Ratnottama Sengupta tracks the journey of Leslie Carvalho over a quarter century

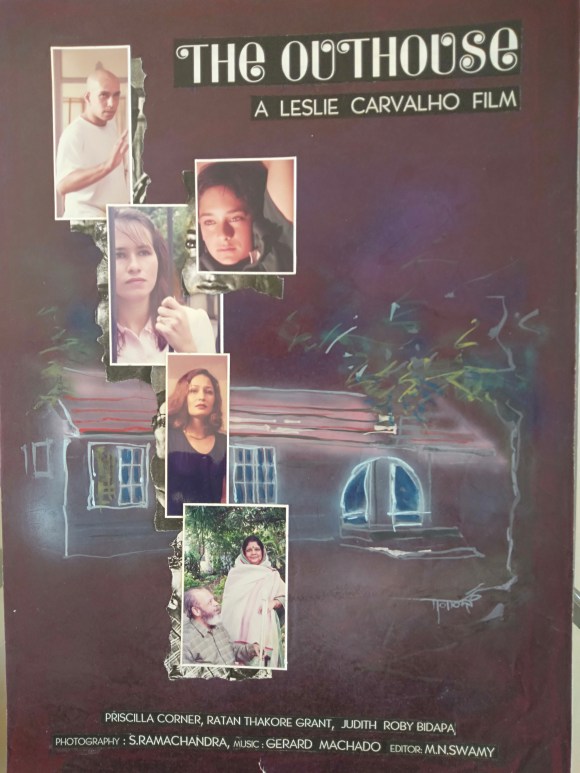

It seems like only the other day. The International Film Festival of India, IFFI, 1998 was on. Along with a colleague, I was seated on the steps outside Siri Fort I auditorium connected to a long corridor going to Siri 2. Someone introduced Leslie Carvalho. “Aha! The young filmmaker from Mangalore?” I responded. “There’s a write up on you in The Times of India today. It says there’s a lot of expectation from The Outhouse.”

The “delightfully sweet” film had lived up to the expectation of the critics. It was bestowed the Aravindan Puraskaram, presented by the Kerala Chalachitra Film Society to commemorate the iconic Malayalam director, and the first Gollapudi Srinivas award, another national level award to recognise filmmakers marking their debut in Indian cinema. So I was not surprised to meet him next as a co-member of the jury for the National Film Awards 2000.

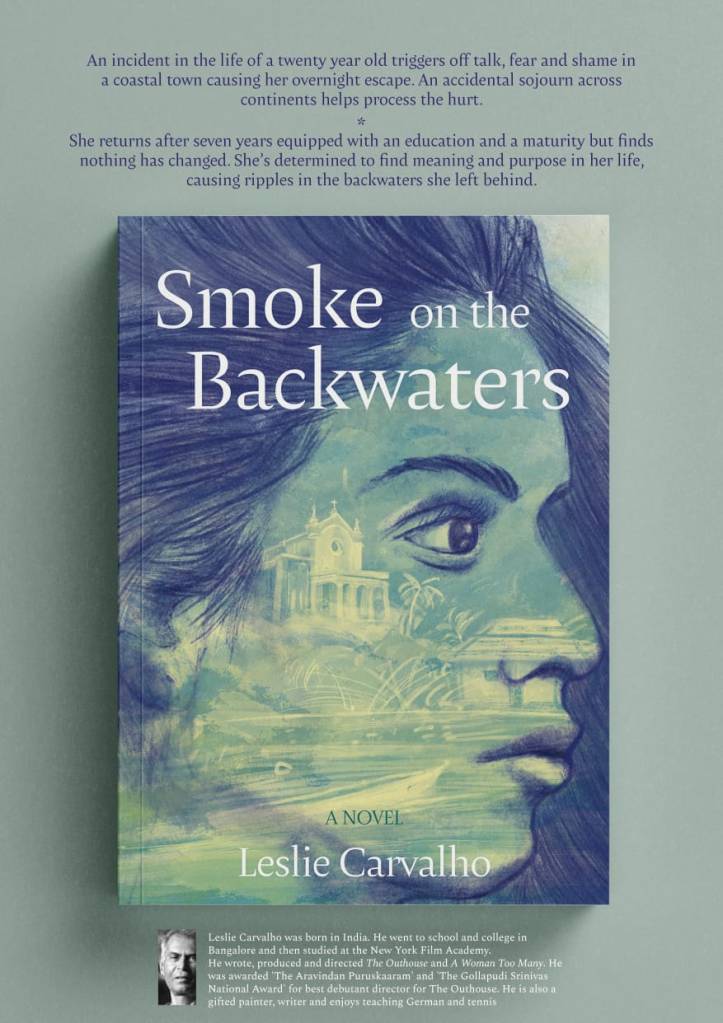

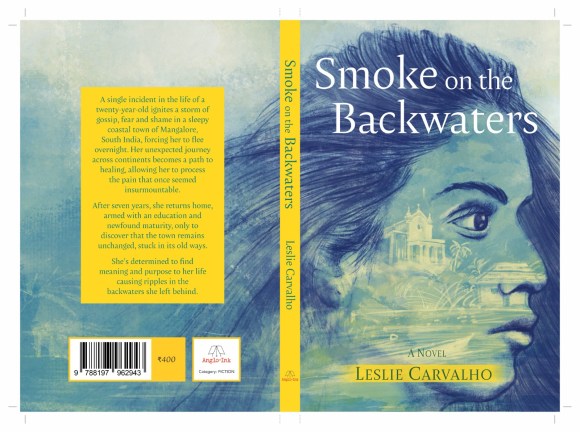

The Tennis coach who is also a German language teacher with a passion for painting has now published his first novel, Smoke on the Backwaters. It centres on Rosa, a twenty-year-old from Mangalore, who is forced to flee overnight because of the storm of gossip, fear and shame unleashed by a single incident in her life. Her unexpected journey across continents becomes a path of healing. Seven years later, armed with education and maturity, she returns home, determined to pursue her purpose in life. But how much had the town she left altered from its old ways?

RS: Leslie, before we talk Backwaters, can we briefly revisit The Outhouse? From where did you derive its content? And what was your compulsion for choosing that subject?

LC: The Outhouse was a simple, linear narrative about moving on in life despite the odds. A young mother’s need to gain economic independence to supplement the family income; the help she received from her financially independent sister; a kind hearted Bengali landlady’s generosity which causes stress and violence in the Anglo-Indian couple’s day to day life, and how it affects the two children growing up.

RS: Why did you choose this subject as your debut vehicle? If you were to travel in a time machine, would you choose a ‘mainstream’ subject?

LC: I chose this subject as my debut vehicle as I had seen quite a bit of violence in the Anglo- Indian community in the Lingarajapuram area of Bangalore I grew up in.

I was itching to make a movie after my six-month course at the New York Film Academy. As I was working on a very tight budget, I just stuck to what was taught — to keep it simple, straightforward and just tell a story using the various tools of cinema — in short, to make it cinematic.

If I were to go back in time, I don’t think I would have chosen a ‘mainstream subject’. I derived immense satisfaction along with the cast and crew as we felt we were working on something we were passionate about. We all felt drawn towards the characters, the story and the theme of the film.

RS: How did you get interested in cinema? And what were the problems you faced while filming The Outhouse – in terms of funding, casting, shooting location, distribution?

LC: I grew up watching Tamil, Kannada, Hindi, a couple of Konkani and lots of Hollywood films. My mother tailored clothes at home, and she taught a whole lot of women stitching. They were fans of Tamil cinema, especially of Sivaji Ganesan, MGR, and the heroes of Kannada cinema, Dr. Rajkumar and Vishnuvardhan. She also enjoyed the Hindi films of Rajesh Khanna, Dharmendra, Hema Malini, Amitabh Bachchan, Sanjeev Kumar, Jaya Bhaduri and Rekha — that is the popular cinema.

And my father, being an Army person, took us to see English films, like The Ten Commandments, The Bible, Hatari, To Sir, With Love[1]. Also, St. Germain’s School where I studied, screened English films every Friday afternoon in the Hall, from spools off a projector that made a jarring sound. It was an amazing experience — black and white Charlie Chaplin, Laurel & Hardy films and also Patton with all the bad words. Later, when in college, we would bunk classes to watch most of the popular Hindi and English movies.

At the New York Film Academy, I was exposed to an entire range of the world’s best in cinema. Satyajit Ray, Akira Kurosawa, Ingmar Bergman, Antonioni, John Ford, William Wyler, Fellini, Jean Renoir… And I watched a whole lot of films on the American Movie Chain (AMC). There I discovered all of Spencer Tracy’s films and fell in love with his sense of timing and under playing. It was also a time when I discovered Guru Dutt and marveled at his brand of filmmaking from Pyaasa, Kaagaz Ke Phool, Chaudhvin Ka Chand, Sahib Biwi Aur Ghulam to Aar Paar and Mr & Mrs 55[2].

It is hard to believe I began the shoot for The Outhouse on September 18, 1996, and completed it in 14 days – on October 1. After we went through the rushes, we required two more shots to link the gaps. Since I was on a shoestring budget of a few lakh rupees, I had rehearsals with the cast for close to three months. I doff my hat to them in gratitude as 90% of the film was canned on first takes. I could not afford retakes, and I worked with a brilliant cameraman, S Ramachandra, who was very supportive and encouraging. He shot most of B V Karanth, Girish Karnad, and Girish Kasaravalli films as well as the popular tele-serial Malgudi Days[3]. A number of first-time directors like myself, had benefitted immensely by his generosity and patience.

Since it was an independent film, whatever little finance I had, I sunk into the film. And then it took me a year to complete post-production for lack of finance.

I was particular about the casting. I wanted the Anglo-Indian look, feel, mannerisms, costume, interiors to be authentic. I met each cast member and spoke to them at length about the vision I had for my film. Almost all of them were from the Bangalore English Theatre, and all of them were cooperative. Moreover, Cooke Town is a quaint little place with many English bungalows and outhouses. After some struggle, I found one on Milton Street which suited my story perfectly.

After The Outhouse was selected for the Indian Panorama in IFFI ’98 and received the two national awards, I just walked into Plaza Theatre on MG Road in Bangalore and met the owner, Mr Ananthanarayan. He had heard about the film and asked me to meet the distributor, Nitin Shah of Hansa Pictures in Gandhi Nagar, the biggest distributor of English films. He put it on for a noon show for three weeks while Fire was on for the matinee and evening shows. The distributor then put it in Mangalore and Udupi for a week. And when I received the Gollapudi Srinivas National Award in Chennai, Aparna Sen was one of the honoured guests. She saw a small portion of the film and said that she would speak to Mr Ansu Sur to screen it at Nandan in Kolkata — founded by Satyajit Ray to help screen small independent films. A theatre owner in Kolkata recommended a person who took the film to the North East. It was also screened in parts of Kerala.

Coincidentally, this April 30th, The Outhouse will be screened in the leafy neighbourhood of Cooke Town next to the outhouse where the film was shot.

RS: In the last 50 years we have seen films by directors like Aparna Sen, Ajay Kar, Anjan Dutt. Even before these, Ray had touched upon Anglo Indians in Mahanagar. These are all films made in Kolkata. Is it because this is the erstwhile capital of the Raj?

LC: Many of the films on Anglo-Indians were based in Calcutta. It was the influence of the British Raj and its culture that was so much a part of their long history of ruling there. Of course their influence was in other parts of the country as well like Madras, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Whitefield and Kolar Gold Fields, the railway colonies all over the country, the hill stations, and many other cities which has pockets of Anglo-Indians.

RS: I remember one Hindi film, Julie that had an Anglo-Indian protagonist. How has the community been projected in popular culture? Was it lopsided or biased?

LC: Throughout our film history Anglo-Indians have played bit roles here and there. Some significant roles came their way in Bhowani Junction, the teleserial Queenie, 36 Chowrighee Lane, Bow Barracks Forever, Bada Din, Cotton Mary, The Outhouse, Saptapadi, Mahanagar, Julie, and Calcutta I’m Sorry[4].

