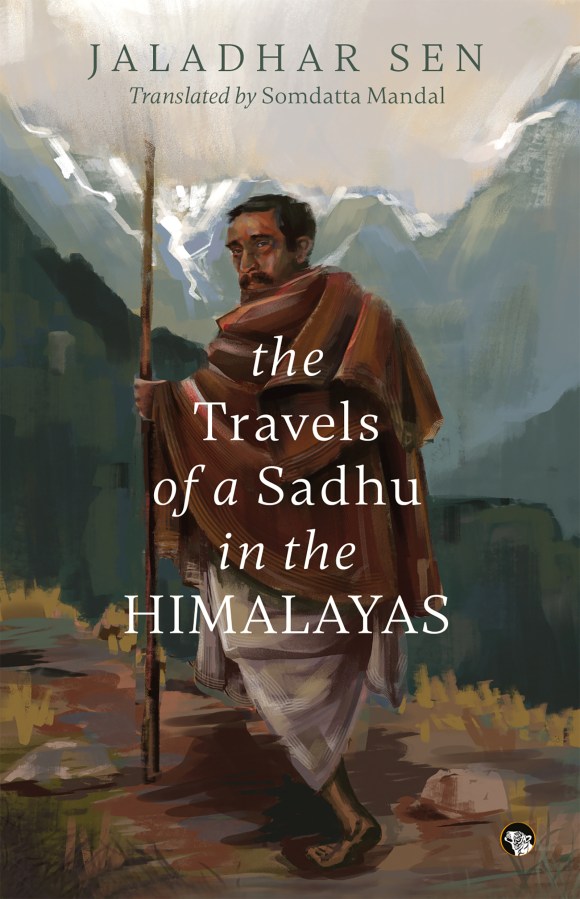

Title: The Travels of a Sadhu in the Himalayas

Author: Jaladhar Sen

Translated from Bengali by Somdatta Mandal

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

.

6th May, Wednesday

I had arranged to leave at half past four in the morning; my friends arrived even earlier to bid me farewell. It was a moonlit night, and the entire world lay silent and still. Could this small change in my life affect the grand workings of the earth? I was leaving everyone behind; friends and relatives accompanied me for quite some distance. It was evidently difficult for them to sever the affectionate ties they had nurtured with me for so long. I requested that they not proceed further; in the end, they reluctantly turned back. I, too, glanced back several times to take one last look at them. I couldn’t help but wonder—if this separation from friends was so painful, how much more difficult would it be to part from one’s own family?

A few days ago, I had read Pilgrim’s Progress*, and one scene from the book kept recurring in my mind. As we walked, my thoughts wandered to such reflections. Soon, the sun rose. We began moving towards Hrishikesh. This was an unfamiliar route—rarely travelled by others. After crossing several mountains and forests, we arrived at a small village called ‘Khanu’† around 11 a.m. This peaceful village with only five to seven houses nestled beneath a canopy of trees, resembled a tiny bird’s nest. A small stream meandered near the village. We went and took shelter under a tree by the stream, and, parched and famished, we gratefully drank its water to our hearts’ content. After eating our meal there, we resumed our journey around 5 p.m.

After leaving the village, we noticed two monks walking ahead of us. Since it was just the two of us travelling, I thought, why not join these holy men? At least the four of us could travel together for a while. We quickened our pace, but when we caught up to the two sanyasis, I felt a mix of amusement and irritation. One of them turned out to be my former servant, whom I had dismissed twenty or twenty-five days earlier for theft. His transformation was remarkable—dressed in the elaborate robes of a sanyasi, with tangled hair and constant chants of ‘Har Har Bom Bom’, he was barely recognisable as the thief he once was. It was sheer bad luck on his part that our paths crossed that day.

I recounted the whole story to Swamiji, who commented, ‘Perhaps his companion has some money in his jhola, and he has disguised himself in this manner to swindle it.’

Indeed, there seemed to be no limit to the number of people who cloaked themselves in saffron robes, with matted hair and a kamandalu, only to engage in theft, deceive innocent people, or even commit heinous crimes when the opportunity arose. Readers will encounter many such so-called sadhus in my travel narrative.

At first, my servant seemed confident I wouldn’t recognise him in his new guise. He appeared smug, believing that his ‘western intelligence’ would outwit my ‘Bengali intellect’. Seeing us, he began chanting ‘Bom Bom’ even louder, as if to reinforce his act. Unable to tolerate his pretence any longer, I burst out laughing and said, ‘Aare lounde, kabse chori chhod ke sadhu ban giya?——Oh, you scoundrel, since when did you give up thievery to become a monk?’

