By Paul Mirabile

The good folk of Black Rock, Montana, USA, were not overly enthusiastic that a small, travelling circus would be coming to their peaceful town to make a one-night performance. They had heard disturbing stories about this circus from people out of state who had seen it or pretended to have seen it. Rip Branco, the mayor of Black Rock, felt a bit reluctant about authorising the performance, but the owners’ arguments won him over, half-heartedly. Besides, the children of Black Rock had never had the pleasure of seeing a circus, nor their parents for that matter.

So, many posters of the coming circus were nailed or pasted on the outer walls of the townhall, the school and at the farmers’ and factory workers’ cooperatives.

Strange tales circulated throughout the region: the performers originated from the Old World speaking alien tongues. Hearsay spread that many of the performers were abnormal individuals, freaks of nature, they said; and that the whole show was a razzle-dazzle of shamelessness, cynicism. What if this hearsay was the truth! The majority of the folks of Black Rock were convinced of its veracity.

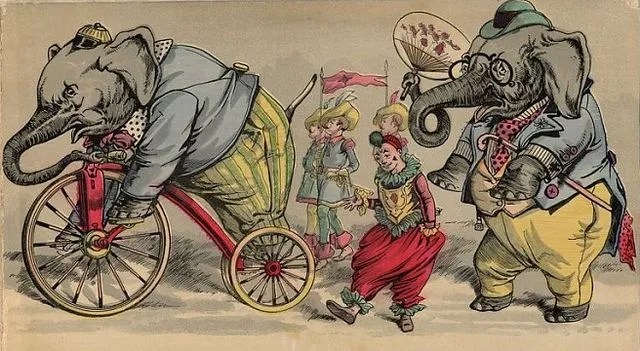

In spite of all this hullabaloo the circus rumbled into town. Through the narrow, main avenue of Black Rock, lined with shops, banks, the townhall, the police-station and the Wednesday open-air market, crawled ten or eleven caravans painted in colourful figures of clowns, mountebanks, lions and elephants, and odd looking creatures whose appearances the townspeople, gaped at wide-eyed. They watched this slow-moving spectacle as they stood on each side of the avenue like rows of sentinels or pine-trees. The rear-guard of the caravan was composed of a cage with two dozing lions, behind whom plodded two baby elephants, lethargically swaying their trunks, every now and then emitting a trumpeting cry as if they were announcing the arrival of the courtly cortege …

No one uttered a word as the caravan disappeared into the weedy fields outside the town, designated by the mayor for their one-night performance.

Before the astonished eyes of the townsfolk, many of whom had rushed out to the field leaving their shops unoccupied, men, women and other ‘odd’ individuals scrambled to and thro, pitching, erecting, raising, until the top-tent loomed large and welcoming before them. Admission was a mere two dollars, a comfortable fee for the good people of Black Rock, a fee, too, considered a largesse on the part of the owners given the fact that the performers had no peer on earth … Or so they said.

At eight o’clock sharp the flaps of the big-top were flung open to the mistrustful but curious folks of Black Rock. Mayor Rip Branco, with his wife and two young boys, was the first to be admitted, then the town’s children, all to be seated in the first six or seven rows of the grandstand. Next to shuffle in were the farmers, factory workers, bankers and shopkeepers with or without their wives, conducted to the stalls flanking the grandstand. No animals were permitted. Many of the men grumbled protestations or sardonic remarks, but the ticket seller, a smiling dwarf sporting a torero costume, took no heed.

