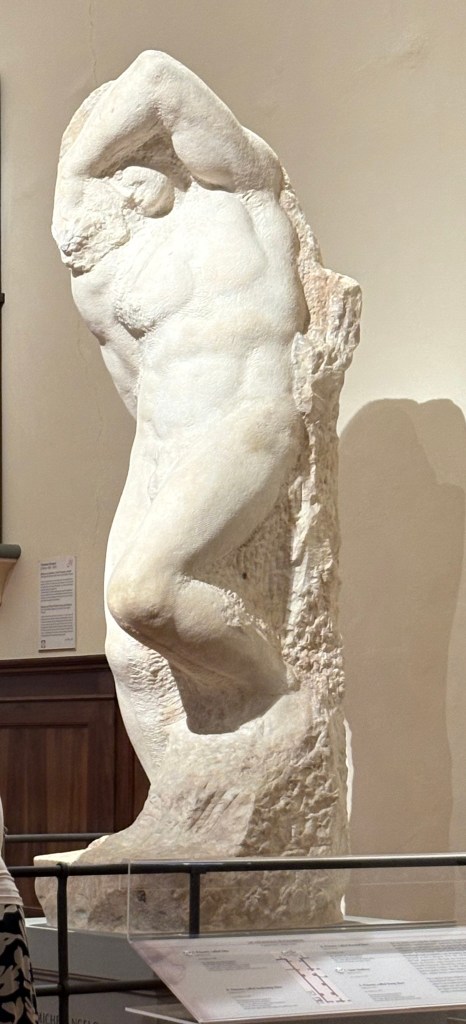

In the Accademia Gallery, Florence, are housed incomplete statues by Michelangelo that were supposed to accompany his sculpture of Moses on the grand tomb of Pope Julius II. The sculptures despite being unfinished, incomplete and therefore imperfect, evoke a sense of power. They seem to be wresting forcefully with the uncarved marble to free their own forms — much like humanity struggling to lead their own lives. Life now is comparable to atonal notes of modern compositions that refuse to fall in line with more formal, conventional melodies. The new year continues with residues of unending wars, violence, hate and chaos. Yet amidst all this darkness, we still live, laugh and enjoy small successes. The smaller things in our imperfect existence bring us hope, the necessary ingredient that helps us survive under all circumstances.

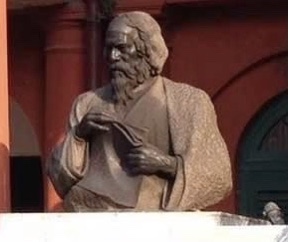

Imperfections, like Michelangelo’s Non-finito statues in Florence, or modern atonal notes, go on to create vibrant, relatable art. There is also a belief that when suffering is greatest, arts flourish. Beauty and hope are born of pain. Will great art or literature rise out of the chaos we are living in now? One wonders if ancient art too was born of humanity’s struggle to survive in a comparatively younger world where they did not understand natural forces and whose history we try to piece together with objects from posterity. Starting on a journey of bringing ancient art from her part of the world, Ratnottama Sengupta shares a new column with us from this January.

Drenched in struggles of the past is also Showkat Ali’s The Struggle: A Novel, translated from Bengali by V. Ramaswamy and Mohiuddin Jahangir. It has been reviewed by Somdatta Mandal who sees it a socio-economic presentation of the times. We also carry an excerpt from the book as we do for Anuradha Marwah’s The Higher Education of Geetika Mehendiratta. Marwha’s novel has been reviewed by Meenakshi Malhotra who sees it as a bildungsroman and a daring book. Bhaskar Parichha has brought to us a discussion on colonial history about Rakesh Dwivedi’s Colonization Crusade and Freedom of India: A Saga of Monstrous British Barbarianism around the Globe. Udita Banerjee has also delved into history with her exploration of Angshuman Kar’s The Lost Pendant, a collection of poems written by poets who lived through the horrors of Partition and translated from Bengali by multiple poets. One of the translators, Rajorshi Patranabis, has also discussed his own book of supernatural encounters, Whereabouts of the Anonymous: Exploration of the Invisible. A Wiccan by choice, Patranbis claims to have met with residual energies or what we in common parlance call ghosts and spoken to many of them. He not only clicked these ethereal beings — and has kindly shared his photos in this feature — but also has written a whole book about his encounters, including with the malevolent spirits of India’s most haunted monument, the Bhangarh Fort.

Bringing us an essay on a book that had spooky encounters is Farouk Gulsara, showing how Dickens’ A Christmas Carol revived a festival that might have got written off. We have a narrative revoking the past from Larry Su, who writes of his childhood in the China of the 1970s and beyond. He dwells on resilience — one of the themes we love in Borderless Journal. Karen Beatty also invokes ghosts from her past while sharing her memoir. Rick Bailey brings in a feeling of mortality in his musing while Keith Lyons, writes in quest of his friend who mysteriously went missing in Bali. Let’s hope he finds out more about him.

Charudutta Panigrahi writes a lighthearted piece on barbers of yore, some of whom can still be found plying their trade under trees in India. Randriamamonjisoa Sylvie Valencia dwells on her favourite place which continues to rejuvenate and excite while Prithvijeet Sinha writes about haunts he is passionate about, the ancient monuments of Lucknow. Gulsara has woven contemporary lores into his satirical piece, involving Messi, the footballer. Bringing compassionate humour with his animal interactions is Devraj Singh Kalsi, who is visited daily by not just a bovine visitor, but cats, monkeys, birds and more — and he feeds them all. Suzanne Kamata takes us to Kishi, brought to us by both her narrative and pictures, including one of a feline stationmaster!

Rhys Hughes has discussed prose poems and shared a few of his own along with three separate tongue-in-cheek verses on meteorological romances. In poetry, we have a vibrant selection from across the globe with poems by Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Ron Pickett, Snehaprava Das, Stephen Druce, Phil Wood, Akintoye Akinsola, Michael Lauchlan, Pritika Rao, SR Inciardi, Jim Murdoch, Pramod Rastogi, Joy Anne O’Donnell, Andrew Leggett, Ananya Sarkar and Annette Gagliardi. Rich Murphy has poignant poems about refugees while Dmitry Bliznik of Ukraine, has written a first-hand account of how he fared in his war-torn world in his poignant poem, ‘A Poet in Exile’, translated from Ukranian by Sergey Gerasimov —

We've run away from the simmering house

like milk that is boiling over. Now I'm single again.

The sun hangs behind a ruffled up shed,

like a bloody yolk on a cold frying pan

until the nightfall dumps it in the garbage…

('A Poet in Exile', by Dmitry Blizniuk, translated from Ukranian by Sergey Gerasimov)

In translations, we have Professor Fakrul Alam’s rendition of Nazrul’s mellifluous lyrics from Bengali. Isa Kamari has shared four more of his Malay poems in English bringing us flavours of his culture. Snehaparava Das has similarly given us flavours of Odisha with her translation of Pravasini Mahakuda’s Odia poetry. A taste of Balochistan comes to us from Fazal Baloch’s rendition of Sayad Hashumi’s Balochi quatrains in English. Tagore’s poem ‘Kalponik’ (Imagined) has been rendered in English. This was a poem that was set to music by his niece, Sarala Devi.

After a long hiatus, we are delighted to finally revive Pandies Corner with a story by Sumona translated from Hindustani by Grace M Sukanya. Her story highlights the ongoing struggle against debilitating rigid boundaries drawn by societal norms. Sumana has assumed a pen name as her story is true and could be a security risk for her. She is eager to narrate her story — do pause by and take a look.

In fiction, we have a poignant narrative about befriending a tramp by Ross Salvage, and macabre and dark one by Mary Ellen Campagna, written with a light touch. It almost makes one think of Eugene Ionesco. Jonathan B. Ferrini shares a heartfelt story about used Steinway pianos and growing up in Latino Los Angeles. Rajendra Kumar Roul weaves a narrative around compassion and expectations. Naramsetti Umamaheswararao gives a beautiful fable around roses and bees.

With that, we come to the end of a bumper issue with more than fifty peices. Huge thanks to all our fabulous contributors, some of whom have not just written but shared photographs to illustrate the content. Do pause by our contents page and take a look. My heartfelt thanks to our fabulous team for their output and support, especially Sohana Manzoor who does our cover art. And most of all huge thanks to readers whose numbers keep growing, making it worth our while to offer our fare. Thank you all.

Here’s wishing all of you better prospects for the newborn year and may we move towards peace and sanity in a world that seems to have gone amuck!

Happy Reading!

Mitali Chakravarty

CLICK HERE TO ACCESS THE CONTENTS FOR THE JANUARY 2026 ISSUE.

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.