The Great War is over

And yet there is left its vast gloom.

Our skies, light and society’s soul have been overcast…

'The Great War is Over' by Jibanananda Das (1899-1954), translated from Bengali by Professor Fakrul Alam.

Jibanananda Das wrote the above lines in the last century and yet great wars rage even now. As the world struggles to breathe looking for a beam of hope to drag itself out of the darkness induced by natural calamities, accidents, terror attacks and wars that seem to rage endlessly, are we moving towards the dystopian scenario created by George Orwell in 1984, which would be around the same time as Jibanananda Das’s ‘The Great War is Over’?

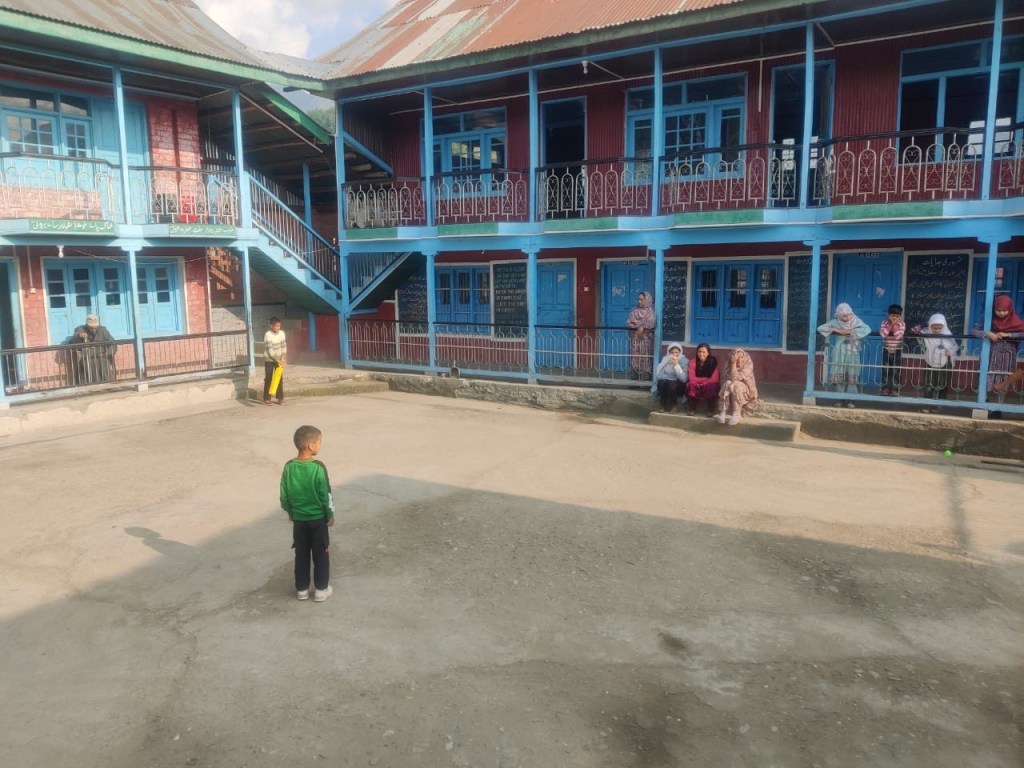

Describing such a scenario, Ahmed Rayees writes a moving piece from the Kashmiri village of Sheeri, the last refuge of the displaced refugees who were bombarded after peace was declared in their refuge during the clash across Indo-Pak borders. He contends: “People walked back not to homes, but to ruins. Entire communities had been reduced to ash and rubble. Crops were destroyed, livestock gone, schools turned into shelters or craters. How do you rebuild a life when all that remains is dust?”

People could be asking the same questions without finding answers in Gaza or Ukraine, where the cities are reduced to rubble. While we look for a ray of sunshine, amidst the rubble, Farouk Gulsara muses on hope that has its roots in eternity. Vela Noble wanders on nostalgic beaches in Adelaide. And Meredith Stephens travels to the Australian outback. Devraj Singh Kalsi brings in lighter notes writing of driving lessons while Suzanne Kamata creeps back to darker recesses musing on likely ‘criminals’ and crimes in her neighbourhood.