He was utterly stunned and rendered speechless by my words. I then explained everything to his companion, a naïve and well-meaning man. This stout young fellow had accepted my servant as his disciple, feeding him well in exchange for a few religious sermons. I said, ‘Sadhu, you may keep him and feed him—I have no objection. But if you have any money in your jhola, guard it carefully. If a man can become a sadhu in ten or twelve days, there’s nothing stopping him from becoming a murderous dacoit in a few hours.’

Later, I heard that the sadhu heeded my unsolicited advice.

By evening, we reached Bhogpur. This village was home to many people, and the presence of small brick houses suggested that some wealthy residents lived there. Close to the homes of these affluent villagers stood a dharamshala, built and maintained by the villagers themselves. Travellers and sadhus from afar could find shelter here, with food and amenities provided by the locals. However, if a traveller carried money or the village had a shop, they need not rely on these dharamshalas.

There is a great deficiency of dharamshalas in Bengal. In many respects, we are far more developed and civilised than people from other parts of India; however, we are so preoccupied that we do not have the leisure to spare time for travellers or sick people who might perish on their journeys. Of course, it must be acknowledged that there are still a few among us who are exceptions to this. Nevertheless, I feel that the uneducated Garhwali farmers, who help others, offer shelter to the distressed, and wholeheartedly care for guests, are far more sincere than the educated people of Bengal.

We spent the night at the dharamshala in Bhogpur. Exhausted from the rigours of travelling, we had no need for food and instead went straight to sleep.

7th May, Thursday

We resumed our journey early in the morning and entered the forest of Hrishikesh, which we had traversed before. Although the forest was familiar, the path was entirely unknown; we could not determine whether we were following the same route we had previously taken. We reached Hrishikesh at 1 p.m. and rested beneath a tree, still without any food. Once the afternoon sun’s glare had lessened, we resumed our journey and reached Lakshman Jhula by evening.

The few shops overlooking the Ganga at Lakshman Jhula were bustling with travellers. A group of Udasi sanyasis had arrived that very day. They were Sikhs.

(Excerpted from The Travels of a Sadhu in the Himalayas by Jaladhar Sen, translated by Somdatta Mandal. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2025.)

THE BOOK

In the summer of 1890, Jaladhar Sen left behind a life of domesticity and embarked on an adventure across some of India’s most sacred landscapes, from Hrishikesh, all the way to Badrinath. Armed with little more than a blanket, a staff, and a book of songs by the renowned Bengali poet and Baul singer Kangal Harinath, he journeyed through perilous mountain passes, snowbound valleys, and remote pilgrim towns—seeking not the divine, but solace for a life fractured by loss.

Sen’s deeply personal travelogue chronicles the breathtaking beauty of the Himalayas—the roaring Alakananda, the towering peaks of Nara and Narayan, the spiritual might of Shankaracharya’s Joshimath, the bustling markets of Srinagar, and the ethereal stillness of Badrinath—along with a vivid cast of characters—from stoic sadhus, cunning pandas and officious police personnel to ailing young boys, large-hearted villagers and even fellow Bengali pilgrims. In the shadow of the Himalayas, Sen reflects on the complexities of faith, the hypocrisies of ascetic life, and the profound tenderness of human connection.

Blending diary observations and literary flourish, Himalay—first published in 1900—had once captured the imagination of a generation of Bengalis, inspiring them to travel far beyond their homeland. This English translation reintroduces Sen’s compelling account to a new audience, highlighting its historical importance and enduring charm as one of the earliest modern Bengali narratives of the Himalayan experience.

THE AUTHOR

Jaladhar Sen (1860–1939) was a Bengali writer, poet, editor and a philanthropist, traveller, social worker, educationist, and littérateur. He was awarded the title of ‘Ray Bahadur’ by the British Government. In 1887 he suffered the greatest loss in his life when his mother, wife and daughter died in quick succession. Overwhelmed by grief and seeking solace, Jaladhar moved to Dehradun at the foothills of the Himalayas, where he worked as a teacher. It was during this time, in 1890, that he travelled to the Garhwal Himalaya. This journey inspired his travelogue Himalay.

THE TRANSLATOR

Somdatta Mandal is the Former Professor of English and Chairperson at the Department of English & Other Modern European Languages, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan. Somdatta has a keen interest in translation and travel writing.

Read an interview with a the translator and a review by clicking here

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL