Book Review by Rakhi Dalal

Title: Never Never Land

Author: Namita Gokhle

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Namita Gokhale is a writer and a festival director. Her work spans various genres, including novels, short stories, Himalayan studies, mythology and books for young readers. She is the author of twenty-three works of fiction and non-fiction, including the novels Paro: Dreams of Passion, Shakuntala, Jaipur Journals, Things to Leave Behind and The Blind Matriarch; and the edited anthologies Mystics and Sceptics: In Search of Himalayan Masters, Himalaya: Adventures, Meditations, Life (with Ruskin Bond), and (with Malashri Lal) In Search of Sita, Finding Radha and Treasures of Lakshmi. Gokhale is the recipient of several awards, including the Sahitya Akademi Award (2021). She is the co-founder and co-director (with William Dalrymple) of the famed Jaipur Literature Festival.

At the outset, Namita Gokhle’s Never Never Land seems conventional, centering on the protagonist’s quest for meaning amidst loneliness in a bustling city life, where relationships and even “monsoon is a betrayal”. What sets this book apart is the imperative nostalgia of both lived and unlived experiences that permeate through the narrative. The author captures the nostalgia well with her style which skilfully moves between a first and third person narrative, navigating between the past and the present, with the principal character embarking upon a journey back to her roots.

The protagonist, Iti Arya, is a single, middle-aged freelance editor/ writer struggling to find a footing in her life. Undetermined about her writing which doesn’t seem to take off, she decides to return to The Dacha, a place of her childhood, in the hilly Kumaon region, where life for her had been beautiful if not downright perfect. It was a place she had longed for while living in dusty Gurgaon surrounded by a concrete forest, a place she hoped to return to find herself, a place where she could find meaning in relationships, a place where validation for who she was and what she strove for ceased to exist. ‘Never Never Land’ seems to be for her, both a literal and symbolic place of return.

Iti returns to her grandmother with whom she has spent the happiest days of her school life, her Badi Amma who used to tell her that when mountains speak, one must listen carefully. She returns to find out the stories that she can only find in the mountains. At Dacha, the cottage owned by a hundred and two years old Rosinka (her amma’s erstwhile employer), she also comes across Nina, around whom an aura of secrecy hovers. The course of the novel then ripples with their interactions providing contexts for Iti’s quest forth. At times, she is awash by the unspoken love of her Badi Amma and Rosinka, feeling secure in their presence and in the knowledge of their affection for her and for each other, an unlikely friendship that is stronger than any relationship she has known. Her stay there makes her re-examine her life to find the missing pieces that lead her to feel lonely and uncomfortable.

An inheritance, a theft, a strange recovery in a deluge, and an unfolding of a truth later, make Iti come face to face with her reality. She makes peace with memories of her now departed mother whom she did not love but wished to be seen by. She holds onto her Badi Amma and Rosinka whom she dreads to lose. She holds onto the place that makes her feel protected. A place she belongs.

The essence of the book lies in the warm relationship shared by the women whose stories are uncovered layer by layer. Women, who lonely in their own ways in life, find comfort with each other and stand guard of each other’s happiness. Reading the book reminds one of the likes of Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, only that here women are not bound by blood but by an understanding that has come with years of living together for one reason or another.

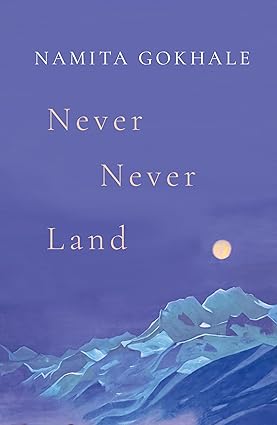

The cover page of the book, inspired by Nicholas Roerich’s painting ‘Himalayas — the Abode of Light’, resonates with Iti’s journey towards clarity and finding a meaning that illuminates her life. At the end of the monsoon, as the sun comes out, she feels revived and willing to carry on, with herself, her grandmothers and the mountains.

Rakhi Dalal is an educator by profession. When not working, she can usually be found reading books or writing about reading them. She writes at https://rakhidalal.blogspot.com/ .

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International