‘I will cling fast to hope.‘

— Suzanne Kamata, ‘Educating for Peace in Rwanda’

Hope is the mantra for all human existence. We hope for a better future, for love, for peace, for good weather, for abundance. When that abundance is an abundance of harsh weather or violence wrought by wars, we hope for calm and peace.

This is the season for cyclones — Dana, Trami, Yixing, Hurricanes Milton and Helene — to name a few that left their imprint with the destruction of both property and human lives as did the floods in Spain while wars continue to annihilate more lives and constructs. That we need peace to work out how to adapt to climate change is an issue that warmongers seem to have overlooked. We have to figure out how we can work around losing landmasses and lives to intermittent floods caused by tidal waves, landslides like the one in Wayanad and rising temperatures due to the loss of ice cover. The loss of the white cover of ice leads to more absorption of heat as the melting water is deeper in colour. Such phenomena could affect the availability of potable water and food, impacted by the changes in flora and fauna as a result of altered temperatures and weather patterns. An influx of climate refugees too is likely in places that continue habitable. Do we need to find ways of accommodating these people? Do we need to redefine our constructs to face the crises?

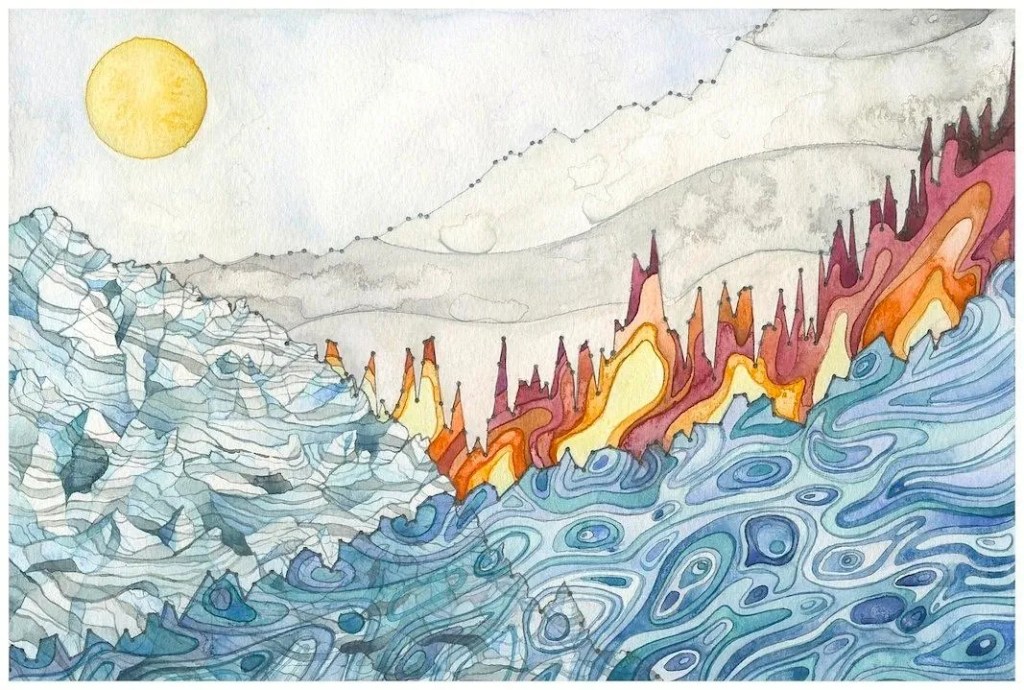

Echoing concerns for action to adapt to climate change and hoping for peace, our current issue shimmers with vibrancy of shades while weaving in personal narratives of life, living and the process of changing to adapt.

An essay on Bhaskar Parichha’s recent book on climate change highlights the action that is needed in the area where Dana made landfall recently. In terms of preparedness things have improved, as Bijoy K Mishra contends in his essay. But more action is needed. Denying climate change or thinking of going back to pre-climate change era is not an option for humanity anymore. While politics often ignores the need to acknowledge this crises and divides destroying with wars, riots and angst, a narrative for peace is woven by some countries like Japan and Rwanda.

Suzanne Kamata recently visited Rwanda. She writes about how she found by educating people about the genocide of 1994, the locals have found a way to live in peace with people who they addressed as their enemies before… as have the future generations of Japan by remembering the atomic holocausts of 1945.