Some of the characterisations have been quite biased; some not well fleshed out; some in passing fleeting moments of drunkenness, prostitution. The song and dance sequences have not helped the community, sadly.

RS: What led you to writing? The screenplay for The Outhouse?

LC: I wrote the screenplay of The Outhouse on plain A4 sheets of paper, on both sides. This is not done but I did it to save on cost. I gave the screenplay to my cinematographer S. Ramachandra, and in his generosity he understood my purpose. I went by what was taught at the New York Film Academy. Of course, I had to combine all the elements to make it whole. The idea of the screenplay came to me while I was at the film school in 1995.

RS: What was the trigger for writing Smoke in the Backwaters?

LC: As an artist, filmmaker, and writer, I have tried to combine all the elements of story-telling – fact and fiction — keeping in mind the flow of ideas, pace and momentum to engage and interest my audience and readers.

I remember beginning to write the novel two decades ago when my mother — who studied in Kannada medium — said, “I hope you will write it in simple English so I can read it too.”

And I wanted it to be reader friendly with regard to the font size, the brightness of the paper, the spacing, the clarity and the size of the book. I was lucky my publisher ‘Anglo-Ink’ was supportive and combined well to find that centre.

RS: How are you marketing the book? Through Litfests? Bookstore readings? Airport bookstalls? A H Wheelers?

LC: Since Anglo-Ink is a small-time publisher, we’ve had a dream launch in my hometown Bangalore at the Catholic Club. My book seller is Bookworm on Church Street in the heart of Bangalore and for people in Cooke Town it is in The Lightroom’ library.

We are looking at launches in various cities as well, through book readings, LitFests, Airport book stalls, AH Wheelers, readings at schools and colleges.

Since a major portion of the novel is set in Germany, we are looking at translating it into German. I hope to get it translated in a few Indian languages as well.

RS: Since the sunset decade of 1900s, Anglo Indians have been migrating to Australia and Canada. What triggered this migration? Economics or politics?

LC: The migration of Anglo-Indians was inevitable. It was bound to happen for reasons more than one, be it political, economic or social. First under the ‘Whites Only’ policy, many fair skinned Anglo-Indians migrated — the brown and dark skinned were left behind. Slowly they opened up and even they left. Some felt they would adapt better to a western culture, and have adopted their new country as their homeland.

RS: You were a big support for me when my son joined NLSUI in 2000. Again, when I curated Anadi, the exhibition of paintings by Contemporary and indigenous artists from MP and Chhattisgarh. Bangalore has since become an international megalopolis. How has life changed for the locals?

LC: Bangalore has changed dramatically and drastically. The change was bound to happen because of its growing prominence of an International City. The IT industry brought jobs, slowly other industries, started picking up from real estate, fashion, digital technology and social media platforms, start-ups, academics, sports, games, recreational and tourism.

The moderate climate was a huge bonus that attracted people from all over. Bangalore has always been cordial, encouraging and accommodative of people from all over through their mild manners, hospitality and gentleness.

Today Bangalore is unrecognisable. Still, some pockets retain that old world charm of neat, clean and green Bengaluru from the old Pensioners Paradise of Bangalore.

.

[1] The Ten Commandments (1956), The Bible (1966), Hatari (1962), To Sir, with Love (1967)

[2] Pyaasa (Thirsty, 1957), Kaagaz Ke Phool (Paper flowers, 1959), Chaudhvin Ka Chand (The Full Moon, 1960), Sahib Biwi Aur Ghulam (The Master, the Wife and the Slave, 1962), Aar Paar (This shore or that, 1954), Mr &Mrs 55 (1955).

[3] From 1986 to 2006.

[4] Bhowani Junction (1956), TV miniseries Queenie (1987), 36 Chowrighee Lane (1981), Bow Barracks Forever (2004), Bada Din (1998), Cotton Mary (1999), Saptapadi (Seven Steps, 1981), Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963), Julie (1975), and Calcutta I’m Sorry (2019)

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International