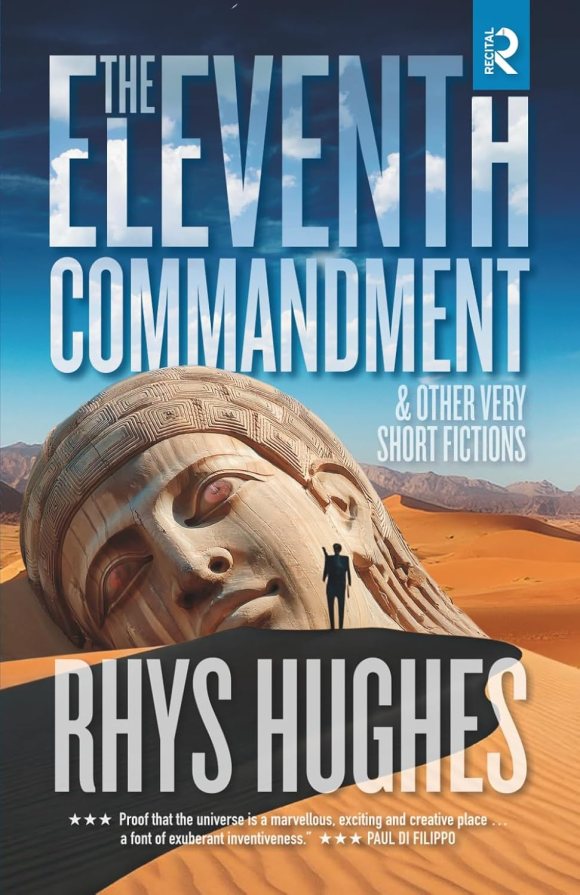

Title: The Eleventh Commandment And Other Very Short Fictions

Author: Rhys Hughes

Publisher: Recital Publishing

Taurus

“What sign do you think the minotaur is?”

This was an unexpected question from above. I turned my head and saw him three floors above, leaning out of his window. I was watering the flowers in their boxes on the balcony and I stood up slowly and stretched. Then I paid serious attention to the question and finally said, “Taurus.”

He nodded. It was the obvious answer, but his nod was ironic and it was clear he was disagreeing with me. It occurred to me that maybe the body of the minotaur and his head would have different birthdays and be born under two different signs, but I was in no mood for riddles and shrugged.

“Do you suppose he was attracted to women or cows?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“The minotaur! Were his amorous desires determined by his human mind or his bovine physicality? I can’t work it out.”

“You seem very interested in the details of his life.”

“Don’t be absurd, he never lived.”

“Yes, he was a myth only.”

“Nonetheless, he was born under the sign of Taurus.”

“But that’s what I said earlier.”

“Oh, did you? I misheard. I thought you said ‘torus’, which as we both know is a geometrical shape and not a zodiac sign.”

My neighbour was a joker, of this I was certain now. I wondered why we hadn’t interacted until this moment. I spend a lot of time on my balcony and he must have seen me there. I leaned on the railings and looked down on the city. The old alleys and narrow streets were like a maze. The thread that would lead a lost traveller out again was made from air, only the wind.

It was perfectly possible for the minotaur to have escaped the labyrinth by chance, from wandering at random, and in this case Theseus would have found it empty when he ventured inside, but for the sake of saving face his story wouldn’t change. Nobody could dispute that he slew the creature. Yet the monster was free, making his way in a world where he must always be alone.

No woman could want him, nor any cow. Never settling down, he would voyage to the edge of the known world and who can say what he would do when he reached it? Sit on his haunches and wait, I guess.

My neighbour had a man’s head, not that of a bull, so he couldn’t be the minotaur, as I briefly suspected when he asked me a third question, “Who does he support in a bullfight, the beast or the matador?” and I said, “The answer depends less on the fact he’s a hybrid than on his sense of justice.”

“Meaning what exactly?”

“Anyone with a sense of justice supports the bull.”

“I am his descendant, you see.”

“How is that feasible?”

“Somewhere on this remarkable planet of ours he must have met a woman with a cow’s head. Over many generations the bovine aspects weakened. All that remains is my unusual stomach. I don’t complain.”

Before I could raise an objection, he added wistfully:

“A shame I don’t exist.”

In the Den with Daniel

Daniel Day-Lewis is the best actor in the world. You know this. Everyone else knows this. Your wife knows it when you kiss her on the cheek before you set off for work. Your fellow commuters know it on the underground train that is always crowded at this time of the morning. Your colleagues in the office know it when you arrive. When you sit at your desk and switch on your computer you can’t imagine how the simple truth could be different. He is the best actor in the world. There can be no argument.

