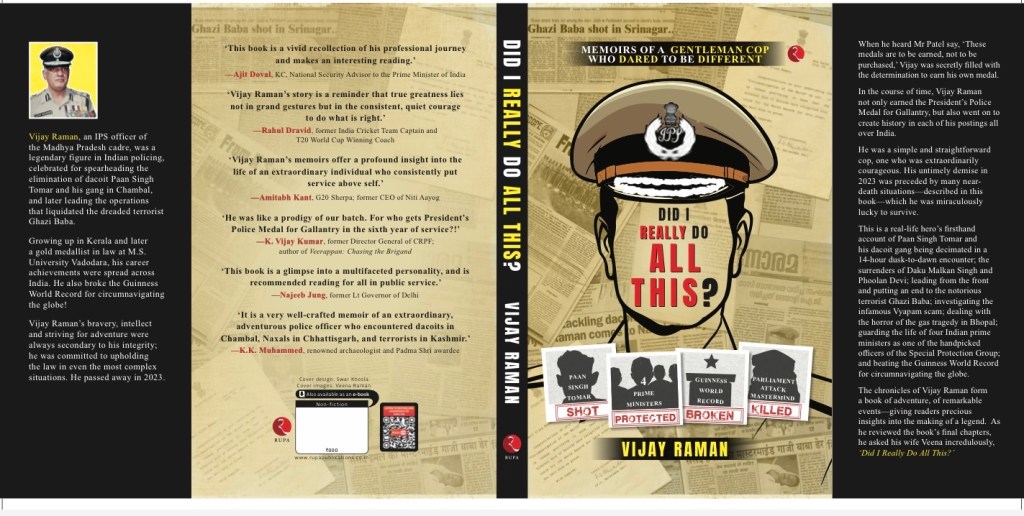

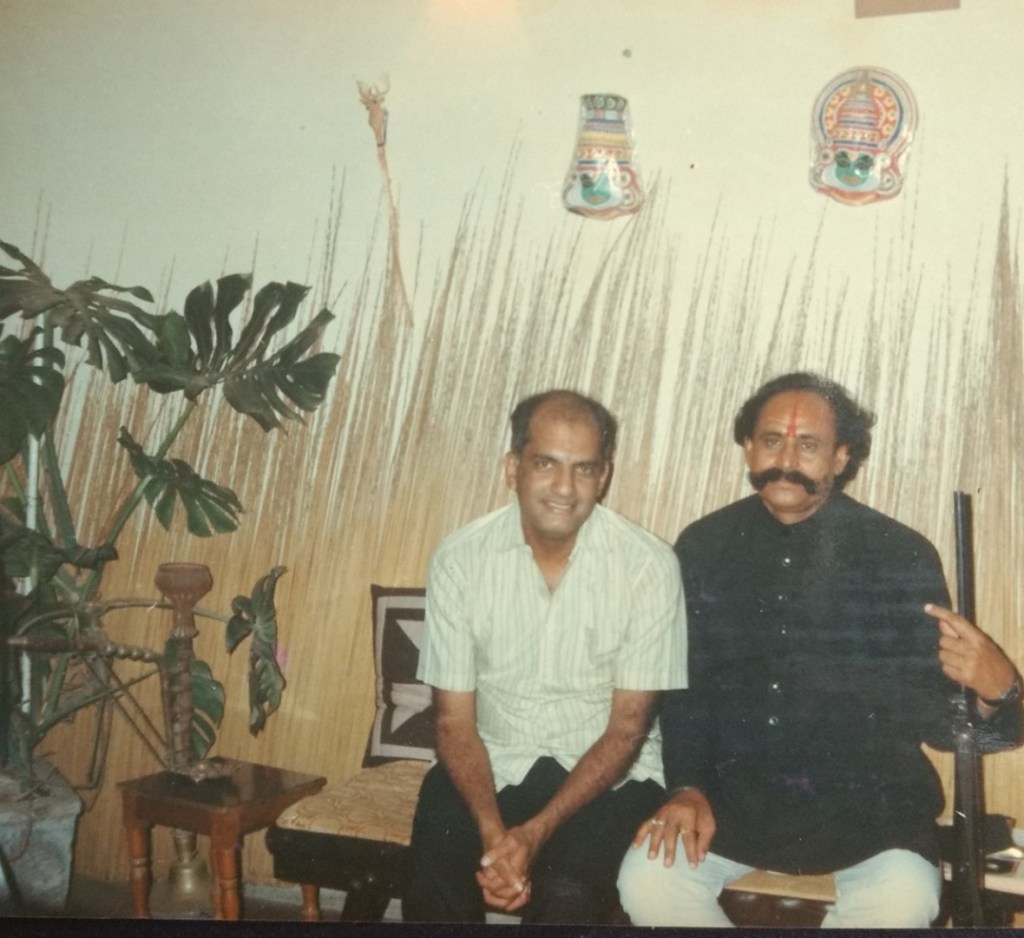

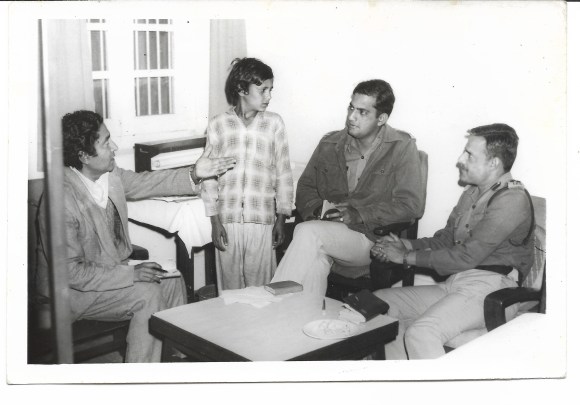

Ratnottama Sengupta, introduces the late Vijay Raman and converses with Veena Raman, the widow of this IPS[1] officer, about his book, Did I Really Do All This: Memoirs of a Gentleman Cop Who Dared to be Different. The memoir was recently launched by Sengupta and brought out posthumously by Rupa Publications.

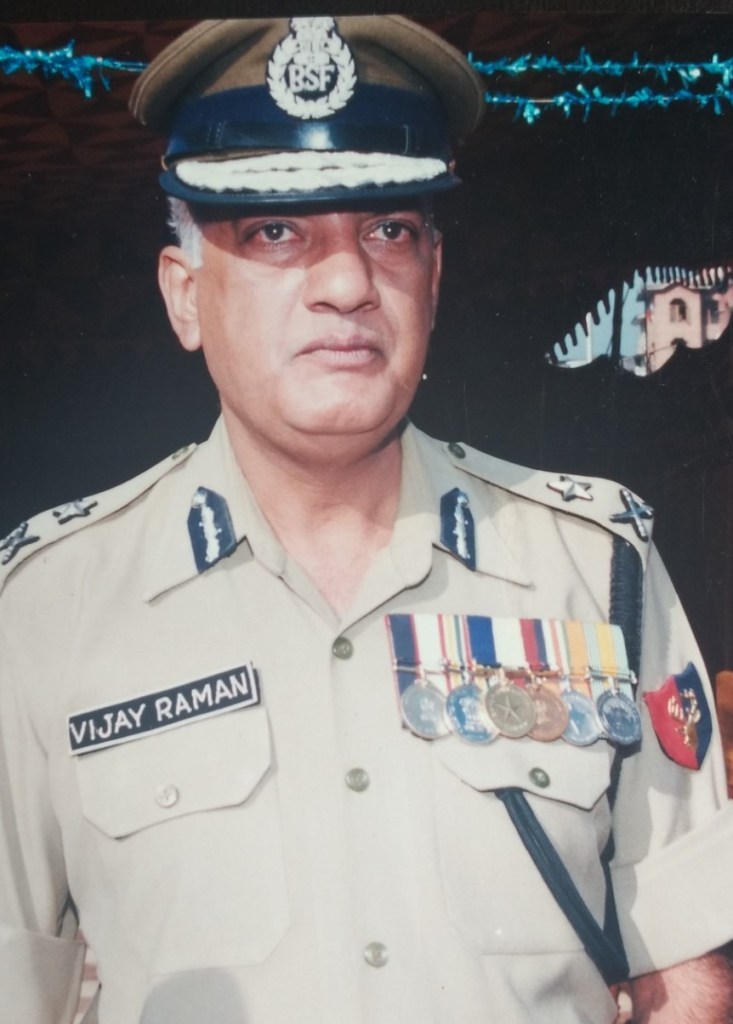

Vijay Raman’s success as a police officer was not merely a personal triumph. The career of this IPS officer traced the changes in the history of India’s security measures. India’s police organisation in 1947 — the Intelligence Bureau, Assam Rifles and CRPF[2] — were legacies from the British Raj. The 1962 Indo-China War led to the creation of the ITBP[3]; the 1965 war with Pakistan formed the BSF[4]. Investments in the Public Sector Undertakings led to the establishment of CISF[5]. Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1985 led to crafting of SPG[6]. The sabotaged crash of Air India’s Kanishka[7] and the Operation Blue Star prompted the formation of NSG[8], and the 2008 terror attack on Mumbai was followed by NIA[9]. Vijay Raman’s life was intertwined with these organisations. He was also responsible for bringing in a number of terrorists and dacoits, including the notorious women dacoit, Phoolan Devi[10] (1963-2001)…He died last year.

In this conversation, Veena Raman[11] reflects on his life and his memoir, Did I Really Do All This: Memoirs of a Gentleman Cop Who Dared to be Different.

Veena this book is a tribute to a police officer who brought honour to his uniform. Having met Vijay Raman I know how wonderful a person he was – deeply loved by not only his family and friends but also many VIPs he interacted with in his professional life. Is this your way of mourning his sudden demise?

When Vijay passed away we — my son Vikram, daughter-in-law Divya, grandson Shaurya and I — were devastated. The cruel illness was swift and relentless: within months he grew weaker before our eyes, and before we were ready to accept the loss. We had no choice but to face it. While we tried to console each other Vikram said, “Mamma we should be grateful that we had him for all these years. After all, Papa was that proverbial cat with nine lives!”

Really?

Absolutely. And why nine? I can give you 19 instances in our years together when his life was in danger and he miraculously escaped.

I am all ears Veena!

At the very outset, in November 1978, when Vijay was in his first posting as assistant superintendent of police (ASP) in Dabra, Madhya Pradesh, a country-made bomb was flung at his jeep by agitating students in Gwalior. It fell and exploded nearby. Fortunately, no one was harmed.

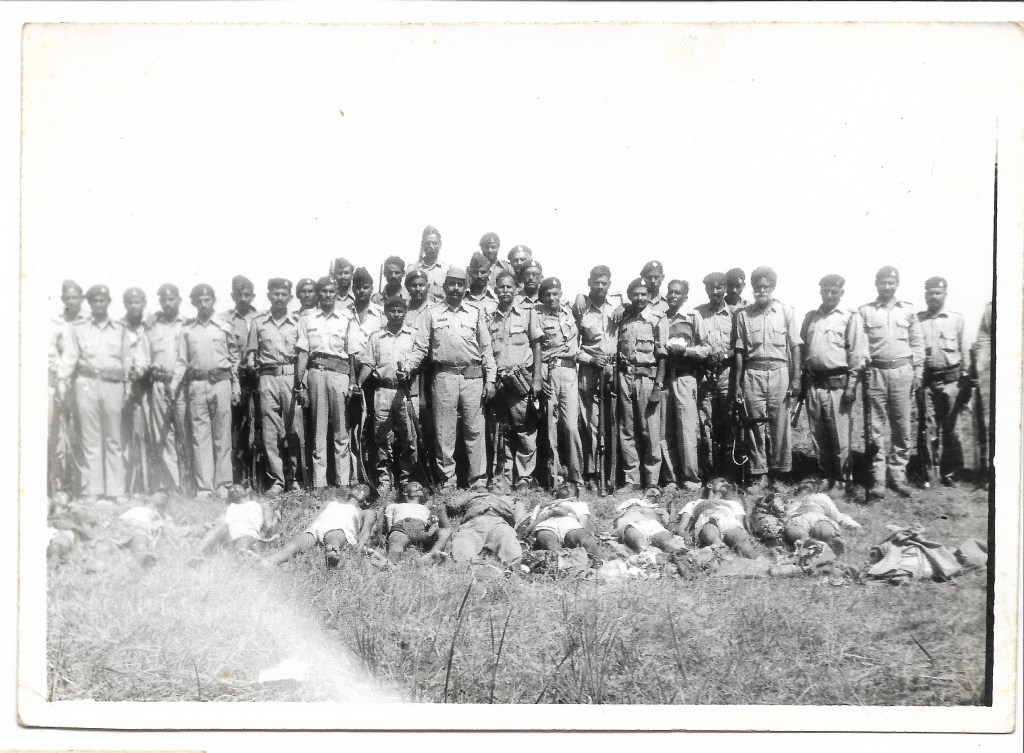

In 1981, based as he was in the Chambal, notorious for dacoits who stalked the nooks and crannies of the ravines, my illustrious husband had already faced dacoit encounters. The most dramatic of these took place in October, when he led the team that wiped out Paan Singh Tomar who, with his gang, had terrorised the region for years. As he describes in the book, bullets had rained on the encounter team from all sides, caught in the crossfire between the dacoits and the police.

He was superintendent of police (SP), Special Branch in Bhopal when the world’s worst industrial disaster took place. On the night of 3 December 1984, more than 40 tons of methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas leaked from the Union Carbide pesticide plant. At exactly that time Vijay was driving to the railway station. “Why inconvenience the driver to stay up late when I want to receive my parents myself?” he had argued.

Within minutes the gas had created havoc. He was shocked to see hundreds killed and untold hundreds maimed. Somehow he and his parents, so close to the scene of destruction, were spared.

In 1998, as inspector-general of police (IGP) Security, Jammu and Kashmir, while Vijay was in Srinagar, a bomb blast took place on the route during the hour he routinely travelled to office. He was saved that day because his driver had taken an alternative route!

In 2000, as IG-Border Security Force (BSF), Jammu, Vijay was responsible for erecting a much-needed part of the fence between Pakistan and India under highly adverse conditions. Enemy bullets rained down from across the border throughout the operation. That forced him to take some daring and potentially controversial decisions. How very relieved and thankful we were when he came home safe!

Vijay was appointed IG, BSF, Kashmir, in 2003 with the secret mandate to get Ghazi Baba, the mastermind of the 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament. Along with an informer, he had gone on an undercover exploration of the site where the encounter eventually took place. Most unexpectedly the informer pointed out the man himself! Vijay instinctively tried to open the car door and rush out to apprehend the terrorist. The informer roughly pulled him back and screamed to the driver to step on the accelerator and escape immediately. Later the informer explained that Ghazi Baba never left his lair unless he was strapped with explosives, and an attack would have spelled explosions that would have been the end of everyone in the vicinity.

Did he ever face a situation that he regretted?

One of the most dangerous situations Vijay ever faced in his risk-fraught career was as Special Director General (DG), Anti-Naxal Operations of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). In April of 2010, many of his men were massacred in Dantewada by Naxalites. The loss weighed so heavily on him that his health declined: he neglected his meals and even forgot to take his medicines. He had moved from the headquarters in Chhattisgarh to Kolkata; Vikram and I were in Delhi. We understood the intensity of what he was going through only later, when he suffered a stroke.

Did your angst-ridden years end with his retirement?

Not really. For, four years after he retired, in 2015, Vijay was handpicked to be a member of a special investigation team (SIT) to investigate the Vyapam (Vyavasayik Pariksha Mandal[12]) examination scam. This was a challenging assignment because the entrance examination admission and recruitment had been going on since the 1990s and had come to light only in 2013.

Did he do anything that was not challenging? What got him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records?

Vijay came close to death even in the personal adventure he undertook with a friend. Together they circumnavigated the globe in an Indian-made car in the last 39 days of 1992. Don’t forget, that was an era when Indian manufacturing was just coming of age. Though this tremendous feat earned him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records, he was exposed to danger of a different kind. For 39 days, they drove at very high speeds, in different countries, different terrains, and different political climates. Let alone sleep on a bed, many a night they could not even catch 40 winks. And still they had only one accident! Yes, it left him badly injured, but he found the strength to complete the challenge and beat the record.

Doesn’t every policeman court danger — even death — in the course of duty? What made him stand apart from other men with stripes?

True, every policeman faces bullets in the course of duty. And Vijay, throughout his career, was inviting them, to see what they could do to him. His faith in the divine, in his own destiny, made him fearless. How very fortunate we were that, time and again, they were deflected.

Another thing that made him stand out was his sheer artlessness. In a field of work steeped in the dregs of humanity, he stood unwavering by the principles of human rights and democracy. Again, fortunately, he came out unscathed, retaining faith in humanity all through life.

This dream run surely merited documenting. And Vijay had a flair for writing. So why did he not pick up the pen until the last hours of his life?

It was indeed a dream run. And that was precisely why I urged Vijay for years to write a book. Yes, many people have achievements, but his narrative was different. Winning without challenges is victory, but winning after overcoming challenges is history!

I remember that, when you visited us in Pune in 2019, you had said that the range and scope of what he had done, deserved to be recorded. I myself maintained that the consistently straightforward way in which he had done it, had to be recorded for posterity. But whenever this was suggested Vijay would say, “Who would be interested in such a book!”