Lopamudra Nayak writes on social media and its impact while Bhaskar Parichha writes of trends that could be brought into Odia literature. What he writes could apply well to all regional literature, where they lose their individual colouring to paint dystopian realities of the present world. Does modernising make us lose our ethnic identity and how important is that? These are questions that sprung to the mind reading his essay. As if in an attempt to hold on to the past ethos, Prithvijeet Sinha wafts around old ruins in Lucknow and sees a cemetery for colonial soldiers and concludes: “Everybody has formidable stakes, and the dead don’t preach the gospel of victory or sombre defeat.”

Taking up a similar theme of death and war is a poem from Saranyan BV. In poetry, we have colours from around the world with poems from Allan Lake, Ron Pickett, Ananya Sarkar, George Freek, Jim Bellamy, Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Juairia Hossain, Gautham Pradeep, Jenny Middleton, Mandavi Choudhary and many more. Multiple themes are woven into a variety of perspectives, including nature and environment, with June hosting the World Environment Day. Rhys Hughes gives a funny poem on the Welsh outlaw, Twm Siôn Cati.

We have mainly poetry in translation this time. Snehaprava Das has brought to us Soubhagyabanta Maharana’s poems from Odia and Ihlwha Choi has translated his own poem from Korean. Sangita Swechcha’s poem in Nepali has been rendered to English by Saudamini Chalise. From Bengali, other that Jibanananda Das’s poems translated by Professor Fakrul Alam, we have Tagore’s pensive and beautiful poem, Sonar Tori (the golden boat). Yet another Bengali poet, one who died young and yet left his mark, Sukanta Bhattacharya (1926-1947), has been translated by Kiriti Sengupta. Sengupta has also translated the responses of Bitan Chakravarty in a candid conversation about his dream child — the Hawakal Publishers. We also have a feature on this based on a face-to-face conversation, giving the story of how this publishing house grew out of an idea. Now, they publish poetry traditionally, without costs to the poet. Their range of authors are spread across continents.

Our fiction again returns to the darkness of war. Young Leishilembi Terem has given a story set in conflict-ridden Manipur from where she has emerged safely — a story that reiterates the senselessness of violence and politics. While Jeena R. Papaadi writes of modern human relationships that end without commitment, Naramsetti Umamaheswararao relates a value-based story in a small hamlet of southern India.

From stories, our book excerpts return to the real world, where a daughter grieves her father in Mohua Chinappa’s Thorns in My Quilt: Letters from a Daughter to Her Father while Wendy Doniger’s The Cave of Echoes: Stories about Gods, Animals and Other Strangers, dwells on demystifying structures that create borders. We have two non-fiction reviews. Parichha writes about David C Engerman’s Apostles of Development: Six Economists and the World They Made. And Satya Narayan Misra discusses Bakhtiyar K Dadabhoy’s Honest John – A Life of John Matthai. Somdatta Mandal this time explores a historical fiction based around the founding of Calcutta, Madhurima Vidyarthi’s Job Charnock and the Potter’s Boy while Rakhi Dalal looks at fiction born of environmental awareness, Dhruba Hazarika’s The Shoot: Stories.

We have more content. Do pause by our contents page and take a look.

Huge thanks to all our contributors without who this issue would not have materialised. Heartfelt thanks to the team at Borderless for their support, especially Sohana Manzoor for her iconic artwork that has almost become a signature statement for Borderless.

Let’s hope that next month brings better news for the whole world.

Best wishes,

Mitali Chakravarty

Click here to access the contents for the June 2025 Issue

READ THE LATEST UPDATES ON THE FIRST BORDERLESS ANTHOLOGY, MONALISA NO LONGER SMILES, BY CLICKING ON THIS LINK.