleton University and as Iris writes to Dawa, she never expected herself to be so politically involved and “did not realize Tibet was such a political subject”. It was ironic that one of the world’s most spiritual places was one of its most burning political issues. Tibet might be a small place, but it has a reasonably big space in the collective consciousness of the world. Of course, Khenchen Sangpo is ultimately released and without disclosing the actual ending of the novel, which in a circular fashion ends in Hong Kong from where it began, many loose ends are tied up and life came to a full circle for everybody, especially for Iris Pennington who finally managed to find her roots.

Both the non-fiction and the fiction book by Tsering Namgyal Khortsa prove to be eye-openers for all readers who have very little knowledge about the sorrow and plight of the uprooted Tibetans who live in exile and many of whom do not even have a country to call their own. Based in Dehradun, India at present, Khortsa’s narratives are so powerful that it has aptly prompted Speaking Tiger Books to reprint the updated versions of both the books in 2024 and one can call it a yeoman service to readers both serious and casual. A must read.

.

Somdatta Mandal, critic and translator, is a former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International