He is more than an actor and this is why he is so magnificent. He inhabits his roles, he refuses to regard the characters he plays as separate from himself. He becomes those characters, absolutely without doubt or hesitation. He puts aside his own identity for the duration of the making of a film. He lives his role, no matter how uncomfortable, even when cameras aren’t rolling. This is the supreme commitment to an art form and you admire him immensely. We all admire him. He is a marvel, a genius.

Whether he is playing a dramatic villain in remarkable circumstances or an ordinary man in an everyday situation, he is utterly convincing, not only to his fellow actors and the audiences of cinemas, but even to himself. When he plays a role, the role vanishes. The character is suddenly real, no less solid than I am. I am strolling the office floor today, chatting with the employees. I do this from time to time, to make them feel at ease. I approach your own desk. You swivel your chair and wait for me to speak.

“You have a wife, a child, a mortgage on a house. I have been asked by my superiors to make cuts to the workforce. I don’t wish to do this. I know it will be difficult for any employee who is forced into redundancy. But I have my quota to fulfil. Jobs will be lost. You need to prove that you are invaluable. That is the only way you can secure your future here. Do you understand? Prove you are irreplaceable. Do this for me. Be irreplaceable, I am begging you. Please don’t make it easy for me to dismiss you.”

And you nod, but I see in your eyes that you have given up. At the end of the day, you rise from your desk to begin the journey home. You are descending the stairs and hear the words, “Finished,” from above. Suddenly you remember that you are Daniel Day-Lewis, that your office job is fictional, the woman you call your wife is a fellow actor, your child doesn’t exist. It was an act all along, brilliant, inspired, relentlessly perfect.

But you wonder. How can you be certain that Daniel Day-Lewis himself isn’t just a character in another film?

Beyond the Edge

A man was crouching on the path that runs along the side of the river, and as I approached him I saw he was moving a chess piece in the dust. It was a white knight. I was almost on top of him before he paused and turned to look up at me. Then I asked him what he was doing and he replied that he was playing a game of boardless chess. It had started in a distant city on a regular board, like most chess games, but frustrated with the limited area on which the entire struggle was expected to progress, he had agreed with his opponent to allow pieces to move beyond the boundary squares when necessary. And that is what had occurred.

“My knight kept going,” he added, “off the edge and along the streets and out of the city, and I didn’t have a desire to turn him around and head back to the board. So here we are, and the game continues, or at least I’m assuming it does, many years later. My opponent might have resigned by now and gone home; or he may have captured my king in my absence and defeated me without me knowing; or he too could be wandering the world with a piece in his hand, moving it across the invisible squares of the land until a stranger stops to ask him about it.”

I laughed and bade him have a good day, then I rode around him with due care and cantered towards the small town I saw looming ahead, milky smoke issuing from the chimneys of its houses. As I entered the town and reached the main square, I saw two men playing chess outside a café, and I wondered what might happen if the white knight also came this way and became involved in their game, an unexpected and accidental ally to one side, capturing black pieces as it wandered across the board. The incident could incite a real fight between these players and the newcomer, a three-way battle that would mean broken teeth.

If only that migrating knight was half black and half white, like many actual horses in the world, bloodshed could be avoided. A piebald chess piece is surely neutral. I was tempted to return to the river path and warn the fellow of the hazard ahead, but I had vowed never to retrace my steps. I was fleeing a battle and I too was a knight that had ventured beyond the edge of his board and kept going. Unlike the man crouched in the dust, I had taken precautions, for I had stopped at an abbey and bought a flagon of the darkest ink from the brothers in the scriptorium and had painted on my white stallion the stripes of salvation.

About the Book

Rhys Hughes’ unique observational, aphoristic humour abounds in this collection of artfully crafted, extremely short stories. A perennial master of invention, Hughes explores our perceptions of humanity, mining truths beneath the clutter of culture with incisive wordplay and trademark wit.

Hughes has arrayed eighty-eight narrative gems into three groups, The Zodiacal Light, Beyond Necessity, and The Ostraca of Inclusion-clever new takes on mythology, history, and science. A thirteenth star sign, minotaurs and gorgons, a dog ventriloquist, gears and cogs, a clock-wrestling octopus — all are semantic Möbius strips where fantasy and philosophy are seamlessly melded as only Hughes can do; both thought provoking and entertaining.

About the Author

Rhys Hughes was born in Wales but has lived in many different countries. He began writing at an early age and his first book, Worming the Harpy, was published in 1995. Since that time he has published more than fifty other books and his work has been translated into twelve languages. He recently completed an ambitious project that involved writing exactly 1000 linked short fictions. He is currently working on a novel and several new collections of prose and verse.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International