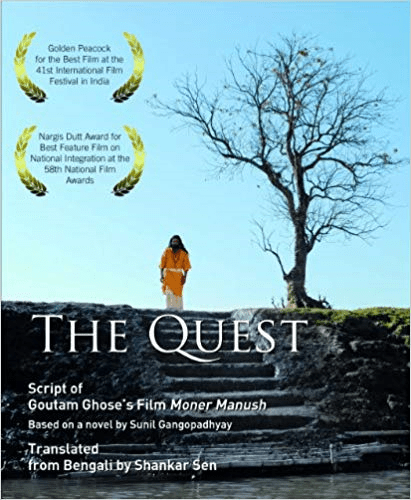

A discussion with Nazes Afroz along with a brief introduction to his new translation of Syed Mujtaba Ali’s Tales of a Voyager (Joley Dangay), brought out by Speaking Tiger Books.

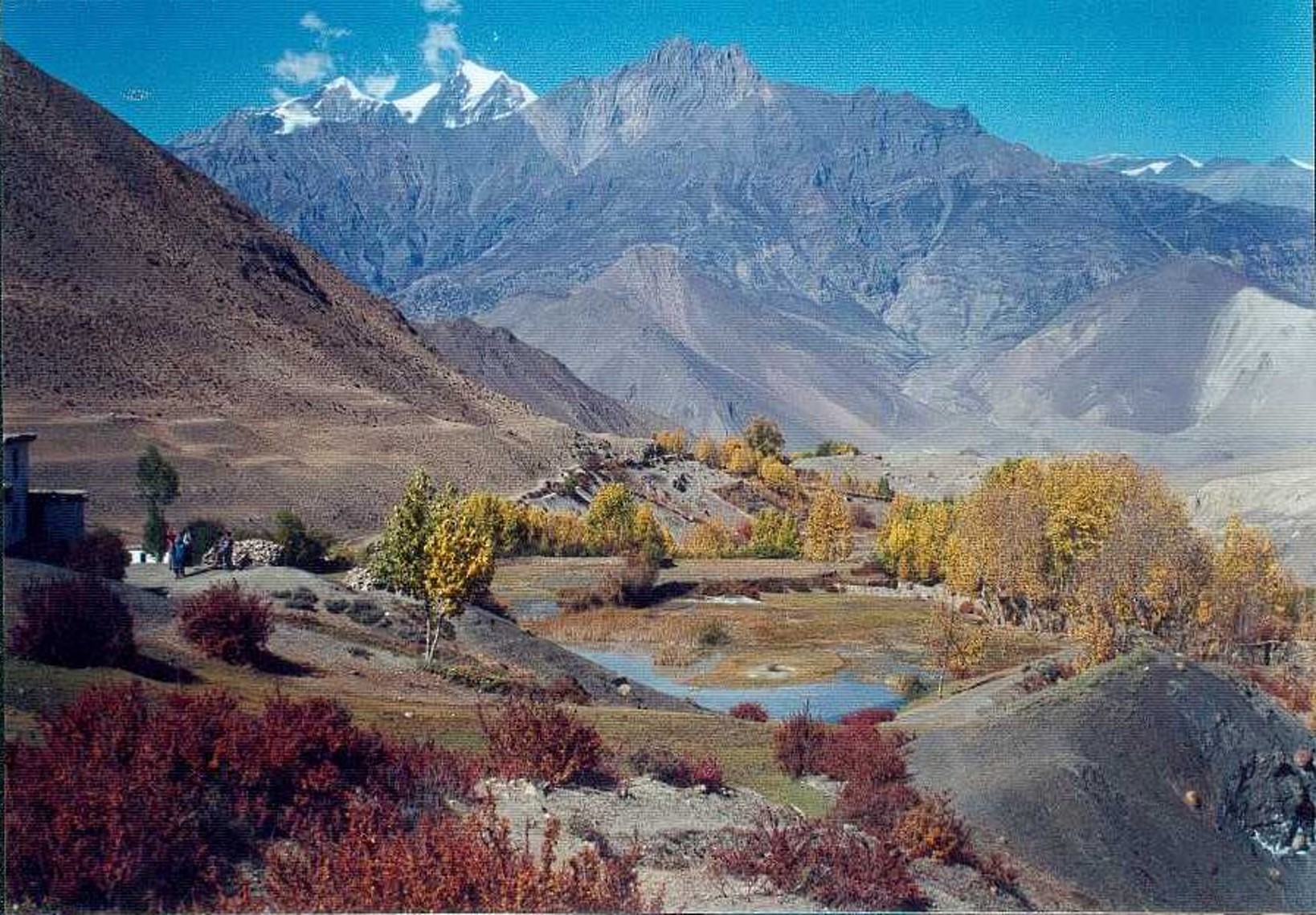

Translations bridge borders, bring diverse cultures to our doorstep. But here is a translation of a man, who congealed diversity into his very being — Syed Mujtaba Ali (1904-1974), a student of Tagore, who lived by his convictions and wit. Like his guru, Mujtaba Ali, was a well-travelled polyglot, who till a few years ago was popular only among Bengali readers with his wide plethora of literary gems that can never be boxed into genres precisely. People were wary of translating his witty but touching renditions of various aspects of life, including travel and history from a refreshing perspective, till Nazes Afroz, a former BBC editor, took it up. His debut translation Mujtaba Ali’s Deshe Bideshe as In a Land Far from Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan in 2015 was outstanding enough to be nominated for the Crossword Prize. Recently, he has translated another book by Mujtaba Ali, Tales of a Voyager (Joley Dangay[1]), a book that takes us back a hundred years in time — a travelogue about a sea voyage to Egypt and travel within.

This narrative almost evokes a flavour of Egypt as depicted by Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile (1937) or The Mummy (film, set in 1932), simply because it is set around the same time period. Afroz in his introduction sets the date of Mujtaba Ali’s travels translated here between 1935 and 1939. The book was published in 1955. This book is a treasure not only because it gives a slice of historic perspective but also weaves together diverse cultures with syncretism.

Mujtaba Ali has two young travel companions, Percy and Paul, who despite being British (one of them is on the way to study in Oxford) seem to have a fair knowledge of Indian lore and there is the inimitable Abul Asfia Noor Uddin Muhammad Abdul Karim Siddiqi, who almost misses a train while trying to argue about the discrepancies shown in the time between his Swiss watch and the clock at Cairo. The description is sprinkled with tongue-in-cheek humour.

