Book Review by Meenakshi Malhotra

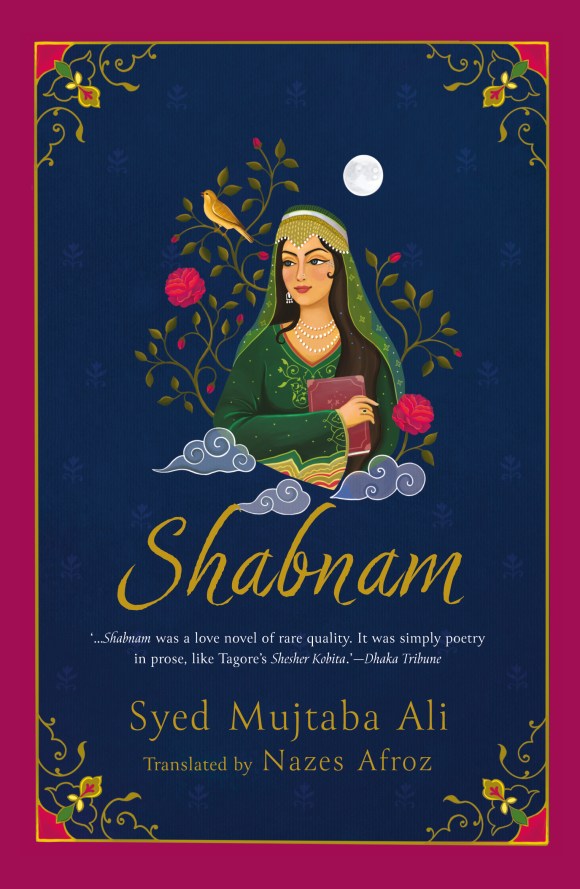

Title: Shabnam

Author: Syed Mujtaba Ali

Translator from Bengali: Nazes Afroz

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Shabnam (1960) by Syed Mujtaba Ali is a love story that is set in the third decade of the 20th century. ‘Shabnam’ in Persian means a ‘dewdrop’. The polyglot scholar Mujtaba Ali’s love story becomes a vehicle for articulating the profundities of life which extends beyond the plot and the telling just like that of his teacher, Rabindranath Tagore. To quote the words of another reviewer: “His novel can be compared to a dewdrop which assumes rainbow hues during sunrise as it encompasses not only the passionate cross-cultural romance of Shabnam and the young Bengali lecturer, Majnun, but also shades of humanity, love, compassion set against the uncertainties generated by ruthless political upheavals.” Sweeping in scope, set against the backdrop of the Afghan Civil War (1928-29) and beyond, the novel narrates an epic love story. That this has recently been translated by a former BBC editor stationed in Afghanistan, Nazes Afroz, and published for a wider readership, emphasises its relevance in the current context, where regressive curtailment of human rights and liberties are evident on a daily basis.

Shabnam is a young, upper class and educated Afghan woman, fluent in French and Persian. As we learn in the course of the narrative, she is daring and apparently fearless. She is proud of her Turkish heritage as she invokes it while introducing herself: “You know I’m a Turkish woman. Even Badshah Amanullah has Turkish blood. Amanullah’s father, the martyred Habibullah, realised how much power a Turkish woman—his wife, Amanullah’s mother—held. She checkmated him with her tricks. Amanullah wasn’t even supposed to be the king, but he became one because of his mother.” Given the current context, with its attack on womens’ freedom, it is perhaps difficult to imagine that a woman like Shabnam or anyone with a similar persona or voice could be found at all. She seems at times to inhabit the rarefied realms of her author’s imagination, beyond the earthly realm.

Shabnam’s knowledge of history and the world is extensive. She actively chooses and decides about her surroundings and her own life, which is more than what many women can do in today’s Afghanistan. Characters like Shabnam are also the result of the varied travels of the author Mujitaba Ali, who traveled and taught in five countries. On the power wielded by women, Shabnam offers a rejoinder to her lover/narrator: “In your own country, did Noor Jahan not control Jahangir? Mumtaz—so many others. How much knowledge do people have of the power of Turkish women inside a harem?”

