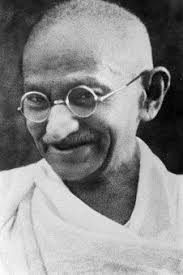

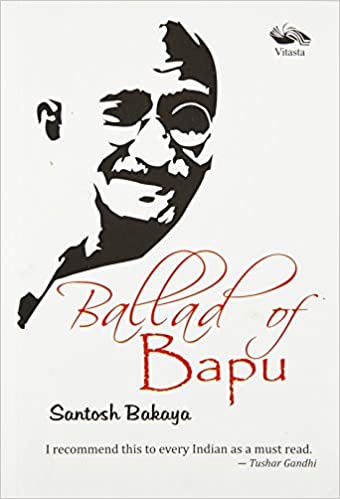

She is vivacious with what she describes as a “whacky” sense of humour and a passion for Gandhi. She has written a ballad on Bapu. You have guessed who she is – Santosh Bakaya. The thing that most impressed me about her was the way her students responded to her – students who are leading lives away from her academic umbrella even to this date. A strong influencer, who helps mould younger minds, she writes books to change her student’s lives and is a writer in her own right. Bakaya is not only an academic but a poet, essayist, novelist, biographer, editor, TEDx Speaker, and creative-writing mentor. She has been internationally acclaimed for her poetic biography of Mahatma Gandhi, (Ballad of Bapu). Her Ted Talk on The Myth of Writer’s Block, is very popular in creative writing Circles.

She has published multiple books of poetry, a novella, essays and biographies. A winner of multiple awards, her long, narrative poem, Oh Hark! which earlier figured in her book, The Significant Anthology, is now a book with illustrations by Avijit Sarkar.

Bakaya has given Borderless an extensive interview on her perception of Gandhi and Gandhism and its relevance in the current crisis filled world, punctuated with snippets of interesting vignettes from her teaching career, confirming well her characteristic of being a strong influencer in her students’ lives. Let us explore her principled, courageous and humorous outlook with her own words.

You have written a whole book and more on Gandhi. What developed your interest in Gandhi?

Gandhi, nay Bapu, was very much a part of my growing up years. My dad, (a very popular professor of English, in Rajasthan University, Jaipur), when faced by a dilemma, would invariably ask himself, what would Bapu have done in such a situation, and would go on to do what he thought Bapu would have done in that circumstance.

He never asked us to read books on Gandhi, but ignited our interest in this enigmatic man, who seemed to have an answer to everything. Was he a magician, we youngsters wondered! He would get books on Gandhi from the university library, and they would be lying at strategic points in our house; we would quietly start reading, imbibing and asking questions.

Later, it was while taking an MPhil class in the year 2012 that there was a heated discussion in the class on Bapu and his relevance. In a class of twenty students, there was just one girl who was defending the values of Bapu, the others were going all out to denigrate him.

“How much have you read on Gandhi? Can you give me the names of five books about Gandhi that you have read? Have you read his My Experiments with Truth?”

Then one student, who prided himself on being a poet, chipped in, “Madam, why don’t you write a poetic biography of Gandhi? Poetry will appeal more to us.”

This challenge hit me hard, (I am always on the lookout for challenges), but this appeared too difficult a task. Nonetheless, I took the challenge, and began by writing a few verses on the aa-bb-a rhyme scheme and got addicted, so much so that I went on to complete 300 pages of poetry on Gandhi, which was later published by Vitasta Publishers, Delhi, and is now a bestseller, critically acclaimed.

Gandhi was an ordinary man not without his fears, whims, apprehensions, a boy who was afraid of ghosts, robbers, multiplication tables, who rose above these fears to emerge as a moral icon, gaining an extraordinary status to be revered all over the world.

You wrote another book on Martin Luther King as he was influenced by Gandhi. Can you tell us what led to this book?

This book also was the result of another remark of another of my MPhil students.

Before that, while I was researching for my PhD thesis on Robert Nozick at the American Centre, Delhi. I came across the autobiography of King (edited by Clayborne Carson), I was completely fascinated by his life story and read all the books that I possibly could at the Centre — ignoring Nozick in the bargain. At that point of time, I thought maybe I’ll do my post-doctoral research on Martin Luther King, Jr. some day.