When the spectators had settled in comfortably the lights went out. A blast of music boomed out of the pitch black. Trombones, trumpets, hand-drums and tambourines filling the big-top with rhythms and melodies very foreign to the ears of the spectators. A huge spotlight fell on five or six colourfully-dressed individuals in the ring masquerading as some sort of rag-time band, blowing or banging their instruments as they danced about in happy-go-lucky abandon. The ring-master stepped out of this motley crew, pushing and shoving them aside, lashing out with his whip towards the more recalcitrant ones, who, in defiance of the snapping whip, blew out scales of disobedience. He bowed to the spectators in the most obsequious manner, doffing his black top hat. One of the musicians handed him a huge megaphone and he bellowed :

“Ladies and gents … and children too, tonight is the night of all nights, one you will never forget. All of you will witness the most rollicking merry-makers that have stalked our good earth; the most incorrigible buffoons who have ever lived. Your eyes will feast upon a jamboree of dancing, jestering and cavorting oddities whose dazzling shenanigans have always made children shriek, women scream, men doubt their senses. But I can assure you every stunt, every act, every gesture, however burlesque, is of the utmost authenticity.” Whether all the spectators were able to decipherthe ring-master’s opening tirade is difficult toassess. In any case, he went on: “ Now, let me present the strongest man on Earth, the nameless giant of Central Asia.” And as he cracked his whip the musicians fled into the darkness behind him. Out of that mysterious dark, the nameless giant charged into the middle of the arena like a raging bull. The master of ceremonies fled as if for his life. Snorting and grunting, the colossus, clad only in a tiger-skin loin-cloth, flexed his biceps, threw out his mighty chest, tightened his thigh muscles. He was indeed a mountain of muscle. Meanwhile popcorn and cotton candy were being distributed to the children, free of charge. Mayor Branco and his family also benefitted from this boon …

The strongman made horrible grimaces at the children who shrank back in their seats, squealing. He stomped about snarling and growling, flaunting his muscle-laden body until out rushed seven little dwarves dressed as toreros, all of them brandishing a bullfighter’s cape. They swarmed about the now enraged strongman, waving their capes and taunting him with obscene gestures and cuss words. The strongman charged into them head down like a bull, snorting and panting, swinging his bull-like neck from left to right, knocking a few dwarves to the sandy soil of the arena. Just as the crowd began to display overt displeasure at this unseemly spectacle with hoots and hollers (except the children who were cheering on both), two dwarves jumped up on to the strongman’s massive shoulders, followed promptly by all the rest, where gradually they formed a little pyramid atop this mountain of a man, who presently much appeased, pranced about in the spotlight with his ‘captured’ dwarves’, singing a song in some alien tongue. The dwarves hectored the dwarf-bearer, chaffing him with the crudest of names, smacking his massive face or slapping the top of his bald head with pudgy hands. With one mighty shake of the head, the strongman shook them all off into the air like so many swarms of flies, they, tumbling and rolling away, far enough from him where they continued to gesture indecorously.

Many spectators began to boo and hoot. Others laughed and cheered, especially the children, who munched happily on their cotton-candy and popcorn. “Shame! Shame!” cried out several women from the stalls. But their rebukes were drowned out by two or three applauding groups of farmers who apparently had been drinking before the performance. In fact many men were drunk, and the majority were taking much delight in this unusual spectacle …

Just then, at the crack of the ring-master’s whip, the dwarves rolled out of the arena and the strongman stomped away, bowing to the crowd. Into the ring now appeared five very weird-looking creatures, and behind them, as if by magic, a long, high tightrope that had been erected, held up by two very high wooden ladders. The spectators were baffled: humans or animals? Three, perhaps women, had faces of lions, whose ‘manes’ grew out of their cheeks, rolling in thick strands down to their feet. It was a horrible sight! But more horrible still were the two-headed and the mule-faced women, dark faces drooping down to their necks. Gasps rose from the crowd. Cries of indignation followed.

“Freaks ! Monsters!” they rasped and raged at the smiling ring-master who introduced his acrobats and trapeze performers, one by one, as the finest in the land whilst they speedily climbed up the ladders, three to the left, two to the right. At the top, they tip-toed out on to the thin wire where in burlesque abandon they danced and pranced and sang, the wire swaying to and fro. One or two juggled little red balls, tossing them over the heads of the others who attempted to catch them. Far below, the master of ceremonies whipped his whip and the merry acrobats danced and pranced all the more ardently, one or two on one foot, as the wire rocked, rolled and pitched like a boat. Terrified shrieks rose from the now standing crowd. Farmers and factory workers showed their fists. Women shouted abuse. As to the children and Mayor Branco, they clapped in rhythm to the singing quintet rocking and rolling on that tightrope.