The voyage starts at Sri Lanka and sails through the Arabian Sea to Africa, where the ship pauses at Djibouti. Here, Mujtaba Ali expands his entourage with the addition of the long-named Abul Asfia, well-described in the blurb as a man who “carried toffees, a gold cigarette case, and other sundry items in his capacious overcoat pocket and who had the answer to all problems though he barely spoke a word ever.” Afroz himself has given an excellent introduction to the writer and the book — almost in the style of Mujtaba Ali himself. This is a necessary addition as it highlights Mujtaba Ali’s perspectives and gives his background to contextualise the relevance of this translation.

Mujtaba Ali’s style is poetic and humorous. It demystifies erudition and touches the heart simultaneously. His ability to laugh at himself is inimitable. He tells us a story about how the giraffe from Africa was introduced to China by a king from Bengal. At the end, he and his companions reflect about the tallness of this tale!

Mujtaba Ali contends: “‘…One of my friends is learning Chinese in order to read Buddhist scriptures in that language. Possibly you know that many of our ancient scriptures were destroyed with the decline of Buddhism in India. But they are still available in Chinese translations. My friend came across this story while searching for Buddhist scriptures. He had it translated and published in Bengali with the copy of the painting in a newspaper. Or else Bengalis would never have known of this because there is no mention of it in our history books or documents in the archives in Bengal.’”

The irony is not lost that Buddha is of Indian origin and yet an Indian has to learn Chinese to read the scriptures. The narrative continues with more dialogues:

“Percy said, ‘But sir, it didn’t sound like history. It [the giraffe’s story] exceeds fiction.’

“I [Mujtaba Ali] replied, ‘Why, brother? There is the saying in your language, ‘Truth is stranger than fiction.’

“And my personal opinion was that if the narrative of an event could not rouse interest in someone more than fiction, then that event had no historical value. Or I would say that the narrator was not a true historian. In our land, most of our historians are such dry bores.”

As Mujtaba Ali’s renditions are colourful – is he a ‘true historian’ by his own definition? Such narratives dot the travelogue, generating curiosity about major issues in a light vein and linking ancient cultures with the commonality of human needs, creating bridges, taking us to another time, finding parallels and making learned, hard concepts comprehensible by the simplicity of his observations.

Similarly, he says of the rose: “The Mughal-Pathan era of India ended a long time ago, but can we say for how long the roses brought by them will continue to give us fragrance?”

