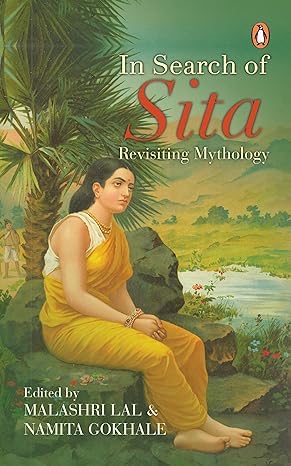

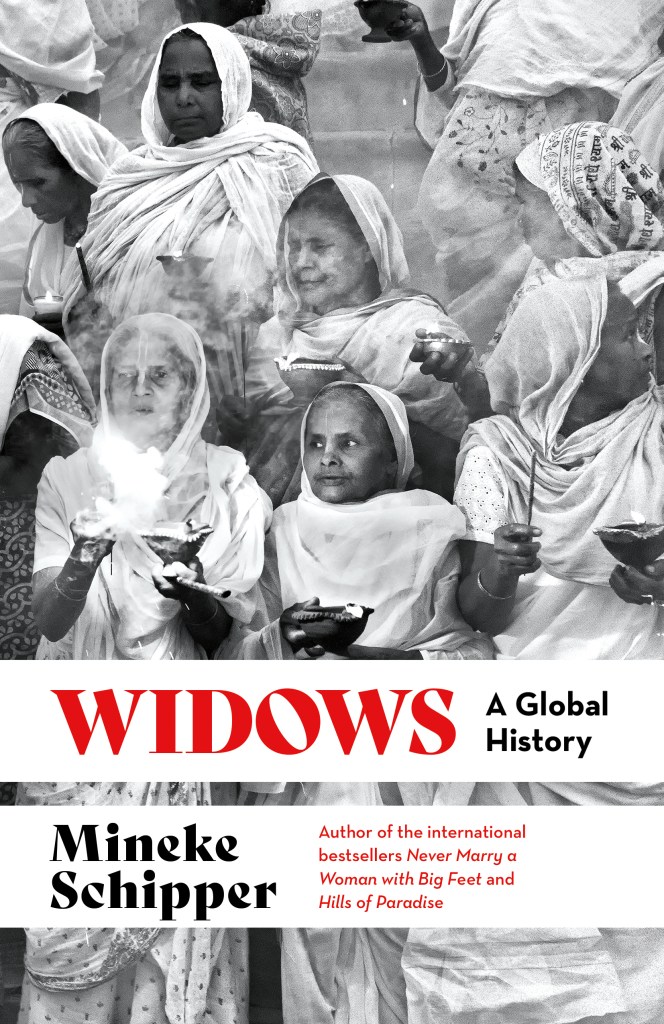

A brief review of Mineke Schipper’s Widows: A Global History (Speaking Tiger Books, 2024) and a conversation with the author

To conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom.

—Bertrand Russell, Unpopular Essays (1950)

This is one of the dedications that precedes the narrative of Mineke Schipper’s non-fiction, Widows: A Global History. Her description of misapprehensions and the darkness around widowhood, as well as the actions that have been taken and suggestions on how more can be done to heal, weave a narrative for a more equitable society.

Starting with mythological treatment of widows, the book plunges into an in-depth discussion, not just with case studies but also with a social critique of the way these women are perceived and treated around the world, their need to heal from grief or a sense of devastation caused by their spouse’s death, concluding with stories that reflect the resilience of some of those who have overcome the odds of being repulsed. It is a book that inspires hope… hope for a world where despite all stories of misogyny covered in media, there are narratives that showcase both the human spirit and humanity where the ostracised are moving towards being integrated as a part of a functional social sphere.

Schipper, best known for her work on comparative literature mythologies and intercultural studies, navigates through multiple cultures over time and geographies to leave a lingering imprint on readers. She writes: “In Book V of his Histories, Herodotus (485-425/420 BCE) described life among the Thracians: Each man has many wives, and at his death there is both great rivalry among his wives and eager contention on their friends’ part to prove which wife was best loved by her husband. She to whom the honour is adjudged is praised by men and women alike and then slain over the tomb by her nearest of kin. After the slaying she is buried with the husband.” And yet she tells us of the dark past of Europe, “A Polish text asserts with great certainty that, after the burning of the body of her husband, ‘every wife allowed herself to be beheaded and went with him into death’.” She tells us stories of wife burning, killing and dark customs of yore across the world that seem like horror stories, including satis in India. The “motivation” is often greed of relatives or customs born of patriarchal insecurities. She contends, “wherever desperate poverty reigns, widows are at an increased risk.”

She argues: “The story is much the same everywhere; widows who are well educated know what rights they have or are able to find the right authorities to approach with their questions, while women with little or no education continue to suffer from malevolent practices.”