The novel has a tripartite structure. In the first part, is the dramatic meeting of the narrator, Majnun, with the striking and unconventional Shabnam at a ball given by Amanullah Khan, the sovereign of Afghanistan from 1919 to 1929. The novel’s narrative is dialogic in nature and the introduction and subsequent exchanges of the protagonists are peppered with wit and poetry. The first part concludes with the two of them acknowledging their love for each other.

In the second part of this novel,we witness more developments in their relationship. Shabnam assumes an agential role and makes a decision to marry Majnun secretly with only their attendants looking on. And then later, this decision receives a legitimate sanction since a wedding is organised for them by her father, who does not know they are already married. Despite the xenophobic approach in those times of many Afghans (and other South Asian communities) against marrying their daughters to foreigners, her family decides to marry Shabnam to Majnun as they wanted her out of conflict-ridden Afghanistan and in a safer zone. Her father hopes she will go off to India with her husband. This seems unexpectedly progressive in the Afghanistan of almost a century ago. But instead, in the third part, she is abducted by the marauding hordes while her beloved attempts to organise their return from Afghanistan.

The last part continues with Majnun’s quest for his beloved. His endeavour leads him to travel, hallucinate and drives him almost insane, reminiscent of the Majnun of Laila-Majnun fame, a doomed union that resonates in and forms a motif in the narrator/lover’s repeated conversations with Shabnam. At the end of the novel, Majnun ascends the physical realm of love. He says: “Now after losing all my senses, I turn into a single being free of all impurities. This being is beyond all senses—yet all the senses converge there… There is Shabnam, there is Shabnam, there is Shabnam.”

The novel concludes with the realisation that “there is no end” (tamam na shud). This feeling seems to echo the idea of “na hanyate hanyamane sarire”(“It does not die”) in Sanskrit signifying that love is eternal, even beyond the material realm. Both the luminosity and fragility of love is represented in the novel.

Mujtaba Ali’s wide and varied experience is in evidence at several points in the novel, as is his wit and satiric sense, some of which filters through to his created characters. This can be experienced in the dialogues and descriptions even in its translated form. In order to conceal her identity from the marching and rustic hordes, Shabnam comes to visit her beloved in a burqa. She argues that it is not a symbol of oppression but a self-chosen disguise: “Because I can go about in it without any trouble. The ignorant Europeans think it was an imposition by men to keep women hidden. But it was an invention by women—for their own benefit. I sometimes wear it as the men in this land still haven’t learned how to look at women. How much can I hide behind the net in the hat?”

A valuable addition to the rich corpus of travel writing in Bangla Literature, the book remained unknown to the world outside Bengal despite its excellence as there were no translations. In 2015, Afroz had translated and published this book as In a Land Far from Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan. It was subsequently shortlisted for the Crossword Book Award. That translations can provide a bridge across cultures is eminently clear from this work, which gives us a tantalising glimpse of a culture beyond our own and encourages us, the readers, to recognise that true love transcends borders or boundaries and that the language of true love is the same everywhere.

The novel’s title, Shabnam, is a natural choice, as the intelligent, courageous and beautiful Shabnam is the emotional centre of the novel. To describe her ineffable charm, we could draw upon Mujtaba’s teacher’s words, in Gitanjali (Song Offerings by Tagore):

She who ever had remained in the

depth of my being, in the twilight of

gleams and of glimpses…

… Words have wooed yet failed to win

her; persuasion has stretched to her its

eager arms in vain.

Song 66, Gitanjali by Tagore

Majnun, the narrator lover is left, in Tagore’s words: “gazing on the faraway gloom of the sky, and my heart wanders wailing with the restless wind.” Romance by its very nature, is fleeting and transient and romantic love in its literary avatars/depictions acquires a bitter-sweetness when its founded on loss and longing. So it is with Shabnam.

.

Dr Meenakshi Malhotra is an Associate Professor of English Literature at Hansraj College, University of Delhi, and has been involved in teaching and curriculum development in several universities. She has edited two books on Women and Lifewriting, Representing the Self and Claiming the I, in addition to numerous published articles on gender, literature and feminist theory. Her most recent publication is The Gendered Body: Negotiation, Resistance, Struggle.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International