Some of his renditions are poetic and beautiful. Mujtaba Ali watches the sunrise by the pyramids and describes it: “Streaks of light were gradually lighting up the liquid darkness. The white parting in the middle of black hair was becoming visible. There was a light daubing of vermillion on that.”

Borrowing from diverse cultures, Mujtaba Ali skilfully weaves the commonality of cultures, customs and countries into his narrative under the umbrella of humanity. Afroz with his journalistic background and a traveller himself, is perhaps the best person to translate this narrative of another traveller from the past. The depth of erudition simplified with humour has been well captured in this translation too. In this interview, Afroz discusses more about the author, his new translation and the relevance of the book in the present context.

You have translated two books by Mujtaba Ali. Is he essentially an essayist? Were there many essayists and travel writers at that point, especially from within Bengal? Where would you place him as a writer in the annals of Bengali literature?

I don’t think that ‘essentially an essayist’ is the right description of Mujtaba Ali. Of course he wrote many essays but his repertoire included novels, short stories, funny anecdotal pieces based on his experiences (in Bangla they are called romyorochona) and stories from his travels, his encounters with extremely interesting people across the globe. He was deeply interested in culinary experiences. So he wrote a lot about food habits, multitude of cuisine and also gave recipes. Hence, it is difficult to box him into one genre of writing. With the publication of his first book, Deshe Bideshe, (serialised in 1948 in Bangla literary magazine Desh and as a book in 1949) he instantly occupied a significant place in Bengali literature.

His Bangla prose, steeped in effortless and seamless multilingual and multicultural references, swept the discerning readers of Bangla literature off their feet. It was not only the prose that he created but the breadth and depth of subjects his pen touched was unparalleled. No author in Bangla language has been able to write on such a wide range of topics till date.

Coming to the other part of the question about travel writers and essayist in Bengal in early part of the twentieth century: the short answer is, yes there were many. Travel writing has been an important genre in Bangla literature. Bengalis had been travelling – for pilgrimage, for rest and recuperation following illnesses, or just for pleasure since the middle of the nineteenth century, which was the time of Bengal renaissance. Writers who undertook such journeys, wrote about their travels too. So Mujtaba Ali is no exception in that regard. He followed in the footsteps of his predecessors and also his peers.

You have called the book ‘Tales’ of the Voyager — would you say that some of the stories are like tall tales here — perhaps tales to convey an idea or a thought which in itself would be larger than history in explaining the truth of a civilisation, like the tale of the giraffe? Would you see this as a comment on the gap between popular and documented narratives in history and on the different interpretations of history?

Ali was an excellent raconteur. He was also gifted with an almost eidetic memory. This allowed him to learn a dozen languages – some with native proficiency. He was a voracious reader too. So, not only did he read tomes on history and philosophy in many languages across cultures but also he gathered fascinating tales from many corners of the world as he loved storytelling. Whenever opportunities came, he masterfully wove those stories into his writing. Thus the tale of the giraffe’s journey from Africa to China via Bengal found its way in this book as he was narrating stories from the east coast of Africa. There is another thing that makes Ali’s writing attractive. He weaves in fascinating quirky funny stories while discussing something apparently dense and dry. I have not come across many writers who have done that. I don’t know whether to name it as his comment on bridging the gap between popular and documented history. There’s no evidence to prove that he was trying to achieve that as he never mentioned it. We could only conclude that it was a style that he invented and mastered in an effort to engage with his readers.

A writer that came to mind while reading this book of Mujtaba Ali is, one who is really more entertaining than accurate –Marco Polo. We know he lived five centuries before Mujtaba Ali. Mujtaba Ali of course is erudite, a scholar, but he seems to have a similar fire within him, a wanderlust. Do you think he would have been impacted by the writings of Marco Polo? Was wanderlust not a very typical phenomenon that was part of the culture that had evolved in Bengal post the Tagorean renaissance? Did Mujtaba Ali also travel for wanderlust?