None of us agreed with him. We read books by many other police officers which made it clear that Vijay’s experiences were unique. While the others excelled in certain areas of policing, Vijay’s was a whole range of spectacular achievement!

He may be the only police officer in the country who has dealt with all the aspects of policing — and been successful at each. He was at the forefront of dealing with the changing nature of crime in the country and also at the epicentre of varied policing challenges.

Doesn’t he write about how his actions led to change in tackling crime and criminals?

Yes, his successes invariably led to major changes in the law-n-order situation in the region. In Bhind, removing the Paan Singh[13] gang led to the surrender of a large number of dacoits who previously considered themselves invincible. This list includes the most notorious Malkan Singh[14] and the celebrated Phoolan Devi.

Similarly, when Vijay initiated the Indo-Pak border fencing, it was a major deterrent because most of the infiltration was from Jammu and there was a marked decline once the fence came up. Ghazi Baba too was seen as invincible, so the encounter destroyed a formidable opponent and also sent a clear message to enemies across the border.

Vijay’s success was not merely personal triumph. His career as an IPS officer traces the changes in the history of India’s security measures, right?

Indeed, his life and career were intertwined with an entire spectrum of events that enhanced the security of Indians. But let me point out that his daily life also contained an extraordinary range of experiences. He grew up in a village in Kerala, and later lived in villages among the most primitive of peoples in other Indian states. But he also lived in the cities, a privileged urban Indian. He had travelled in bullock carts on rutted roads and often walked 30 km in the course of an ordinary day through ravines. And he had also jetted across the world with the prime ministers he protected.

Vijay exemplified the essential truth of India being one, from Kashmir to Kerala!

Without a spec of doubt Vijay was that quintessential Indian who was intimately connected in different ways to the length and breadth of India. He grew up in Kerala, the deepest south, and spent some of the most significant years of his career in Jammu and Kashmir, the farthest north. His higher education took place in Gujarat; when he retired, we came to live in Pune.

The western part of India was his beloved home as an impressionable youngster, and then again in his final years. There were formative experiences in the east when, as a probationer in the Police Academy, he was taken to explore and understand India’s verdant Northeast. And he was in Calcutta for induction training at the ordnance factory, and later during his stint as Special Director General, Anti-Naxal Operations of the CRPF.

With these influences of north, south, east and west, it was only fitting that Vijay should be allotted the Madhya Pradesh cadre, at the very heart of India.

And he met his darling wife – then a hockey champion – in Nagpur! How did you meet? And how did you sustain your enchantment when the miles kept you in different corners of the land?

Vijay was an excellent writer. Of late I’ve been reading his letters to me over the years, from before we were married as well as during the tenures of separation induced by our work and careers. I can only marvel at his intellectual ability. Even at a very young age, he articulated his thoughts and feelings beautifully, and the letters reflect his tendency to introspect often, and be constantly self-critical.

I see a proud wife sitting before me.

