Author Keri Hulme (1947-2021) was the first New Zealander to win the prestigious Booker prize for the bone people*. Keith Lyons recalls times he spent in a remote coastal settlement with the humble writer, who remains a divisive enigma.

“You want to know about anybody? See what books they read, and how they’ve been read…” Keri Hulme

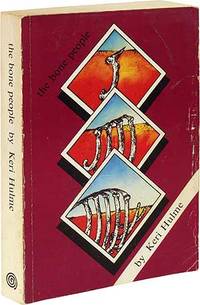

I was in high school when I heard the news that Keri Hulme’s the bone people had won the 1985 Booker Prize, literature’s most prestigious award for a novel in English. At 38 years old, she was the first New Zealander to receive the prize. Hulme became the first author to win with their debut novel. Later, in 2013, Eleanor Catton became the second Kiwi, the youngest winner of the Man Booker Prize, and also holds the record for the longest novel, 832 pages.

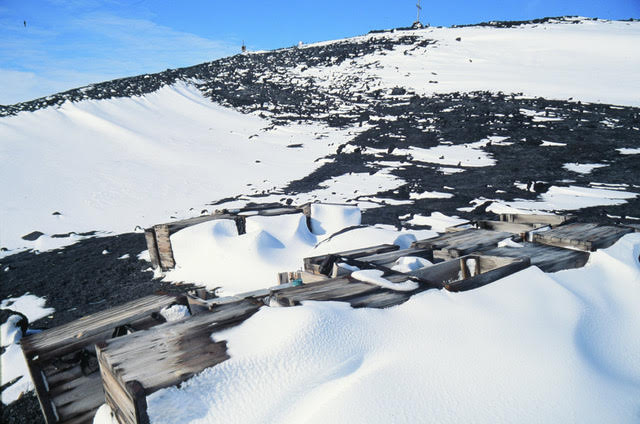

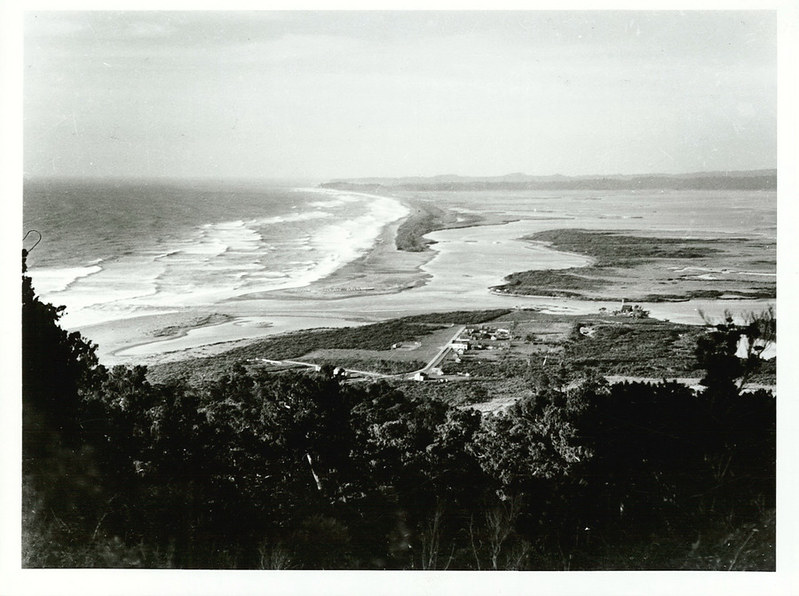

The following summer while hitchhiking around the South Island, I visited the small settlement of Okarito on the West Coast, where Keri had built her own house and lived since the 1970s. A converted schoolhouse in the former 1860s gold mining town was the main accommodation available: a youth hostel with bunk beds. I’d been attracted to the area because of the rugged coastline, placid tidal lagoon, mountain views and the elegant white herons which nested in the nearby forest.

Even though I’d struggled through an early edition of the bone people, I wasn’t as enthralled about the book as some of my fellow travellers who occupied bunk beds in the spartan hostel. Several European visitors carried copies of the book, which had been translated into many languages, several with different covers. It seemed that every day I went out walking along the main street of the settlement (population: 13 permanent residents), there would be an earnest woman from Cologne clutching Unter dem Tagmond or a young couple from Aarhus plodding along the road in the hope of finding Keri’s octagonal tower two-story house. Visitors wandered over the sand dunes desiring to encounter the acclaimed pipe-smoking author, beach combing for driftwood or gemstones washed up on the high tide.

There for the scenery and sanctuary of the coast, lagoon and native forest, rather than to spot the world-famous author, I did locate her house further along the settlement’s main road. A sign on the gate read “Unknown cats and dogs will be shot on sight”. The hostel warden Bill Minehan, who lived next door to Keri, told me she didn’t really like the attention or surprise visitors. Some of the other residents, protective of the community’s drawcard, would give wrong directions, so visitors after sightings of the elusive author could be seen pacing up and down the rutted grass airstrip — signposted Okarito International Airport and flying the Okarito Free Republic flag — or sidestepping around sheep grazing on the settlement’s rough golf course.