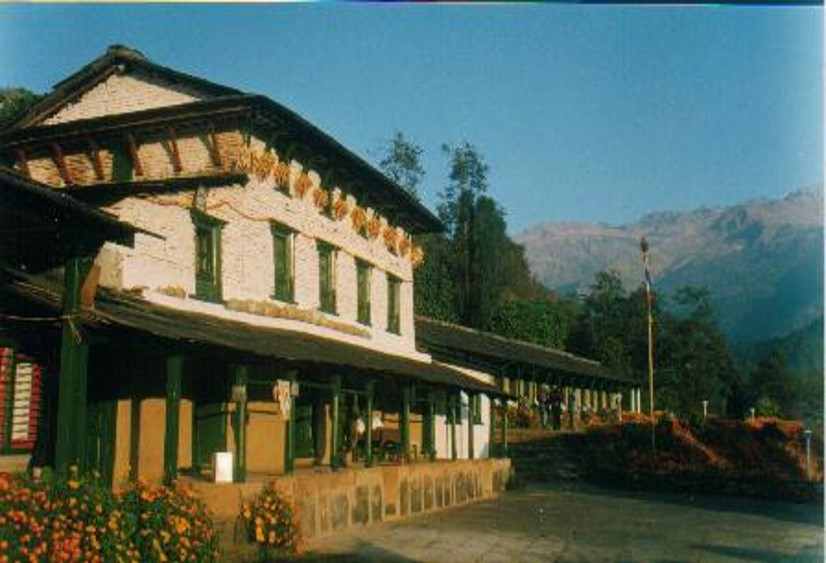

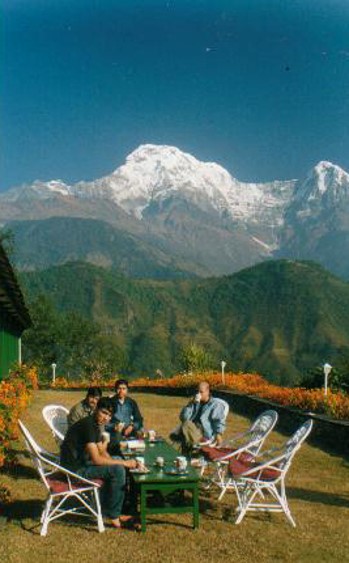

Reading Ali’s books, one may think that he had wanderlust in the true sense. It will be correct to assume that he was fidgety; he refused to settle down; he moved jobs; he moved cities and even continents. But to be truly smitten by wanderlust, one has to enjoy the travel, which wasn’t possibly the case for Ali. His son told me that even though he travelled extensively, Ali didn’t enjoy travelling much. There had been many, of his time, who were really smitten by wanderlust — like Rahul Sankrityayan (1893-1963, walked to Tibet twice and wrote only in Hindi), Bimal Mukherjee (1903-1996, a true globetrotter who cycled to London from Kolkata), Umaprasad Mukhopadhyay (1902-1997, who crisscrossed the Himalayas from one end to another), Probodh Kumar Sanyal (1905-1983, his travelogues of the Himalayas), Premankur Atorthi (1890-1964, author of Mahasthobir Jatok) — to name a few. While these authors were inherently bohemian and were drawn towards travelling only for the sake of it, Ali was more of an unsettled soul who travelled with a particular purpose and wrote about his experiences as he had picked up fascinating stories and observed connections between cultures. Because he loved to tell stories and also because he was infused with the idea of internationalism that he inculcated from Tagore, there was no way he could escape but narrating the stories and cultural experienced from his travels.

Tales of a Voyager takes us on a sea voyage to Egypt. Did you travel to Egypt while translating the book? Would you say that the Egypt of those times still resonates in the present day — especially after the 2011 uprising?

Even before his one night stopover in Cairo that he narrated in Tales of a Voyager, Ali had previous experience of Cairo where he spent a year as a post-doctoral scholar in 1933-34 at the Al-Azhar University. So there are many short pieces on Cairo and Egypt by him in his other books. He raved about the café-culture of Cairo and came to the conclusion that Egyptians surpassed the Bengali in terms of adda—hours of the purposeless sessions of chitchat and chinwag. I have been to Cairo at least half a dozen times and realised how acute his observation was. I witnessed in person why Ali mentioned that this was a city that never slept. The cafes and shops were open all night and the streets were full of people with families including children until well past midnight.

As expected, the political landscape that you mention in the question, would be completely different between Ali’s time in the 1930s and in 2010 when I started visiting Cairo. When Ali first went to Cairo in 1933, Cairo had just gained full independence from the forty years of British occupation (not as an annexed state but more of a protectorate). So there are some references of the political figures like Sa’ad Zaghloul Pasha[2] in his various writings but the main focus was on its cultures.

When I started travelling to Cairo from 2010, I witnessed some similarities in the cultural traits as elaborated by Ali. But politically by then, Egypt had moved far from where it was in the 1930. It had become an architect of the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1950s. It was the most prosperous country in North Africa and an important leader among the Arab nations. But it was also reeling under the oppression of one party rule and the youth were bubbling to break away from that. This is something we witnessed unfolding from 2011.