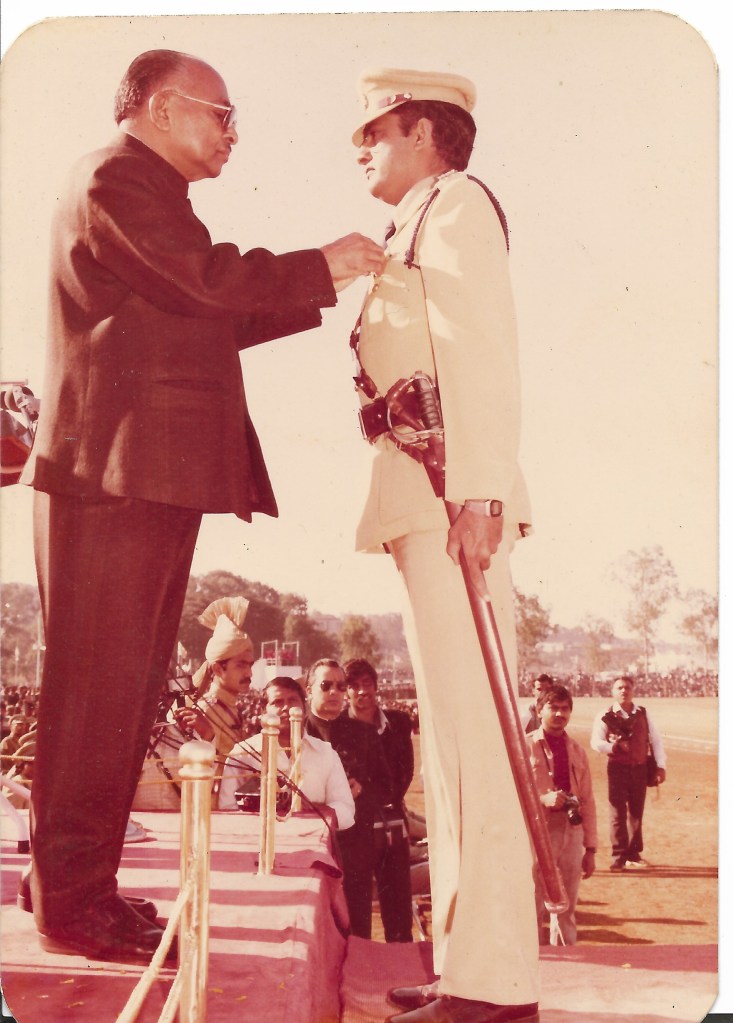

I have always been extremely proud to be the wife of such an exceptional human being. But Vijay disliked being praised. At the peak of achievement, when his heroic deeds were earning him medals and he was surrounded by people singing his praises to the sky, when he was achieving success after success, he tried to ignore it all. Specifically he would tell me, “Please Veena, you don’t praise me. It’s all right that so many people are praising me. But if you start doing it, it’ll go to my head.”

Stupidly, I took him at his word. Of course, I boasted to others that the outstanding police officer was also the best husband, and the best father, ever. Even in the 1970s, when so few women had careers, he supported my ambitions. He knew he was marrying a woman who had her own dreams, who wanted to see the world. And yes, he knew that I had not learnt to cook!

I admired many other things about him. His commitment to perfection no matter how inconsequential the task. His commitment to service, to justice, to humanity. His love for reading. His wry sense of humour. His care for his parents and members of both our families. The deep respect he drew from whosoever knew him well — his family, his colleagues, his subordinates, his superiors, and even many criminals he came in contact with in the course of his duties.

But because he stopped me from praising him, I could never convey to him in words how much I admired him. It was only when he grew weaker that we worked fast and furious to get down on paper all that he was telling us. And as we approached the final pages of this book he said to me, with some surprise and wonder, “Veena, did I really do all this?”

So this book is Vijay’s story in his words. When he became too weak to speak, and when we lost him, my memories continued to pour in and I took the liberty to fill a few gaps.

May his legacy live on!

The A B C of Vijay Raman

Adventure: Awarded citation in Guinness Book of World Records and Limca Book of Records for his around the world tour in an Indian Contessa car in 39 days 7 hrs 55 minutes

Brains: Gold Medals in Law

Courage: Presidents Police Medal for Gallantry

Experience: Over 34 years of rich experience in General Administration, Policing, handled PM Security, CM Security, anti-dacoity operation in Chambal, anti- terrorist operations in Jammu & Kashmir , anti-Naxalite operation, Investigated Vyapam Scam.

Awards

• Presidents Police Medal for Gallantry.

• Presidents Police Medal for Distinguished Service

• Presidents Police Medal for Meritorious Service.

• Gold medals in Law

Click here to read an excerpt from I Really Do All This: Memoirs of a Gentleman Cop Who Dared to be Different

[1] Indian Police Service

[2] Central Reserve Police Force

[3] Indo Tibetan Border Police

[4] Border Security Force

[5] Central Industrial Security Force

[6] Special Protection Group

[7] 1985 crash of AI 182 to London

[8] National Security Guards

[9] National Investigation Agency

[10] Phoolan Devi (1963-2001) was married at the age of eleven and sexually assaulted before she became a dacoit. She was jailed for eleven years and then joined politics till she was assassinated.

[11] Veena Raman retired as General Manager Marketing, Madhya Pradesh Tourism, after serving for 29 years. After retirement, she joined two NGO organisations, University Women’s Association Pune and Pune Women’s Council working towards empowerment of women. She was part of the national hockey team of India in 1975.

[12] Madhya Pradesh Professional Examination Board

[13] Paan Singh Tomar (1932-1981) was an Indian athlete and soldier who became a dacoit due to family feud.

[14] Malkan Singh (born 1943) is a former dacoit who has turned to politics

.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International