Later it was during another of my Conflict Studies’ lecture that one of my students (not a belligerent one this time) asked me to write a book on King. So that got me thinking and the book happened. It is a year since the book has been published, once again, by Vitasta Publishers, Delhi, (it has one full chapter on his India Connection) and I am happy readers have good words to say about it.

You are a fabulous teacher. Do you think your books made an impact in the way you wanted? Or was it more what you said?

I don’t know if I am a fabulous teacher, but yes, I know I am a very passionate teacher.

Yes, I think so. Let me cite an example. The MPhil student who had nudged me into writing a poetic biography of Mahatma Gandhi, and who was a great critic of Gandhi, on my insistence, read many books on Gandhi and right now, this critic of Gandhi has become a supporter of Gandhi and has become a lecturer in Political Science, specialising in Gandhian studies.

I was delighted when readers wrote saying that my book impacted them in a positive manner and since it was a poetic biography, they kept going back to it. In fact, Ballad of Bapu received more love than I had anticipated, so much so that I have given a number of talks on the book and conducted many workshops in many educational institutions followed by very fruitful and intellectually stimulating discussions.

Do you think Gandhi is pertinent in the current world? Why?

Gandhi can never be irrelevant in the world. Gandhi and Gandhism are for all times. He stood for truth and non-violence and truth and non-violence can never be irrelevant. Martin Luther King Jr. had followed his principles, time and again reiterating, that it was Gandhi who had inspired them during the Montgomery Bus Boycott and even later.

Gandhi was an ordinary man not without his fears, whims, idiosyncrasies and apprehensions, a boy who was afraid of ghosts, robbers, multiplication tables, and who rose above these fears to emerge as a moral icon, gaining an extraordinary status to be revered all over the world.

His values of Truth and Non-violence can never lose their relevance in this topsy-turvy, highly materialistic, self-centred and consumerist world. How can we ignore his supreme humanism, his overpowering love for everyone — even his enemies?

The Dalai Lama very rightly says, “He implemented the very noble philosophy of ahimsa in modern politics and he succeeded. This is a very great thing.” While the other ancient philosophers merely preached the philosophical aspects of Truth and Non-violence, his very life was a series of experiments with truth. He was a man forever evolving, trying to better himself in every way. Beleaguered humanity desperately needs to rededicate itself to the eternal values of nonviolence, truth, world peace and altruism otherwise, things will continue to be bleak.

What values of Gandhi do you think are the ones that are most relevant?

Truth, non-violence, love and compassion are values that will always be needed in this bleak world. An eye for an eye, will make the whole world blind, as he so powerfully believed. Why crave for this blindness and hurtle down an abyss?

Such peace revolutionaries like Nelson Mandela, Dalai Lama, Desmond Tutu, and Martin Luther King Jr. wouldn’t have been inspired by Gandhi had his values not been so precious. “If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, thought, and acted, inspired by the vision of humanity evolving toward a world of peace and harmony. We may ignore him at our own risk,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr had so eloquently said, reiterating time and again that Gandhi taught him his operational technique of fighting for civil rights.

Barack Obama, who holds Gandhi in great esteem had said:“I have always looked to Mahatma Gandhi as an inspiration because he embodies the kind of transformational change that can be made when ordinary people come together to do extraordinary things.”

The co- founder of Apple, Steve Jobs, maintained that Gandhi “showed us the way out of the destructive side of the human nature. Gandhi demonstrated that we can force change and justice through moral acts of aggression, instead of physical acts of aggression. Never has our species needed this wisdom more.”

So, we need the Gandhian wisdom and perception of love, truth, peace, moral acts of aggression and forgiveness, otherwise there is nothing but a grave new dystopian world staring at us.

Has reading and writing on Gandhi impacted your life?

Yes, it definitely has. In fact, the first Gandhian that I came across was my father. My grandmother was aghast when one day the sweeper had not come, he picked up the broom and cleaned all the toilets in the house. And another day he made him have tea and breakfast with us. My granny was once again indignant, but later many interactions later, she also started subscribing to his point of view and was almost embarrassed of her earlier behaviour and developed a deep love for the underprivileged.

My father’s library was a bibliophilic treasure and I read all the books on Gandhi, later I got books from the school library too. As a collegian, I read many books on Gandhi and they had a great impact on me.

Let me cite an incident from my career. It was my first year as a college lecturer in a post-graduate government college for boys, which was known for its notorious elements. Straight from the university, I was brimming with idealism and Gandhian ideals and fired with an ardent desire to change the world (still am!). During an invigilation, I found a hulk of a boy brazenly cheating, while the senior co-invigilator looked the other way. I dashed towards him and was appalled to find a big knife stuck to his desk. I quickly pulled out the chits from under his answer sheets and raced towards the Principal’s office, his threats following me with a full- throated stridence. Tumko dekh loonga. Mera Career barbaad ker diya [I will teach you a lesson, you spoilt my career].

Later, that evening, I met him at the railway station. He was going to Mathura and I, to Delhi for the weekend. He didn’t recognise me, but I did. I walked up to him and said, you had said, that you would see me – “See me, I am right here. Do you want to beat me up? Come do it?” Dumfounded, he looked at the chit of a girl standing before him, and when he realized who I was, he fell at my feet, apologizing profusely. He now says, that was the turning point in his life.

At the risk of sounding pompous, let me say, that it has become my second nature not to nurse grudges, and I try to spread as much love around me, as possible. Yes, Gandhi and Gandhism have impacted me in a big way.

Do you think Gandhi can impact the younger generation?

Gandhi can definitely impact the younger generation if he is presented to them in a very interesting manner, through role-playing, skits, workshops etc. His values of truth and non-violence transcend all geographical boundaries and time. Bapu had fought for human rights in South Africa, achieving unprecedented success. He was indeed “a powerful current of fresh air –like a beam of light” as Nehru described him. We need this beam of light, this powerful current of fresh air as never before.

We should not forget that he was an ordinary man who rose above his ordinariness by sheer moral force, even calling off the Non-Cooperation Movement at the height of its popularity, because the violence that was unleashed at Chauri Chaura, on 4 February 1922 (a village in Gorakhpur District of Uttar Pradesh), was not in conformity with his ideology of non-violence, and he did penance for what he saw as his culpability in the bloodshed. Only a man with great moral fibre could have taken such a decision, fully aware of the criticism that would follow in its wake. Such incidents as these, need to be presented to the youngsters in a proper manner, so that their minds are cleaned of prejudices and misconceptions.

For Gandhi, cleanliness was very important, and who can deny the importance of cleanliness? There was a time when the iconic film Lagey Raho Munna Bhai had created a revolution in young mindsets, I myself being a witness to many such heart-warming scenes. When a parent who had come to drop his daughter to college, aimed tobacco spittle in the college premises, a boy picked up the broom lying nearby and swept it away, to the intense chagrin of the daughter, and the father, realizing his mistake, apologized profusely.

But things are changing fast, so are young mindsets, a sort of skepticism is setting in, so we need to present Gandhi to the younger generation with a conviction which is more robust than before.

Should we be propagating his ideals? If so, what would be the most effective way of doing so?

Of course, Gandhi’s ideals need to be propagated especially in these dark, despairing ages when the forces of fascism are wreaking havoc throughout the world. “Be the change you want to see around you,” Bapu had said, so we should try to be that change, wherever we feel the need for change. Preachy pedagogy can only boomerang, so we should make his principles a way of life, so that the youngsters learn from them. We need to change ourselves first, if we want to spread his principles.

Gandhi had said, “Power is of two kinds. One is obtained by the fear of punishment and the other by acts of love. Power based on love is a thousand times more effective and permanent than the one derived from fear of punishment.” (Young India, January 8, 1925).

To many naysayers, this might smack of naiveté, but no one can deny the fact that love and positivity are the weapons in our hands, which should be amply used to positivize the negative forces around.

As an academic, should Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments with Truth, be introduced as part of the school curriculum in India? Do you think that would have a good impact on young minds?

From my experience as an academic, I can say this very confidently that students prefer to crinkle their noses at course books. My Experiments with Truth as part of the syllabus is indeed a great idea as a symbolic gesture venerating the great soul, but what I sincerely feel is that it is the need of the hour to devise such courses where My Experiments with Truth is part of supplementary reading. I believe, students should read it out of curiosity and not out of compulsion. Understanding the essence of Gandhian philosophy should not be forced on young minds. Yes, short-term courses and interestingly designed workshops can go a long way in inculcating the Gandhian spirit in youngsters.

Let me make myself clearer. Some years back, I was very happy to see youngsters at the Delhi Book Fair flocking to buy My Experiments with Truth. When asked the reason, they told me they were buying the book because in their first year of under-graduation, it was prescribed as a reference book for a course they were undergoing which, was meant for students of all disciplines. It is heartening to know that My Experiments with Truth continues to be a bestseller. Both the supporters and the detractors, own copies of it.

What do you see as the future of Gandhism in India?

With Gandhi’s assassins being glorified with impunity, and his ideals given lip service to, only during particular days, Gandhism’s future looks bleak. But it is the responsibility of all the right-thinking individuals to pick up cudgels on behalf of this moral icon and disentangle him from the clutches of the naysayers and detractors.

At a time when Gandhi’s killers are being venerated, Gandhi and what he stood for, needs to be revived. Martin Luther King Jr. had been influenced in his crusade for civil rights and non- violence by Bapu; he visited India in 1959, calling his visit a pilgrimage. During his visit he remarked that the spirit of Gandhi was very much alive in India, but alas, we are slowly forgetting the saint in beggar’s garb.

Youngsters have no qualms about heaping venom at Gandhi, forwarding fake WhatsApp messages denigrating him. As I mentioned earlier and I repeat: we should not forget that he was an ordinary man who rose above his ordinariness by sheer moral force, as illustrated in his calling off the Non-Cooperation Movement at the height of its popularity, because the violence that was unleashed at Chauri Chaura, on 4 February 1922. This did exhibit his immense moral fibre.

Who can deny the importance of truth, forgiveness and non-violence in this age of crass materialism and consumerism! Gandhi had said, “Be the change you want to see in the world”, so we have to bring about the revolution within ourselves and change the world for the better, otherwise the world is doomed. In this context, allow me to quote Martin Luther King Jr, “Over the bleached bones and jumbled residue of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words, ‘Too Late’”. Why should we wait for it to be ‘Too Late’?

As a teacher I have had the opportunity of interacting both with the millennials and the Generation Z and notice a world of difference between their mindsets.

I know of many youngsters who are running organizations, the mission of which is to create a more equitable and inclusive society.

I had a very fruitful discussion with a young NRI nephew who was in India six months back and the essence of what he said boiled down to this, “The world is fighting the evils of discrimination, race, gender, and we cannot forget that Gandhi was a pioneering force in this direction. More and more people should come forward to run programmes which are consistent with his constructive programmes.” He heads one such programme which is very popular.

Then there are some from the hypercognitive Generation z who vociferously argue, “How can the oppressors rid themselves of the guilt of what the guilty have perpetrated in the past — how can they justify their oppression? We need to be proactive — and need to follow Malcom X and Not King or Gandhi. No more candlelight marches, no more offering of roses to our oppressors! We need to hurl stone for stone. You got your jobs in golden platters, our generation has no jobs, no economic security, no health security, we are surrounded by environmental hazards of all sorts, and we need to do something.”

Well, we cannot save ourselves from the guilt of the devastation that we have wrecked on the young generation but in these crosscurrents of hatred and enmity, it is humanity which is suffering, and needs to be resurrected. No matter what rampant negativities we are surrounded by, I staunchly believe, that the tenets of Gandhism will have to rise from their ashes and come to the rescue of a doddering, staggering humanity. Otherwise we are doomed.

Thanks a ton for this great opportunity, Borderless journal and Mitali Chakravarty. It was an honor answering these questions.

Thank you for giving us your valuable time, Santosh Bakaya.

This online interview was conducted by Mitali Chakravarty.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are solely that of the interviewee.