At that point Mayor Branco turned towards the displeased crowd behind him, confused about what attitude to adopt. There was no doubt that the acrobats and trapeze performers were genuine artists ; their antics on that high wire brooked no belief of beguilement. And however ‘freakish’ they appeared to be, this awful birth-born deformity should welcome a hearty appraisal. Which the good mayor did from the bottom of his heart when the five performers had slid down the ladders, taken their bows in the middle of the ring and disappeared behind the rear flaps of the top-tent.

Much of the crowd were on its feet, red-faced (due to their drinking ?), shouting down to the ring-master as he cracked his whip violently: once … twice … thrice, signal which brought out two ferocious, roaring lions[1] shaking their manes. The spotlights followed their proud steps as they neared the front rows of the grandstands. There they sniffed the cotton candy of the now terrified children who recoiled in their seats. Their parents rushed to their rescue, but this was unnecessary, for another crack of the whip — and the accompanying spotlight — brought out a three-legged man and a pin-headed man. They strolled towards the sniffing lions, calling them by their names. One of the lions began lapping the popcorn out of the outstretched hands of several children who squealed in wary delight. Then the lion licked those charitable hands in grunting gratitude.

The pin-headed man whistled. The huge beast turned and trotted to him. He waved to the crowd then opened the lion’s mouth, pushing his pin head into it. As to the three-legged man, he had hopped on to the other lion’s back, two legs at its flanks and one lying over its fluffy mane. With a deafening yelp and roar, they galloped around the ring as if they were at a rodeo show, rushing around the pin-headed man whose whole tiny body had by now completely disappeared in that lion’s open mouth. The crowd held their breaths uncertain of the stance they should take on this stunt. Could a man possibly crawl into a lion’s massive maw ? The drunken farmers laughed grossly. Their wives sneered in contempt. The children sat in excited expectation.

Meanwhile another spotlight had fallen on a beautiful milky-white woman clad in a silken gown, standing upright against a large board placed behind her. Another spotlight swung to the left where a legless man, using his arms like a pair of crutches, had positioned himself ten or fifteen feet from the upright woman, a huge leather belt girding his chest from which hung dozens of kitchen knives. Between this scene and the lion-tamers’ antics, the spectators remained nonplussed, no longer hooting or hectoring.

The legless man swiftly took a knife and threw it at the lovely girl; it drove into the back board a quarter of an inch from the crown of her head. Here the crowd puffed in awe. Many women covered their eyes whilst the children were all eyes! He threw another and another. After each knife thrown, the crowd gasped a huge gasp! The legless man continued his act, each knife working rapidly downwards from the woman’s head, around her exquisite shoulders, along her slim, graceful hips, lengthwise her bare, slender legs until reaching those minute feet of hers. When he had finished his knife-throwing performance, the beaming, long-haired woman stepped out from the contour of the knives, the spotlight proudly exhibiting her ravishing silhouette configured on the board. With a gesture of triumph, she pointed to that silhouette, then glided over to the legless man, took him by the arm and both bowed reverently to the crowd. The men jumped up cheering wildly, either out of respect for the knife-throwing performer or for the ravishing beauty of the woman. As to their wives, they remained seated, smugly looking towards the ring, disregarding their drunken husbands’ sonorous applause. Mayor Branco was on his feet applauding along with his two boys, his wife tugging at his sleeve to sit so as not to make a spectacle of himself.