Often, after rains, Keri’s front yard flooded, creating a moat to protect her from rubberneckers. The Okarito Free Republic flag sometimes fluttered from a flagpole at Keri’s house, along with an alternative New Zealand flag, with a stylised spiral fern frond, made by Austrian painter and artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser. She moved to Okarito after winning a ballot for a section of land in 1973, building the house herself, lining bookcases with some 6,000 books, and setting up her writing desk with views out to the sea.

Keri was increasingly portrayed as reclusive. Rumours were that she’d spent all her Booker Prize thousands on alcohol from the Whataroa Hotel, some 25 km away. She didn’t like meeting strangers. She was reluctant to give interviews, and very rarely did she allow anyone into her house. She preferred solitude. “A large part of my life is the surge of the sea, listen to the sea, the pulse of the sea,” she once said.

I did catch a glimpse of Keri on my last day when returning a key to Bill — she was wielding a hammer, fixing the side of her house. The sweet aromatic scent of pipe tobacco floated in the humid air. Then I realised it was probably her I’d seen surf-cast fishing while on a long coastal walk towards the lagoon’s outlet into the Tasman Sea.

Bill let slip that Keri was formidable, but not unbeatable, at Scrabble. Having told him I had been at a Catholic boys’ school in Christchurch, and that I was also a writer, he asked if I knew any good high-scoring Scrabble words. I gave him ‘exorcise’ and ‘queazy’.

One of Keri’s favourite Scrabble words, I later found out, was ‘syzygy’, meaning the alignment of three celestial bodies. Three main characters make up ‘the bone people’. Keri said the characters for her book first came into her imagination when she was eighteen years old. After dreaming about a mute child with strange green eyes, she mused over the vision, eventually developing it into the character of the shipwrecked boy Simon Peter, whose life is intertwined with what one critic described as ‘his child-battering stepfather and a virgin feminist’.

The eldest daughter of a carpenter, whose parents came from Lancashire, and a mother who came from Orkney Scots and Māoris, she grew up in my hometown Christchurch. Her father died when she was aged eleven. After leaving school she dropped out of university part way through a law degree. She worked as a tobacco picker, in a woollen mill, delivering mail, cooking fish and chips at a takeaway shop, as a pharmacist’s assistant, a proofreader at a local newspaper, and in television production.

It took her almost two decades to finish the novel. She spent a dozen years trying to find a publisher. All New Zealand’s main publishing houses rejected the manuscript outright or insisted on extensive heavy re-writing before they would consider taking on the book.

In the end, it was published by a small obscure three-woman feminist collective (it was only the second book they produced), and typeset by students at a university newspaper, with an initial print run of just 2,000 copies. The book, which contained numerous typographical errors, was launched at an event at a teacher’s training college.

The year after its humble beginnings, the bone people won the Oscars of world literature, against the odds and against such literary heavyweights as Peter Carey, Doris Lessing and Iris Murdoch. The somewhat controversial win showcased writing from New Zealand to an international audience, who would perhaps only be aware of the likes of modernist short story writer Katherine Mansfield or Janet Frame, who explored madness and language.

Hulme’s contribution, blending indigenous myth and Celtic symbology, and set in a distinctly wild coastal New Zealand setting, is described as “an unusual story of love”’ or in the Amazon blurb “a true evocation of loneliness and attempts by deeply flawed people to connect to each other”. The main character of three, part-Māori artist Kerewin is convinced that her solitary life is the only way to face the world. How autobiographical is it, you ask? The more you delve into it, the more you find similarities with the unusual literary star, who increasingly got dubbed “reclusive” by the media because she wished to remain out of the limelight.

Part of the legend around Hulme is about the surprising success of her debut novel. She didn’t fancy her chances of winning the Booker Prize, so was in the US when the awards ceremony was held in London (plumes of cigarette smoke swirled up in the film footage) — she was the only contender not in the audience at London’s Guildhall. When she was called in her Salt Lake City hotel room during the event, she didn’t believe the news down the phone line. “You’re pulling my leg, aren’t you?” she said, “Oh, bloody hell.”

She was full of self-doubt. The literary world had a mixed response to her breakout novel. “Set on the harsh South Island beaches of New Zealand, bound in Māori myth and entwined with Christian symbols, Miss Hulme’s provocative novel summons power with words, as a conjurer’s spell,” wrote one New York Times review. “She casts her magic on three fiercely unique characters, but reminds us that we, like them, are ‘nothing more than people’, and that, in a sense, we are all cannibals, compelled to consume the gift of love with demands for perfection’.

