By Snigdha Agrawal

She stood somewhere at 5 feet 8 inches. Of athletic build. Swarthy skin. A face full of punch holes; ravages of smallpox during childhood. Her disarming smile more than made up for the lack of a flawless complexion. The girls were told she was being employed as their Ayah, with strict instructions to address her as ‘Didi[1]’. The Ayah affix after her name, was a ‘no’, ‘no’ in a Bengali household. So, it was Suga Didi right from day one. The rest of the elite living in the cosmopolitan community frowned upon such bourgeois sentiments.

Suga lived in a Santhal village, on a river bluff, surrounded by dense Sal Forest. Inaccessible by road and cut off from civilisation. The only Santhal village in the area, close to the gated community, offering employment opportunities to the tribals. Not that they were keen on leaving the village to work in the steel and brick factories. Suga was the one-off amongst them venturing out from her cloistered society. She arrived for the interview, hair oiled, drawn back from her face tied into a chignon, and dressed in a cotton saree with a red border, way above her ankles. The blouse was missing. Her attire would surely be viewed as improper in the elitist community. She spoke in the Santhal dialect, with words common to Bengali and Hindi. Amenable to change, she did not resist the suggestion of wearing a blouse, nor letting down the saree border to her ankles, when reporting for work. Agreed happily to the working hours from 6.30 am to 4.30 pm, five days a week. During school vacations, morning reporting was pushed back to 8.30 am.

The decision to employ Suga was borne out of necessity. With four growing girls, aged between fourteen and four, or thereabouts, it was becoming increasingly difficult for their mother to handle all the chores. Plaiting their hair, getting them dressed for school, ironing uniforms, and accompanying them to the school Bus stand, were some of the many activities entrusted to her. Add to that, the role of a luggage carrier. With four school bags, piled on her head, and four tiffin baskets weighed down with filled water bottles, hand-held, she shepherded the girls safely, morning and evening. It wasn’t an easy walk. There were open drains to cross. Heavily loaded truck movement posed a serious problem as well. She guarded them like her own. Taking care of the girls when they got home from school was also included. Occasionally, when the mood was right, she shared ancient tribal folklore, sometimes breaking into a song.

The eldest of the four had read stories of tribal practices. Witchcraft. Human sacrifice. Eating wild animals. Men and women drinking ‘mahua’ toddy. Suga was questioned on the validity of all this to which, she neither denied nor confirmed. Tribal secrets were not for the ears of the civilized. But she couldn’t ward off the pestering from the girls for long. And went on to narrate the story of the Santhal deity, Bonga, visiting their village on a moonless night, in the guise of a king cobra to drive away the bad spirits living on the edge of the forest, responsible for killing the cattle. Quietly slithering on the muddy terrain, the twelve-feet reptile, held the spirits captive, performing a wild dance with its raised hood. And then struck. The spirits screamed and fled, never to return. The village headsman invited the cobra for dinner, sharing toddy and barbequed lizards. That was not the end of the story. Suga concluded that the snake dissatisfied with the host, gobbled his head from neck upwards. The girls held onto each other shocked out of their wits. A bizarre ending. Doubts were raised as to whether the story was real or imaginary, made up by Suga Didi. Many such stories found their way into the older one’s scrapbook. Later found in the steel trunk, along with old photos, discovered by the younger two.

When Birbhadra the cook took leave to visit home, Suga filled in, helping out with cutting, and clipping the meat and fish. All the preparatory work for cooking the meals. Prepared by the lady of the house. The girls were curious to know what Suga cooked at home. Her stock answer was hot, spicy, and unpalatable. Their persistent pleading to cook a tribal dish at some point bore fruit. Reluctantly, she agreed to treat the household with a recipe, made from goat innards. The butcher supplying meat was duly informed to send the liver, fat, spleen, heart and intestines. “Eww, gross!” But not so, when the dish arrived on the dining table. Blood red with a film of fat floating on the top, garnished with freshly chopped coriander leaves. In no time it was polished off. Delicious! Delicious! All exclaimed. Suga was on cloud nine that day. They named the dish “Chagol Pagol Curry[2]”. Suga’s signature dish.

It was the spring of 1959. By then, the older girls had left for boarding school. Younger ones then six, were pretty much able to ready themselves for school on their own. Suga’s workload had halved. For most of her free time, she took upon herself the role of gardener, attending to the vegetable garden, and advising the gardener on how best to get good yields from her experience of growing vegetables in the village. The smell of ‘bidi[3]’ wafting into the porch, meant the two were sharing a smoke.

And then for over a week during that summer, she had not reported for work. Alarm bells rang in the household. Had she fallen ill? Had she died of cobra poisoning? Had she been thrown out from the village for violating the rules? Worst still, was she a victim of human sacrifice? Concerns that kept the family awake. No one knew her address, except that she belonged to the Santhal village on the river bluff, inaccessible to non-tribals. A security guard from the factory was sent to find out if the headsman could be summoned to the river, under the ruse of gifting him Scotch whiskey. Didn’t work. No one responded to the call, announced with a handheld loudspeaker. Several attempts were made to no avail. Rumours mills were churning out stories of her having eloped with the cook, Birbhadra, though it made no logical sense. Happily married with a dozen or so kids living in Begusarai, he could least afford a second wife. Though coincidentally, Birbhadra left employment around the time Suga was out of the radar.

It was decided there was no further need to employ a nanny aka ‘didi’ for the girls. Suga was the first and the last. Irreplaceable. She remains an enigma to date.

.

[1] Elder sister

[2] Crazy goat curry

[3] A type of cheap cigarette made of unprocessed tobacco wrapped in leaves

Snigdha Agrawal (nee Banerjee) is a published author of four books and a regular contributor to anthologies. A septuagenarian, she writes in all genres of poetry, prose, short stories and travelogues.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

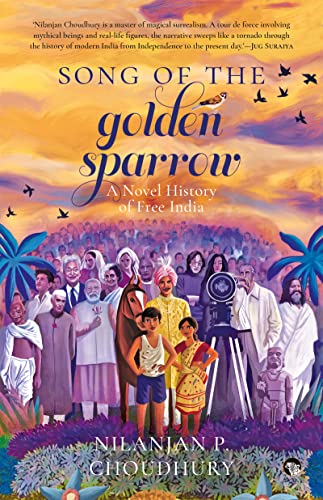

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International