Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

Title: Selected Essays: Kazi Nazrul Islam

Author: Kazi Nazrul Islam

Translator: Radha Chakravarty

Publisher: Penguin Random House

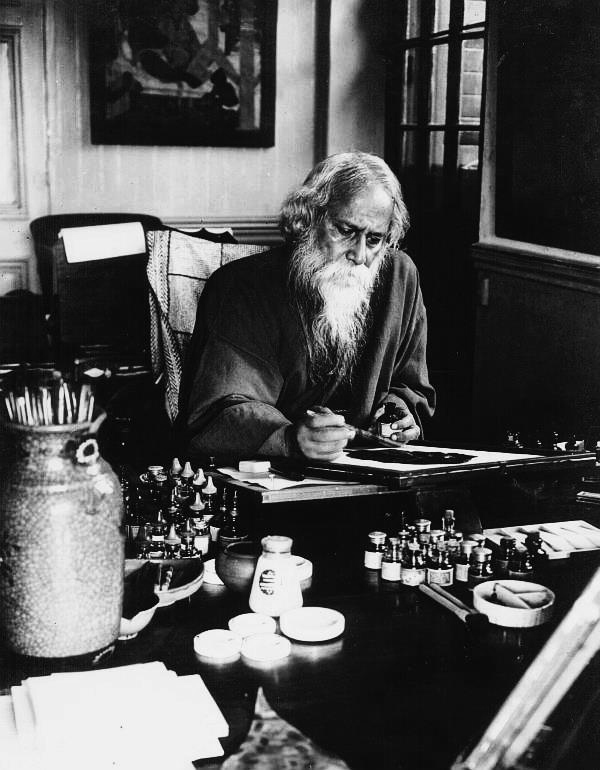

The Bengali poet, Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976), is widely remembered as the fiery iconoclast who fought against the structures of oppression and orthodoxy. The iconic bidrohi or ‘rebel poet’ of Bengal, Nazrul continues to be loved for his songs and poetry that were aimed at arousing the rebellious spirit of both Hindus and Muslims alike. But what of his prose, his journalism, and his politics? Selected Essays reveals to us the extraordinary versatility of Nazrul as a writer, thinker, and activist. Addressing subjects as diverse as social reform, politics, communal harmony, environmental concerns, education, aesthetics, ethics, and philosophy, this rich collection showcases Nazrul’s dynamic vision and unique use of language as an instrument of change. The essays chart his evolving consciousness as a thinker, writer, and activist, offering vivid glimpses of the ethos of his times, his relationships with leading figures such as Tagore and Gandhi, and his active engagement with social, political, and cultural processes.

Of the forty-one essays selected here, (three undated), the first thirteen are all written in different places all in the year 1920. That was the year Nazrul returned to Bengal after serving in Karachi during World War I as a member of the Bengal regiment of the colonial British army. Reacting to the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre he writes, “May the Dyer monument never allow us to forget Dyer’s memory” because on that occasion Hindus and Muslims embraced each other and wept together as brothers. They shared the same agony as children of the same womb. In ‘Strike’, he praises the social awareness that has swept among the ranks of the labouring class and believes that the “protest is not just a rebellion, but the death-bite of the suffering, moribund class”. When some migrants were fired upon after a clash with the armed police at a place called Kanchagarhi, he asked in ‘Who is Responsible for the Killing of Migrants?’, whether anyone can ever tolerate such injustice towards humanity, conscience, self-respect and independence and states that they are no longer going to passively accept such assaults. ‘Awakening Our Neglected Power’ contends that democracy or people’s power cannot be established in our country because of the oppression inflicted by the Bhadra[1] community.

There are several essays in which Nazrul speaks about the state of National Education, he envisages ‘A National University’, and in a very powerful piece that he wrote from Presidency Jail in Kolkata on 7 January 1923, titled ‘Deposition of a Political Prisoner’ he reveals his self-confidence:

“If anything has struck me as unjust, I have described it as injustice, described oppression as oppression, named falsehoods as falsehood. …For that endless mockery, insults, humiliation and assaults have been rained on me, from within my home and beyond. But nothing whatsoever has intimidated me into dishonouring my own truth or my own Lord. No temptation has overpowered me enough to compromise my integrity or to diminish the immense self-satisfaction gleaned through my own endeavours…. I repeat, I have no fear, no sorrow. I am the child of the elixir of immortality.”

Nazrul grew up in a traditional religious environment, yet in his writings he drew upon both Hindu and Islamic sources, and expressed a faith that transcended the limits of any single religion. In several essays, he harps on the problems of Hindu-Muslim amity and enmity and warns us about “this hideous business of purity of touch and untouchability”. He wants only humans to live in India as brothers and wants everyone to be wary of the terrible deceptions created by both the religions.

In the essay ‘Temple and Mosque‘, he states that both parties have the same leader, and his real name is Shaitan, the Devil. Written in response to the communal riots that broke out in Kolkata on 2 April 1926, he feels that those very same places of worship that ought to have been bridges between heaven and earth are instead causing harm to humanity today, and so those temples and mosques should be broken down. In another essay titled ‘Hindu-Muslim’, penned the same year, Nazrul talks about the question of an internal tail in human beings. He says, “There’s no telling what animal excitement lured the human mind to discover a substitute for tails in the beard or tiki[2]!” He further elaborates:

“Both Hindu and Muslim ways of life can be tolerated, but their faith in tikitwa and daritwa, the orthodox ways of tiki and beard, is not to be borne, for both instigate violence and killing. Tikitwa is not Hindutwa, it is perhaps punditwa, the way of the pundit! Likewise, the beard, too, is not Islamic, it is mullatwa, the way of the mullah. These two types of hair tufts, marked with religious dogma, are precisely the reason for all the conflict and hair-splitting we witness today!”

Though it is not possible to discuss all the different editorials, book reviews, and political pieces that are included in this collection, one must mention at least two essays that speak about literary issues as well. In 1932, Nazrul wrote for Patrika (subsequently reprinted in Bulbul the following year), an interesting piece titled ‘World Literature Today’. In it he states that there are two kinds of writers present in the world today and their different tendencies have assumed immense proportions.

“Ranged on both sides are great war heroes, champion charioteers of the battlefield. On one side are the dreamers, such as Noguchi, Yeats and Rabindranath, and on the other, Gorky, Johan Bojer, Bernard Shaw, Benavente and their ilk.”

But Nazrul’s ire in being ostracized comes out clearly in ‘A Great Man’s Love Is a Sandbank’ (1927), where he criticises the high-handedness of Rabindranath Tagore. He begins by telling us how he was a prisoner of state at the Alipore Central Jail when he was informed by the assistant jailor that Tagore had recognised Nazrul’s talent and dedicated his play Basanta to him. The other political prisoners present there had laughed at him not in joy but in incredulity. For him, the blessing turned into a curse. His very close friends and state prisoners also turned away from him. He realised what massive internal damage this outward gain had caused him. Busy with his political agenda, he didn’t have the time to sit and meditate as advised several times by Tagore. So Nazrul writes, “I find that the brighter my countenance shines in this glory, the darker some other famous poets’ faces seem to appear.” He mentions that he had grown accustomed to police torture but when literary personages begin to torment one, their brutality knows no bounds. “Alas, O youthful new literature!” His crime was that young people celebrated his work. He laments further,

“That Kabiguru[3], revered by both parties like the grandsire Bhisma, should assent to this plot of killing Abhimanyu, is the greatest sorrow of our times. …As for me, I have discarded that topi–pyjama—sherwani–beard look[4], only out of fear of being mocked as a ‘Mia Saheb’. But still there is no respite for me…. Now we get the feeling that the Rabindranath of today is not the same Rabindranath we have always known.”

That the trajectories and beliefs of Tagore and Nazrul went in the opposite direction is well- known. In the essay, Nazrul then further continues his complaints against Tagore. He questions whether they have been considered as his enemies, simply because they didn’t go to him frequently. Also, since the goddess of wealth blessed him, Kabiguru did not know what dire poverty the new writers had to struggle against, languishing in conditions of starvation or semi-starvation. So, he humbly requests Kabiguru not to sprinkle salt on their wounds by mocking the impoverishment that is their singular affliction, for that is one form of heartlessness that they cannot tolerate.

Of the last three essays written in 1960, namely, ‘The Science of Life’(where men “are surrounded by all sorts of travails and sufferings, and many of them cannot be alleviated”), ‘A Point to Ponder’(where the nation faces an immense problem regarding the dispute about the instructions and procedure for the worship of the mother, the Bharatmata, our Mother India) and in ‘What We Need Today’, Nazrul speaks of the necessity of a “vast tumult in India”. Making his readers aware of the vast duplicity and trickery in the name of religion, he warns that unless one avoids the baseness of being subjugated by an external power, there is no prospect of heaven for us, only the grotesqueness of hell. He wants the kalboishakhi, the wild summer storm, to “approach in all its fury, rearing his head like a hooded serpent swimming in the unchecked torrents of an ocean of blood” and sweep everything away.

Before concluding one should also make a few comments on the translation. As a veteran translator, Radha Chakravarty, has successfully managed to transcreate some very difficult Bengali idioms, cultural nuances and analogies that Nazrul used in some of his essays. As she admitted in the Introduction, “[T]ranslating Nazrul’s prose proved to be a challenge, as demanding as it was exhilarating. …The endeavour demanded experiment and creativity rather than mechanical lexical ability and involved some difficult choices…Literal translation has been avoided, with greater focus on the sense, emotion, intellectual import, rhetorical features and stylistic particularities of the Bengali source texts.” She further adds that the present translations stemmed from a desire to bring Nazrul’s essays to a contemporary audience in South Asia and the rest of the world, to draw attention to his literary achievement as well as his significance as a writer, thinker, activist, and visionary. Though a lot of research and translation projects on Nazrul has been going on in Bangladesh for quite some time (where he holds the status of National Poet), in India, especially in West Bengal, the response is still rather lukewarm. Hence this volume is strongly recommended as a collector’s item.

[1] Literally decent but here indicates the bourgeoisie.

[2] A tuft of hair at the back of a tonsured head

[3] Tagore

[4] Cap-pyajama-longcoat – these with a beard were associated with the genteel muslim look – the look of the Mia Saheb

CLICK HERE TO READ THE EXCERPT

Somdatta Mandal, critic and translator, is a former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International