What were the challenges you faced while translating this book? Was it easier to handle as it was the second book by the same author?

The main challenge of translating Mujtaba Ali is transposing his unique language steeped in multi-lingual references into English. Also to get his oblique sense of wit and puns from Bangla into another language, which at times, may not have the right words for them. Translating the second book of the same author doesn’t make it easier as the challenges I just mentioned remain for every book.

Tell us what spurs you on to continue translating Mujtaba Ali. Please elaborate.

Syed Mujtaba Ali’s writing had a huge influence on me from my young age. His writing shaped my worldview, planted the seeds of curiosity about many societies, taught me how to make friends in distant lands and start making connections between cultures. So what I’m today is largely due to his writing. As an avid reader of his texts, I felt that it was my duty to introduce him to a wider readership. That’s the motivation of my taking up the translation of Ali. It is also a tribute to a writer who had such an impact on me.

In your introduction you have written of Mujtaba Ali and his writing. What had he written to be put on the Pakistani watchlist in 1950s?

He had penned an essay opposing the imposition of Urdu as Pakistan’s national language on the Bengalis who were in majority in the newly created East Pakistan. He even predicted how the Bengalis would rebel against such a policy, which came true in 1952 in the form of the Language Movement. He wrote this when he was the principal of a government college in Bogura. So he drew wrath of the Pakistani leaders and an arrest warrant was issued against him. That was the time when he left Pakistan and returned to India in 1949.

There also the other difficult personal situation. His wife (married in 1951) who was from Dhaka and was working in the education ministry, continued to live in East Pakistan with their two sons while he lived in India working for the Indian Government. So Pakistanis always thought he was an Indian spy while he was under suspicion in India that he was on the side of Pakistan!

Did Mujtaba Ali participate in the political upheaval between Pakistan and Bangladesh? Please elaborate if possible.

Ali was hugely affected in 1971 because of his personal situation as I just mentioned. I don’t know how deeply he was involved with the liberation war in Bangladesh but he wrote a novel, Tulonaheena (his last novel), against that backdrop – based in Kolkata, Shillong and Agartala and told through the story of a lover couple – Shipra and Kirti. So it is likely that he was involved in some capacity with the war efforts.

Mujtaba Ali studied in Santiniketan — that would have been in the early days of the university. Would he have been influenced by Tagore himself and the other luminaries who were in Santiniketan at that time? Can you tell us how? And did that impact his work and outlook?

The simple answer is: it was huge. Tagore was the polar star for Mujtaba Ali, which he acknowledged every now and then in his writing. This experience also decided his life’s journey. He imbibed humanism and internationalism as a direct student of Tagore in Santiniketan. He also developed deep apathy towards all sorts of bigotry. So it was not surprising that he would find it very difficult to accept a country that was created on the basis of religion.

Do you find him relevant in the present-day context? Is your writing influenced or inspired by his style?

I feel that his relevance will never fade. His ability to create cultural connection from different corners of the world will continue to fascinate readers for generations. Yes, in this globalised world when information from around the world are at our finger tips with the click of a button but one also needs to learn how to look at those information beyond mere facts and go deep underneath to make a sense. Apart from being fun and entertaining read, I feel his writing is one such training tool to learn how to make cultural connections. This way, if one wants, one can truly become a global citizen.

As for me, my outlook towards the world is massively influenced by Ali’s writing but not my writing style. It’s simply because I’m not a polyglot like him! I’ll not be able to come anywhere close to his style even if I try.

Well, that is for the reader to judge I guess! You have books on Afghanistan. But you do travel with your camera often. Will you write of your own travels at some point — like Mujtaba Ali but in English?

I have only one book on Afghanistan – a cultural guide book that I co-authored with an Afghan friend. I was working on my own book on Afghanistan, which would have capture one decade of Afghan history and interspersed with my own direct experiences of the country between 2002 and 2015. But the research got stalled for lack of funding. I hope to revive it at some point. And, yes I would like to do my own writing from my travels. That’s there in the wish list.

What are your future plans as a journalist, writer and photographer?

Travel more, see the world more, make more friends and photograph more!

Thanks a lot for giving us your time and the wonderful translation.

[1] Literal translation from Bengali, In Water and On Land

[2] 1857-1957, Egyptian revolutionary and statesman

Read the excerpt from Tales of a Voyager by clicking here

(The online interview has been conducted through emails by Mitali Chakravarty)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International