She has covered the stories that reflect the need for the welfare of widows, of how early marriages lead to widowhood even in today’s world ( “ Every year around twelve million girls under the age of eighteen get married, one in five of all marriages.”), of social customs like dowry, which can be usurped by a widow’s spouse’s family, of steps that are being taken and changes that need to be instituted for this group of women often regarded in the past and even in some places, in the present, as witches. In fact, she has written of such ‘witch villages’ in Africa, which have been developed to help widows who have been treated badly and turned away from their homes. Such stories, she tells us prevail all over the world, including India, where widows are sent or go to Varanasi.

She asserts that despite these efforts, “there is often still a significant gap between declarations of gender equality and their day-to-day enforcement and application.” She ends with case studies of four women: “Christine de Pisan, Tao Huabi, Laila Soueif and Marta Alicia Benavente examples of widows who dared to fully throw themselves into a new life following the death of their husbands.” And with infinite wisdom adds: “We cannot change history, but we can look to the past with new knowledge and to the future with new eyes.” She concludes with a profound observation: “Time does not heal sorrow, but out of the centuries-old ashes, grief, strict commandments and prohibitions, new prospects can also rise. The fact that every person’s life is finite makes every day unique and precious. The same goes for widows.”

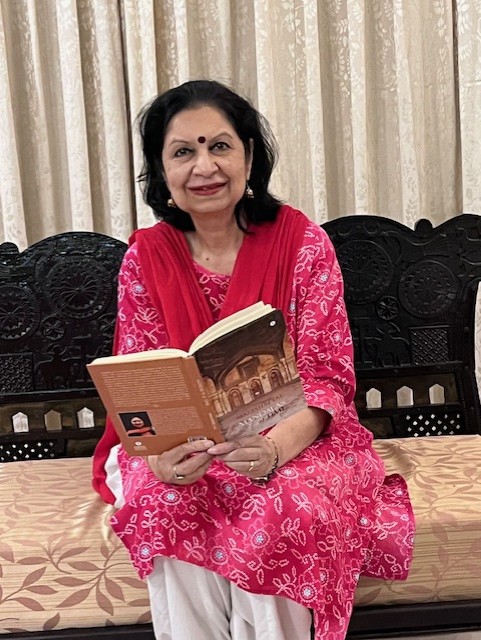

In this interview Mineke Schipper (née Wilhelmina Janneke Josepha de Leeuw), an award-winning writer from Netherlands, tells us what started her on her journey to uncover the stories of this group of people.

What got you interested in widows as a group from around the world? Why would you pick this particular group only for a whole book?

Yes, whence this topic? The widow had been a tiny part of Never Marry a Woman with Big Feet. Women in Proverbs From Around the World (Yale UP 2004), an earlier book I wrote about proverbs referring to women’s lives, from girl babies to brides, wives and co-wives, mothers and mothers-in-law, grandmothers and old women. It was a long and breathtaking study about more than 15,000 proverbs, collected over many years, apparently widely appreciated and translated with two relatively recent editions published in India, in English and in Marathi. For those interested: the complete collected material is accessible and searchable at www.womeninproverbsworldwide.org, including proverbs about widows. That small but striking section about widows had made me curious, but other books, as it goes, pushed ahead, before I came back to them. In January 2020, I had to look up something in that book about proverbs, and the pages about widows looked so weird that I proposed the widow as my new topic to my Dutch publisher who responded enthusiastically.

You have written of so many cultures and in-depth. How long did it take you to collect material for this book and put it together?

All over I found obvious warnings and distrust viz a viz a woman whose husband dies. Interestingly, a widow was associated with death—and a widower was not. Take heed, suitor, when you replace the dead husband in the widow’s conjugal bed! Better not! Was it the fear that she had killed him? Or the creepy thought that the dead man’s hovering ghost was still hanging around? A widow was supposed to mourn intensely over her husband, preferably the rest of her life. In the meantime, proverbial messages openly expressed the widower’s happiness at the news of his wife’s death: ‘Grief for a dead wife lasts to the door’ (all over Europe) or ‘A wife’s death renews the marriage’ (Arabic). I came across well-known names—such as Confucius, Herodotus, Boniface, and Ibn Battuta—and lesser-known names of early travellers, historians, and philosophers with their commentaries on widows, compulsory or non-mandatory prolonged mourning, voluntary or prescribed chastity, and a surprisingly common choice of suicide as the best option for her. Amazingly many widows obediently followed their husbands to death. In all continents, monuments and documents witness how women joined dead men—buried or burnt alive, hanged, strangled or beheaded, drowned, stabbed or shot. A preference for strangling was inspired by the idea that the victim would enter the next world ‘intact’. So, from the narrow diving board of no more than a few dozen proverbs I plunged into the hidden history of widowhood for about three years.