All of a sudden two spotlights swept over the galloping lion and the one that, it would seem, had all but swallowed the pin-headed man. But no ! Look … there … The lion yawned a wide yawn and out of that yawn the pin-headed man leapt, running about the ring crying out: “I’ve lost me head ! I’ve lost me head!” The crowd, stunned by these uncouth shenanigans, again began yelling insults. As to the galloping lion and its whooping cavalier, they darted to the right, where in front of them a huge hoop had been magically placed; a fiery hoop whose leaping flames hissed and sizzled. Through the hoop they jumped followed by the other lion, tailed by the waddling pin-headed man who dived through the hoop, tumbled over on the other side, got up, dusted himself off, then bowed to the hypnotised spectators. The children at once howled with joy. The adults, hesitant as to the ‘quality’ of this extravagant act, remained stoic, frowning.

The band struck up a local tune, horns and drums ushering in a motley gaggle of clowns rushing about the ring like escaped madmen from an asylum. In their frantic scuffle, two or three of them were tossing about a strange object, flinging it about like a football. A sudden shiver of horror swept through the crowd: those merry-making buffoons were passing a living torso to one another! A man without arms or legs! He had a huge smile on his face as he sailed in the air from one pair of arms to another. Then the clowns broke into a song: “ Zozo the clown and his funny hat, patches on his pants and he’s big and fat, long flappy shoes and a round, red nose, makes people laugh wherever he may go!” These lyrics were repeated without respite as they played football with the torso, who, and it must be stated here, was crying out for joy!

Enough was enough! “ Monsters! Monsters!” cried out groups of red-faced, infuriated men from the back of the stalls, screwing up their eyes. Rotten tomatoes were thrown at the shameless buffoons by the farmers who had brought them along for the occasion. Ladies screamed. The children sat in dazed awe, following each pass of the laughing torso as if they were following a football match. The frolicking clowns, undismayed by the tomatoes, performed cartwheels and somersaults from one end of the ring to the other.

But it was the following scene that left the crowd dumbfounded. As the laughing torso was thrown from clown to clown, spurts of orange flames spouted from his mouth! Long fiery flames that carved out tunnels of blazing light as he arched high in the air. This surreal scene rendered the crowd, momentarily, mute with puzzled, ambiguous emotions. They soon, however, regained their initial, infuriated state.

In the last rows of the stalls, rowdies were making a tremendous row, brawling with the bankers and notaries who had shown, up till then, an impassioned interest in these performances. Fisticuffs broke out. Faces were slapped or punched. Hair and beards were pulled. Clothes torn. Ladies knocked over. Things were indeed getting out of hand. Whistles blew. The local security guards rushed into the upper stalls roughly handling the more pugnacious men, untangling the tangles of rioters one by one, unknotting the knots of brawlers that rocked the stalls.

At that stormy moment, trumpets, trombones, drums and cymbals sounded below, silencing the brawlers for a brief moment. Then from out the side flaps two baby elephants charged, trunks held high, trumpeting louder than the fanfare! Atop them, seated in howdahs apparelled in the most royal regalia were yelping mahouts fitted out in cowboy costumes, waving their huge cowboy hats at the now stupefied spectators. The elephants chased the clowns around the ring, grabbing a few with their trunks, rolling them up then flinging them into the air. The elephants had gone amok, lifting their trunks for all to see their huge flabby smiles. The living torso was passed high over the mahouts’ reach, mouthing furious flames galore, landing with a thud in the arms of a receiving clown on the other side. The children in the front rows were on their feet howling with merriment, laughing along with the clowns and elephants as the chase continued on its merry-go-round way. And here the band struck up a favourite tune to which all the clowns sang: “Zozo the clown and his funny hat, patches on his pants and he’s big and fat, long flappy shoes and a round, red nose, makes people laugh wherever he may go.”

This boisterous chorus was joined by children, some of whom had internalised the tune. Their voices rose in unison, rising far above the brawling, bickering and rioting behind them in the upper stalls. To tell the truth, some of the farmers, factory workers and bankers had also joined in the singing. How they enjoyed those yelping ‘cowboys’ whooping it up atop the baby elephants.