Another review in the same publication was more critical. “It’s not so much that the novel offers ‘a taste passing strange’ as the author notes in the preface — interior monologues, disjointed narratives and vulgar language, after all, are hardly news these days. It’s more that the novel is unevenly written, often portentous, and considerably overlong.” The Guardian described the bone people as “a morass of bad, barely comprehensible prose.”

Even one of the Booker Prize judges, Joanna Lumley, was against it being picked as the winner, saying its subject matter was ‘indefensible’. A recent article described the bone people as one of the most divisive novels in Booker Prize history. The four words to sum up the book were violent, disturbing, poetic and striking.

While dismissed by some as unreadable and pretentious, in New Zealand the novel combining reality with dreams was seen as a masterpiece by others with its vision of a society regenerated by the adoption of Māori values and spirituality. For some, it challenged their worldview and sense of place at home in the world. Author Joy Cowley wrote, “Keri Hulme sat in our skulls while she wrote this work . . . she has given us — us.”

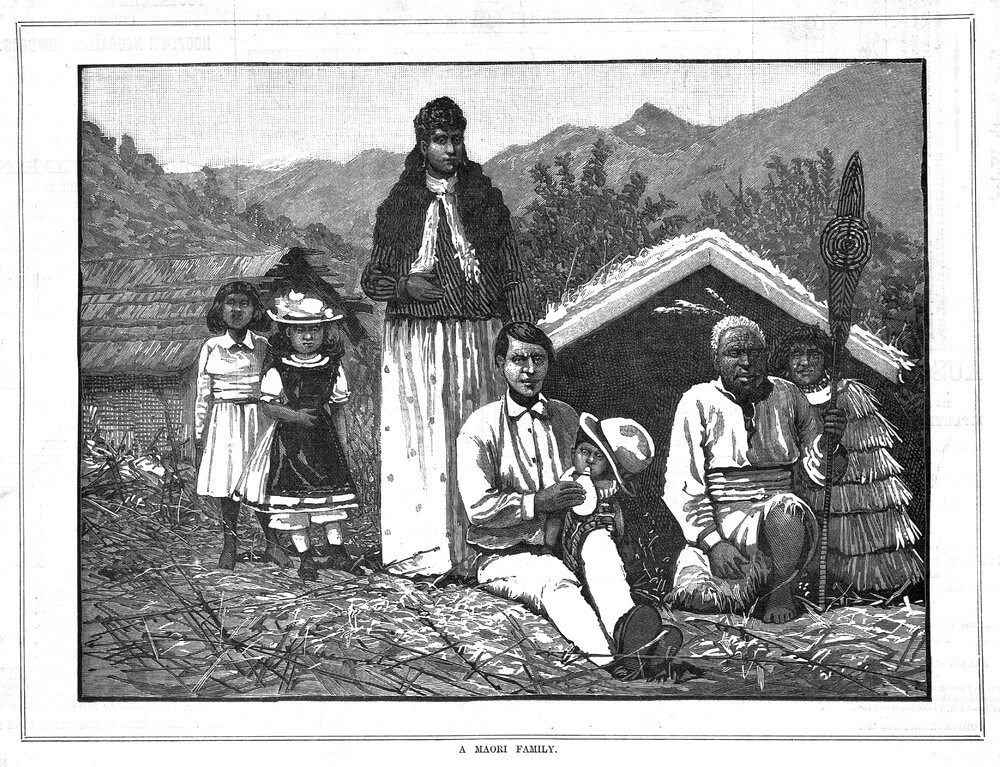

Keri said she wanted the novel to harmonise New Zealand’s two major cultural influences, indigenous Māori and European-descendent settlers (she herself shared both heritages). If you were to discover other authors who have explored in new ways what it means to be Māori, look up works by Patricia Grace and Witi Ihimaera, or for a raw look at the debilitating effect urban life has had on Maori, Alan Duff’s Once Were Warriors.

By the time I returned to Okarito the following August holidays to write a story for the Youth Hostel Association, the secluded hamlet had grown in population with the addition of a few more hardy souls and holiday houses, I only saw Keri a few times. One time, after gutting some snapper, she was off to clear the mailbox and collect the newspaper at the highway junction (there was no shop in the township). Another time she was cleaning a gun, bespectacled, and wearing her trademark red bush shirt. Like Hemingway, Keri liked hunting, (she favoured a .22 Ruger rifle among her collection of guns, swords and knives), and often took to the forest in search of deer.