How do women perpetrate the victimisation of widows? Would you say that widows as a group are more victimised against than other groups of women?

Conceptions about women as interchangeable objects were widespread. If a woman was ‘no longer of use’, a man would need to get a new one, much as you would do with a broken watch, rifle, knife or whip. A man cannot or will not do without a wife, but what about when the tables are turned? The need to present women without husbands as inept and dependent must have been great. A widow managing all by herself was rather met with obvious disapproval. Widowhood has traditionally been associated with emptiness. In Sanskrit, the word vidhua means ‘destitute’, and the Latin viduata (‘made destitute, emptied’) is the root of the word for widow in many European languages, including Witwe (German), veuve (French) and weduwe (Dutch).

Nonetheless there have always been plenty of widows who have lived wonderfully independent lives, but this is not the image seared into the public consciousness. The notion that a woman is unable to live her own life after the death of her husband is an amazingly deep-rooted one. The Japanese word for widow (mibōjin) literally means ‘she who has not yet died’, that is, a widow is simply sitting in Death’s waiting room for her own time to come. Interestingly, the status of widower on the other hand was usually so short-lived and temporary that some languages even lack a word for it all together!

What makes widows more vulnerable than others?

Every widow has her own story, but social systems play an important role. In traditions where goods, land and property are inherited through the mother’s family line with matrilocality, a groom comes to live with his bride’s family, although this often ended up working out slightly differently as men were not best pleased with this living arrangement, so in reality there would be negotiation. However, over the centuries patrilineal systems, lineage and inheritance significantly became the dominant system. According to the patrilocal rules, a man had to remain ‘at home’, a system which to this day obliges countless brides to move in with their parents-in-law, an environment foreign to them. They are forced to comply with the demands and expectations of their family-in-law, while the husbands remain comfortable in the familiar surroundings they grew up in, with major consequences for the lives of women who become widows. This patrilocal living situation has often resulted in greater inequality between marital partners and harsh rules for widows, often preventing a wife from any material heritage after her husband’s death. According to the work of evolutionary psychologists, married women who live with or in close contact with their matrilineal family run a significantly lower risk of violence in the form of (physical) abuse, rape and exploitation than those who move in with their husband’s family. This is all the more true for a widow with a distrustful family-in-law who accuse her of killing her husband, a danger that is greatest in areas where poverty reigns.

At a point you have said, “The Aryan period, which preceded later negative social developments, saw a differently structured society in which there was more space for women: to a certain extent women had religious autonomy, they were entitled to education at all levels (with some even becoming celebrated authors), they participated in public life and also held important positions… However, by the year 200 AD, their position had considerably worsened.” Do you have any idea why their condition worsened in India? What were the ‘negative social developments’ you mention?

In matters of religion the woman was increasingly dependent on the services of her husband or of priests, possibly also on her sons or male relatives, to carry out the rituals she required. Simultaneously she became largely excluded from all types of formalised education. This lasting effect can be seen even today in the global difference in the rate of female and male literacy. The negative stance towards women in India dates back to Brahmin commentaries of ancient Vedic texts, which referred to women as lesser humans; widows subsequently occupied an even lower rung on the social ladder and were forced to work hard towards their religious salvation through extreme asceticism. One example: ‘At her pleasure [after the death of her husband], let her emaciate her body by living only on pure flowers, roots of vegetables and fruits. She must not even mention the name of any other men after her husband has died.’ (Manusmriti Kamam 5/160) Patriarchal relations have developed gradually in different parts of the world and at different times, but not everywhere in the same rigorous forms.

In the Abron-Kulango culture in the northeast of his native Côte d’Ivoire, you have told us “[B]oth widows and widowers were required to accompany their spouse to the next world” but eventually due to societal realisations, such practices stopped. Do you think this can happen in other cultures too. Have you seen it happen in other cultures?

As far as I know, such practices do not exist anywhere anymore. The most problematic obstacle for the rights of widow’s in less-well off regions is the unfortunate combination of illiteracy, fear of witchcraft and covetous in-laws, particularly during periods of mourning and grief. The good news is that even in the most unexpected places initiatives are emerging to help inform women in rural areas of their equality before the law. Self-aware widows become inspiring role models; conscious of their rights, they share their knowledge with others so that more of their fellow widows can find the right legal aid when injustice rears its head.

Would you hold as culprit people who enforce the death of widows? Would you address these people too as criminals in today’s context? Please elaborate.

It wouldn’t help much to do this! Marriage is still frequently presented as the utmost peak that a woman can achieve during her life. From this supposed top spot married women often still look at single and widowed women in a new light—with pity, contempt, suspicion or even hostility: they are out to seduce your own husband! When death comes calling, not only men’s but also women’s negative feelings easily bubble up from the morass of fear at the dreaded prospect of becoming a widow. Over the centuries such reactions towards widows have become part of the constrictive hierarchy meant to keep so many women in their place.

Can sati be justified [1](even though they are deemed illegal as is suicide) by saying the widow immolated herself willingly? Please explain.

The social pressure on widows must have been immense, but we are living now and no longer in the past. It is true that in poorer regions far out of the reach of cities, countless numbers of widows still have to traverse a long road towards a humane and dignified existence. However, instead of justifying the willingness to immolate herself as her own choice, it is better to insist on the positive news that, after the loss of their partner, today not only men but also women have the right to stay alive and further explore their own talents and new possibilities.

You have told us dowry started as a European custom. Is it still a custom there as it is in parts of South Asia, even if deemed illegal? Was it brought into Asia by Aryans/colonials or a part of the culture earlier itself?

The dowry is the gift that the bride’s family would contribute to the couple’s new home. Even though colonisation may have reinforced this ancient custom, but in many communities, it was already a custom and still is in many parts of the world. In Europe it stayed on until the late nineteenth century. In cultures where the bride provided a dowry, the death of a wife would bring benefits to a widower, as a new wife with a new dowry would enrich his home with new assets such as silver tableware, jewellery, bed linen and other valuables. For centuries, among Christians, divorce was forbidden, and from the perspective of widowers the prospect of a second chance provoked a sense of euphoria, as expressed in quite some sayings where his sadness does not go beyond the front door. Across Europe such messages confirm a husband’s profit of his wife’s death: ‘Dead wives and live sheep make a man rich.’ (French; UK English). However, most widows were denied such liberating feelings or didn’t experience any profit from the change. Often, they did not even allow themselves to get over her loss and indulge in any new freedom. They usually were subject to the paralysing fear of other people’s gossip.

In many places a widow who remarried would even lose entitlement to her own dowry or other input she had contributed to her marriage. Many women who remarried felt unable to invoke any right they had on the property of their deceased husband. Little wonder, therefore, that widows were heavily discouraged from remarrying, for example in China. The use of far-reaching laws still re-enforced the highly recommended chaste and sexless existence of widows after the death of her husband. Of course, the considerable number of child marriages in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia easily robbed child widows from the legal rights wherever they had. According to the World Widows Report, the situation for widows with children is still exceptionally alarming in many parts of the world. Daughters, in particular, remain a huge problem in traditions where women have to contribute a dowry when daughters get married. For this reason alone, poorer parents have a preference for sons: they are more likely to inherit from their father’s family, while their widowed mother can expect little.

Has the condition of widows across the world improved over time? Please elaborate.

Over the centuries far too many widows have been convinced that their only future was conditioned by their dead husband. In my book there are examples from different areas of courageous widows who changed their own lives. Looking around in one’s own neighbourhood, there are always exemplary models of independent widows who do not let themselves be deterred by the doom of whatever prejudiced people think or say.

All emancipation starts with the opportunity to acquire knowledge, but if we are to believe what tradition tells us, women had little need for that, based on an assumption that knowledge did nothing to encourage and promote female obedience, and even less for virtue. ‘Knowledge goes before virtue for men, virtue before knowledge for women’ is an old saying in Europe, while a Chinese saying also agrees that a woman without knowledge is already doing very well. The fact that this message has had such a wide-ranging effect can be seen in the vast difference in levels of education and training among boys and girls in global education statistics.

What did a man look out for when it came to finding a wife? In order to facilitate control over women, various warnings have been passed down to men. One such proverb found the world over clearly expresses this sentiment: ‘Never marry a woman with big feet.’ It comes from the Sena language in Malawi and Mozambique. In China, India and other parts of the world, I came across literal iterations of this proverb. In spite of geographic or cultural distances and differences, this saying reflects a widespread consensus: hierarchy in male-female relations seemed to be essential, and someone had to be in charge. Should he become the main breadwinner for the duration of their married life, his wife will be even more dependent on him.

Significantly the big feet metaphor points to male fear of female talents and power. Hardly surprising therefore that becoming a widow was the worst possible catastrophe for women. Worldwide the solidarity between wives and widows is growing and literacy support within local communities as well, while the former unwavering prejudices against widows are shrinking, and more and more widows with big feet do manage. The old anti-widow stronghold of local prejudice is slowly but surely crumbling into ruins. We cannot change history, but widows can look to the past with new knowledge and into the future with new eyes and new hope.

Thank you Mineke for your time and book.

Click here to read an excerpt from Widows

[1] https://theprint.in/ground-reports/sati-economy-still-roars-in-rajasthan-youtube-as-jaipur-court-closes-roop-kanwar-case/2331357/

(This review/interview has been written/ conducted by Mitali Chakravarty.)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International