Mayor Branco sized up the maddening bedlam, reluctant to decide who were the madder: the performers or the crowds! Yet, deep down, oh how he was enjoying himself that evening. For him, it would be the most memorable night of his life. And I will add here, for most of the other good folk of Black Rock, be they the howling children, the appalled women or the obdurate men …The madness grew even madder when from out of the side flaps the seven little dwarves scrambled, dashing up to the elephants, waving their capes. One or two of these mischievous acrobats had been on stilts and were trying to distract the rampaging mahouts with their capes. The mahout-cowboys riposted by letting fly their lassoes, the nooses catching one or two of the rascally dwarves who were toppled from the stilts and dragged mercilessly in the wake of the plodding elephants. The ring had become a veritable pandemonium of lunacy and delirium …

Suddenly all the spotlights went out. A sudden lull crept over the ring, creeping stealthily up into the stands. A deep lull during which time not one drunken cry from the adults, not one choking laughter from the children, not one trumpet from the elephants nor yelp from either the cowboy-mahouts or clowns or dwarves were heard. The lull must have lasted a minute or two …

The lights suddenly flooded the ring where all the performers and animals had mustered in humble expectancy. Silently they stood (or were held!) searching out the crowd for compassion, understanding, appraisal. The master of ceremonies stepped out from amongst them. He doffed his top hat :

“Ladies, gents and children. The performances that you have experienced tonight will not go unnoted in the chronicles of Black Rock.” (Whether this opening remark meant to be ironic is not for your narrator to say. In any case, it provoked a few snickers from the upper stalls.) “Yes, many of you have exhibited displeasure and resentment. Monsters you cry out? Freaks you bellow in bitter tones! Well, yes, if by monsters you mean these humble unfortunates who have had the courage to show themselves, to exhibit themselves to the public as true artists, and not sulk in self-pity or hide out like criminals or unwanted wretches out of the righteous eye of the public. But why display such ill-feelings towards them, may I ask? Because many of my performers suffer from birth deformities? Because they are physically unlike normal people? No! Their terrible deformities do not, and will never deprive the public the goodness and nobleness of their hearts of gold … their feelings of sincerity when performing for you. But this sincerity must be reciprocal. If not, their disfigurement will be interpreted as a ticket to the streets, a paid fare for lethal medical experiments in clinics, tearful departures for the zoos where they will be put into cages like savage animals … We are a grand and hard-working family whose every member holds equal status. But their livelihood, ladies and gents, depends on your good will, your protection against dangerous individuals whose illicit, murderous intentions would have killed them off long ago or maimed them even more. Here, within the sanctuary of this vast tent, look not at those deplorable disfigurements, but consider fairly and honourably their long, long hours of labour, their unquestionable talent, their dauntless courage and human dignity.”

The fanfare struck up one of rag-time tunes to whose familiar melodies all the children stamped and clapped. Their mothers and fathers also clapped. Farmers, shop-keepers, bankers and factory workers alike imitated the gaiety of the children. Even the security guards joined in the revelry. As to those adamant hooters and rioters, they stalked out of the top-tent, raising their fists, spitting out drunken obscenities … Which were drowned out by the general mirth and merriment.

All the performers bowed. The baby elephants held their trunks high, the lions shook their proud, bushy manes. With the crack of the whip the lights went out.

The good folk of Black Rock Montana filed out of the top-tent singing the Zozo tune. Mayor Rip Branco was the last to leave, a bright, beaming smile on his round face.

And as Shakespeare once had occasion to record: All’s well that ends well.

[1] The story is set in indeterminate times (the author claims around 1970s) before animals were banned from performing in circuses.

https://www.fourpawsusa.org/campaigns-topics/topics/wild-animals/worldwide-circus-bans

.

Paul Mirabile is a retired professor of philology now living in France. He has published mostly academic works centred on philology, history, pedagogy and religion. He has also published stories of his travels throughout Asia, where he spent thirty years.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International