Writing about an event which wrought danger into the lives of common people in South Asia is Professor Fakrul Alam’s essay on the 1971 conflict between the countries that were carved out of the 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent. As if an antithesis to this narrative of divides that destroyed lives, Luke Rimmo Minkeng Lego muses about peace and calm in Shillong which leaves a lingering fragrance of heartfelt friendships. Farouk Gulsara muses on nostalgic friendships and twists of fate that compel one to face mortality. Abdullah Rayhan ponders about happiness and Shobha Sriram, with a pinch of humour, adapts to changes. Devraj Singh Kalsi writes satirically of current norms aiming for a change in outlook.

Humour is brought into poetry by Rhys Hughes who writes about a photograph of a sign that can be interpreted in ways more than one. Michael Burch travels down the path of nostalgia as Ryan Quinn Flanagan shares a poem inspired by Pablo Neruda’s bird poems. Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal writes heart wrenching verses about the harshness of winter for the homeless without shelter. We have more colours in poetry woven by Jahanara Tariq, Stuart MacFarlane, Saranyan BV, George Freek, G Javaid Rasool, Heath Brougher and more.

In translations, we have poetry from varied countries. Ihlwha Choi has self-translated his poem from Korean. Ivan Pozzoni has done the same from Italian. One of Tagore’s lesser-known verses, perhaps influenced by the findings of sensitivity in plants by his contemporary, Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858-1937) to who he dedicated the collection which homed this poem, Phool Photano (making flowers bloom), has been translated from Bengali. Professor Alam has translated Nazrul’s popular song, Tumi Shundor Tai Cheye Thaki (Because you are so beautiful, I keep gazing at you).

In reviews, Somdatta Mandal has discussed The Collected Short Stories of Kazi Nazrul Islam, translated by multiple translators from Bengali and edited by Syed Manzoorul Islam and Kaustav Chakraborty. Rakhi Dalal has written about The Long Strider in Jehangir’s Hindustan: In the Footsteps of the Englishman Who Walked From England to India in the Year 1613 by Dom Moraes and Sarayu Srivatsa, a book that looks and compares the past with the present. Bhaskar Parichha has written of a memoir which showcases not just the personal but gives a political and economic commentary on tumultuous events that shaped the history of Israel, Palestine, and the modern Middle East prior to the more than a year-old conflict. The book by the late Mohammad Tarbush (1948-2022) is called My Palestine: An Impossible Exile.

Stories travel around the world with Paul Mirabile’s narrative giving a flavour of bohemian Paris in 1974. Anna Moon’s fiction set in Philippines gives a darker perspective of life. Lakshmi Kannan’s narrative hovers around the 2008 bombing in Mumbai, an event that evoked much anger, violence and created hatred in hearts. In contrast, Naramsetti Umamaheswararao brings a sense of warmth into our lives with a story about a child and his love for a dog. Sreelekha Chatterjee weaves a tale of change, showcasing adapting to climate crisis from a penguin’s perspective.

Hoping to change mindsets with education, Mineke Schipper has a collection of essays called Widows: A Global History, which has been introduced along with a discussion with the author on how we can hope for a more equitable world. The other conversation by Ratnottama Sengupta with Veena Raman, wife of the late Vijay Raman, a police officer who authored, Did I Really Do All This: Memoirs of a Gentleman Cop Who Dared to be Different, showcases a life given to serving justice. Raman was an officer who caught dacoits like Paan Singh Tomar and the Indian legendary dacoit queen, Phoolan Devi. An excerpt from his memoir accompanies the conversation. The other book excerpt is from an extremely out of the box book, Rhys Hughes’ Growl at the Moon, a Weird Western.

Trying something new, being out of the box is what helped humans move out from caves, invent wheels and create civilisations. Hopefully, this is what will help us move into the next phase of human development where wars and weapons will become redundant, and we will be able to adapt to changing climes and move towards a kinder, more compassionate existence.

Thank you all for pitching in with your fabulous pieces. There are ones that have not been covered here. Do pause by our content’s page to see all our content. Huge thanks to the fantastic Borderless team and to Sohana Manzoor, for her art too.

Hope you enjoy our fare!

Mitali Chakravarty

Click here to access the content’s page for the November 2024 Issue

.

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.