Another time she was assembling poles, screens, nets, waders and buckets for the official start of the white baiting season. My father had worked in marine administration for decades, which included the monitoring of whitebait jetties and official seasons, so I knew a few things about the obsession. “Are the whitebait running yet?” I asked as she made the finishing touches to repairing nets. “Any day now,” she replied, looking expectedly towards the clouds billowing in the west. The season officially started the following day, and she had already checked her favoured locations for a 5am start. Normally a night owl and late riser, even her writing routine was swept aside for the ten weeks of the season when she was out trying to catch the coveted tiny fish. While throughout the year she might be catching rig or kahawai in the surf, netting for flounders in the lagoon, or trying to land salmon or trout in the rivers, her main springtime preoccupation was catching whitebait, the prized juveniles of migratory Southern Hemisphere fish.

I helped Bill load up driftwood onto the back of his vehicle before the rains set in, for use as firewood at the hostel (with a load for Keri too) and found some fool’s gold in quartz rock. Bill confirmed my folly. I gave him some more Scrabble words: Quartzy and Quickly.

That next summer I returned again to ‘The Big O’, hitching on the dusty corrugated gravel road to the coast with its pounding surf, driftwood sculptures and star-filled nights. Just before Christmas, with Bill away, Keri asked me if I could look after things at the hostel and check her place while she visited relatives on the other side of the South Island. The only other person staying medium-term was a German dwarf actor, who joked with me that he was a big man in European television and movies. Before she left, she dropped off a carton of a dozen beer, and some frozen whitebait, silvery eyes glistening through the plastic bag, with advice on how to make a batter for fritters with beer, flour, salt, and fresh parsley growing outside the hostel. “You could spice it up with some chilli pepper,” she said, pointing to a half-full jar of pepper left behind in the communal pantry by a Chilean backpacker.

Later, as we drank beer and watched the sunset from the old wharf, I mentioned to Manfred that even though Keri showed typical West Coast conviviality, we never once talked about writing. We’d talked about the moods of the weather, birdcalls from creatures seldom seen, what remedies protected vegetable gardens from slugs, and strange things which washed up on remote beaches. Having lived in that place for so long, she had plenty of stories about incidents, characters, or her own eccentric foibles. And I think that seeing her as a three-dimensional person (almost ignoring that she was a Booker Prize winner) rather than a 2-D writer made a difference, because it took away the pretensions and the expectations. She was direct, and also had a dry sense of humour. Manfred liked her rugged independent spirit, and kindly nature, not just because she had given us a box of beer. “She is like a good Kiwi bloke, yah?”

However, in the literary world, there was an expectation that a second novel was due. Her debut novel was on track to sell over a million copies. She’d retained the film rights, as its form couldn’t be easily adapted to the big screen. She believed that some stories work best ‘behind human eyes, not in front of them’. Surely she wasn’t going to be a ‘one-hit wonder’ like the band who sang the Macarena, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird or The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger?

She finally announced her second novel, about fishing and death, she finally announced. And it would be called BAIT. She published a second collection of poems in 1992, and two collections of short stories appeared in 1986 and 2005. As for BAIT, it later would be published along with its twinned novel, On the Shadow Side.

She once declared she didn’t believe in writer’s block. “I know about distractions, laziness, daydreaming, stressful events that push writing to the background, and the sheer enjoyment of doing other things for a change … I am a slow, but very, very persistent writer.”

I can’t exactly recall when the last time it was I saw Keri. I just remember seeing her heading out on a fishing trip, along the windswept beach towards the lagoon and its ever-shifting outlet to the sea. She gave me a nod, and gradually faded into the misty greyness of the day and the distance. That night, after sunset at the beach, I witnessed the rare phenomena sometimes seen when the surf glows neon-blue from a bioluminescent algal bloom or plankton. Above it and beyond, the stars twinkled.

A decade ago, after almost forty years at Okarito, Keri left to move to the other coast, where she felt more at home. She had been dismayed by the development with ‘very ugly McMansions’ holiday homes visited by outsiders who would fly in by helicopter or plane. Her council rates were becoming unaffordable. She was also suffering from arthritis in her hips, back and elbows.

A few years ago, I went back to Okarito with a friend, but it felt different without her being there. We both hold the wish to buy her house, mainly in memory and tribute to Keri’s life and work, and also, to inspire our own writing. Though we both admit that Keri has fished all the best words, and woven the most compelling tales.

The much-anticipated second novel was never published, nor was the promised third. She died in late December last year. A family representative said she wasn’t after fame or fortune. “There were stories of her being this literary giant. It wasn’t really something that she discussed. It was never about fame for her, she’s always been a storyteller. It was never about the glitz and glam, she just had stories to share.”

*Please note ‘the bone people’ all lower case is the correct version of her title

Keith Lyons (keithlyons.net) is an award-winning writer who gave up learning to play bagpipes in a Scottish pipe band to focus on early morning slow-lane swimming, the perfect cup of masala chai tea, and after-dark tabs of dark chocolate. Find him@KeithLyonsNZ or blogging at Wandering in the World (http://wanderingintheworld.com).

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL