A stock taking of women in Bengali cinema – as protagonists, actors and directors – by Ratnottama Sengupta

“Mother, allow me to go and get a slave for you,” this conventional line may have been uttered by the husband essayed by Anil Chatterjee in Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963), as he set out to marry Aarati alias Madhabi Mukherjee. Women of those years had no problem accepting such husbands as their Lord and Master. But the lead actress of Ray’s film evinced determination of a different order. That’s why even today, 52 years after its release, Mahanagar remains so contemporary.

Time was when women in Indian — rather than just Bengali — films were typecast as mother, sister or beloved of a male character. The mother would sacrifice her creature comforts, her career, her every happiness for her son — but if she cared for her brother, she would be rebuked (Mejdidi, Second Sister, 1950; 2003). If she offered shelter to her orphaned sister, she would have to ‘repay’ her in-laws for the favour by making her work overtime (Streer Patra, The Wife’s Letter, 1972). It was ‘her’ responsibility to stay ‘pure’. If she were ‘tainted’, she had no option but to embrace death. The long-suffering Indian woman has left way behind her ‘helpless’ (abala) definition: No Nirbhaya needs to die of shame if she’s the victim of rape. The silver screen is reflecting this transformation. She’s no goddess (devi) nor a slave (dasi) — she’s proud to be what she is: a woman (nari).

But a woman is always more vulnerable, more fragile compared to a man. Reason? Could be biological, economic, social structure, or her lack of confidence born of mental malnutrition. Perhaps that is why women have provided material for intense human drama. At times she is Lady Macbeth or Lady Chatterley, at other times she is Mrinal (of Streer Patra), or Ashapurna Devi’s Subarnalata (1981). Besides, Bengal worships Goddess Durga — in this state, women are simultaneously Saraswati, the goddess of learning; Lakshmi, the deity of prosperity; and Kali, the icon of destruction. That may be why, from the beginning of Bengali cinema, lead personalities have enjoyed multidimensional projection. Sometimes a mere ‘actress’ becomes a mouthpiece for a socially sensitive and relevant issue, sometimes she is the face of psychological conflict, sometimes she is a philosopher, preacher.

Un-Covered

There are many different ways to approach the projection of women in Bengali films. Literature has always been the first to convey their self-sufficiency — be it on this soil or elsewhere. Gems mined from Bengali literature provided the raw material for pioneers like Naresh Mitra (1888-1968), Pramathesh Barua (1903-1951), Debaki Kumar Bose (1898-1971), Nitin Bose (1897-1986), Bimal Roy (1909-1966) — giving us landmarks such as Jogajog (Connections, 1943; 2015), Durgesh Nandini (Queen of the Fortress, 1956), Bishabriksha (The Poison Tree, 1922; 1983), Debi Chaudhurani (1974; upcoming 2025), Biraj Bou (Biraj, the Wife, 1972), Pather Dabi (The Right of Way, 1977), Udayer Pathey (Towards the Dawn, 1943). However, the minute we utter the two words — ‘women’ and ‘literature’ — in one breath, we think Pratham Pratishruti (The Early Promise, 1971) and Subarnalata (1981). Together they are a flawless portrayal of social transformation and women’s emancipation.

Dinen Gupta had filmed Pratham Pratishruti even before Ashapurna Devi had won the Jnanpith Award. Its protagonist Satyawati kept at it but did not succeed in altering the social dynamics of Women’s Education. Her daughter Subarnalata is married off in her childhood, into an urban family with rustic mindset. Alone, unsupported she fights the male chauvinists (and this includes the women too!) who were unfamiliar with the word ‘self-identity’; whose only understanding of women’s honour, sanman, comprised of ghomta-sindoor, the veil and the vermilion. Despite her efforts, how often do we hear of a Bakul (Subarnalata’s daughter) who rides a bike to drop off her elder brother to his college?

Streer Patra devolves around ‘Mejo Bou’ Mrinal (Madhabi Mukherjee). She has the freedom to offer shelter to her sister-in-law’s sibling but not to love, educate, and honour her. When the sister, pushed into marriage with a mentally deranged person, commits suicide, Mrinal leaves home in protest. But her protest is not a sentimental reaction, so she does not end her life in the ocean. Nor does she sign off her letter as ‘Mejo Bou’ — the Second Bride of the joint family – which was till then her only identity. She is now ‘Charantalashray Chinna Mrinal’, one who has lost the protection of her husband’s feet.

*

Long before Purnendu Pattrea, Bimal Roy had set an example in ‘deconstructing’ the well-entrenched structure of male domination even in wealthy families. When it came in 1943, Udayer Pathey had broken several norms: Jyotirmoy Roy was an unknown writer, Binata Roy was not a conventional beauty. As the daughter of an industrialist — read, a 20th century princess — she takes up the fight for labourer’s rights and leaves the shelter of her father and brother to make a home with a ‘hired’ writer. She was emboldened by her predecessors like Kanan Devi who became a star in Mukti (Liberation,1937).

Rebellion need not necessarily be a battle — won or lost — as Sujata (1974) showed. Litterateur Subodh Ghosh, who created the character, imagined her as a sweet, caring persona, who is alert to every little need of her foster family. But, despite all her care and love, she doesn’t become ‘a daughter’ to the parents she dotes on. Her fault? She is born of ‘untouchable’ genes. An even bigger fault? She is loved by the man whom the foster parents want to see as the husband of their biological daughter. Film director and writer, Pinaki Mukherjee, fired away with this double-barrel gun although he knew it was impossible to overshadow Nutan’s performance in Bimal Roy’s Sujata (1959).

Director is Special

Follow the director and you land at the door of Satyajit Ray. If his filmography opens with Pather Panchali (Song of the Road, 1955), his depiction of the mother, Sarbajaya, opens the pantheon to women who are found in any middle-class home. Women who are not dressed like the shiny stars of saas-bahu shows but cringe nevertheless when it comes to feeding their aged mother-in-law. Women who have no big dreams for their children but to protect them from any hint of slander by the neighbours.

Half a century later Mahanagar remains a head-turner. Its protagonist Aarati is a working woman whose pay-cheque keeps the kitchen fire going. But this does not place a halo around her head. Instead, society crinkles its brow at her. Still, she does not shy from protesting a wrong done to her colleague. Still, she does not think twice before turning in her resignation. She is not scared of the dark days ahead — because she has light within. She has confidence in her own entity.

Prior to that Ray had etched with care the homemaker Charulata (1964). She too is a housewife but from another world, in terms of both time and social status. The educated wife of a wealthy intellectual — an editor who has no time to chat with his wife or hear her out — she sews, she writes, she is published in journals… If the devotion of such a woman finds an anchor in her brother-in-law, what would the world say of the ‘homebreaker’?

Charu’s husband Bhupati must shoulder the blame for wrecking the marriage, but Nikhilesh (Victor Banerjee) of Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1984)? The zamindar stood by his wife when Bimala (Swatilekha Sengupta) stepped out of the inner courtyard and wedded herself to the nationalist fervour of Sandip (Soumitra Chatterjee). Perhaps that is why, when she realises that Sandip loves himself far more than his motherland, the disillusioned wife returns to her original ‘guru’ — her husband. There is no shame nor despondency of defeat in this, for this is not regressive, it is merely a ‘course correction’.

*

Ritwik Ghatak, a contemporary of Ray, envisaged women as the Lakshmi-Saraswati-Kali of a partitioned Bengal.

Nita (actress Supriya Devi) in Meghe Dhaaka Tara (The Cloud Capped Star, 1960) earns to feed her parents, marry off her sister, build her brother as a vocalist… But who cared for her love? Her dreams? Her sheer desire to live? At the other end of the spectrum is Sita (Madhabi Mukherjee in Subarnarekha, 1965). She had held her fatherly elder brother’s hand when the child had to seek refuge across the barbed wires. She sacrificed that secure shelter (of her brother) to her love. When that love proved ephemeral, she sought survival in the world’s oldest profession. When that profession placed her face to face with a fallen angel — her brother — she turned into Kali, the destroyer.

Mrinal Sen’s Baishe Shravan (The 22nd of Shravan, 1960) was an essay in marital discord in the disjointed times of war. But times change, and with that going out to work becomes routine for women in Bengal. No one looks askance — so long as she returns home by nightfall. For, that is one routine that hasn’t changed: even today, exceptions to it are meant only for men. Even today, if a Nirbhaya is gang-raped, many react by asking, “Why was she out so late?!” So, when the breadwinner daughter in Ekdin Pratidin (And Quiet Rolls the Dawn, 1979) does not return home, she is branded a siren even before she is given a hearing.

Tapan Sinha has repeatedly pointed to women’s vulnerability. His Nirjan Saikate (The Desolate Beach, 1963) depicts the barren lives of single women, be they widows or spinsters. Jatugriha (The Inflammable Home, 1964) paints the pangs of legal separation and divorce. Adalat O Ekti Meye (The Law and a Lady, 1981) highlights the legal ‘molestation’ of a rape victim. Aapanjon (Dear Ones, 1968) bestowed a new kind of dignity on the uncared for senior widows. Wheel Chair (1994) became the symbol of struggle when a chairbound woman fights the injustice of a rape that leaves her incapacitated for life. Antardhan (Missing,1992) opened our eyes to the base trade in human flesh. And the Daughters of This Century (Satabdir Kanya, 2001)? Better not talk of them, Sinha might say, for like Kadambini of Jibito O Mrito (Alive and Dead), they have to die in order to prove they were living!

Aparna Sen, as a popular actress, did characterise some women of substance. She charmed us in Ekhane Pinjar (Caged Here,1971)as she slaved to provide her family a life of some worth. Much seen? Yes, it was a much seen reality in our midst. Shwet Patharer Thala (The Marble Plate, 1992), Prabhat Roy’s adaptation of Suchitra Bhattacharya, showed that despite the changed times, a widow’s is still a solitary struggle. A single shot in Paramitar Ekdin (House of Memories, 2000), under her own direction, makes her unforgettable. As the mother-in-law who loves fish, she’s chewing on a fishbone with deep satisfaction when she learns her husband is dead. “Over,” says the blank expression on her face, in her eyes, in her entire being, “no more fish.” That single look bespeaks sadness, disappointment, vacuum in the life of a Bengali widow. Why is it that a man does not stop having fish when his wife dies?

As a director Aparna uses the same fish, to establish a progressive mindset. When her daughter-in-law, Paromita (actress Rituparna), takes her to a restaurant and treats her to a fish fry, we viewers are delighted. She herself has suffered, so the daughter-in-law understands the mom-in-law’s suffering. Not for her the ‘revenge’ story of family dramas.

At the very outset Aparna Sen had given a fair indication of the road ahead. Elderly and lonely, Ms Stoneham in 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981) is poised against her ebullient, self-centred, even ruthless student Debasri Roy. The two worlds of seniors and youth clash again in Goynar Baksho.(The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die, 2013). But this child widow, Pishima (the aunt), extracts every inch out of life. Even after death she demands her pound of flesh: she smokes, she bikes, she zealously guards her dowry, streedhan. She even encourages extramarital love! But, perhaps, Aparna Sen’s boldest statement is Paroma (The Ultimate Woman, 1985). Should a woman bury her sexuality simply because marriage has turned her into someone’s aunt or a sister-in-law? “No” — comes the unflinching reply.

*

Women are deprived, exploited. They protest, they rebel. They stride ahead alone and draft a path for others to follow. Their confidence gets a boost, they enlighten hide-bound males, transform mindsets. This is how we see women in Rituparno Ghosh’s oeuvre. He drew our attention towards several issues, but the empathy in his tenor led us beyond the immediate pre-occupation and endowed his scripts with such universality that free-thinking men, too, had no issues with them.

In Unishe April (Nineteenth April, 1994), the national honour of a Padmashri for Sarojini angers her daughter. Because? She chose to be a danseuse rather than a homemaker, and sent her daughter to a hostel so that she could dance on. Dahan (Crossfire,1997)sees Ramita molested by strangers on the street, but the man in her bedroom? What about him? Surely you won’t construe a ‘husband’s conjugal right’ as ‘marital rape’?! On the other hand, Jhinuk has to pay a price as the witness. She is put in the dock by the law of the land, and dropped by her boyfriend. Banalata in the Bariwali (The Landlady, 2000) has aged but not married. Her dreams of a family are somewhat fulfilled when a film unit comes to shoot in her ancestral mansion. She drapes a red-bordered sari and dons sindoor in her hair too, for a single shot. But that’s mere acting! The director’s praise and love for her too was acting! Kiron Kher as Banalata realises this when she sits in the darkened theatre, and finds the scene has been clipped out of the film. How many times will you be shortchanged, lady, emotionally too?

In Antarmahal (The Inner Chamber, 2005), Zamindar Jackie Shroff authorises a sacrificial yagna to ensure the continuity of his line with the birth of a son. And what is that sacrifice? In the presence of his first wife (Rupa Ganguly), he will copulate with his child bride (Soha Ali Khan). Night after night. Isn’t this mental as well as physical torture? So what! Isn’t he a zamindar and the husband too!

Dosar (Companion, 2006) sees the husband (Prosenjit Chatterjee), a corporate bigwig, returning with his secretary from a weekend retreat in his love nest. A massive accident leaves the woman dead, the husband bedridden, and the wife in a fix. Should she leave the helpless man, or restore life in the faithless marriage?

Even when All his Characters are Fictitious (Sab Charitra Kalponik, 2009), Rituparno Ghosh speaks an Eternal (Abahoman, 2009) truth: Women’s efforts to create an identity for themselves have been wrecked by men. Women have had to confront layer after layer of inhibition, prejudice, agony. But it is much worse to be a woman trapped in a male body, Rituparno showed in his last film, Chitrangada (The Crowning Wish,2012).

*

Bengali cinema was meant to be thus: modern, lively, brilliant. Viewers have said this time and again. After the release of Anuranan (Resonance,2006) Antaheen (The Endless Wait, 2009), Aparajita Tumi (You Undefeated, 2012) this was said for Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury. He has continuously shown that women ‘culture, nurture, explore’ life. Viewers had applauded when Bappaditya Bandopadhyay (1970-2019) handed over the right to ‘give away the daughter’ in marriage to the mother in Sampradan (The Offering, 2000). The director of films like Kaal (An Era, 2005) on human trafficking and Kantataar (Barbed Wire, 2005) on illegal migration, Bappaditya was ecstatic that in the present century, women are being recognised as ‘Researcher in Child Development and Interpersonal Relationships’. Women are morally superior, declares Srijit Mukherjee in Autograph (2010), when the jean-clad Srinanda (Nandana Sen) leaves her live-in partner (Indraneil Sengupta), for encashing the accidentally recorded confession of the star Arun Chatterji (Prosenjit) in an inebriated moment of weakness. Somnath Gupta projects a mofussil girl in Aadu (2011) who does not hesitate to write to the President of America to find out the whereabouts of her immigrant husband who went missing in Iraq after the outbreak of Gulf War 1. With Shunyo E Buke (Empty Canvas 2005), Kaushik Ganguly raises a question that still seeks an answer: Is a big-hearted woman less attractive than a big-chested one?

We have watched films that break stereotypes in startling ways. The protagonist of Atanu Ghosh’s Rupkatha Noy (Not a Fairy Tale, 2013) is a bride who flees home; an IT professional who admits to taking a life, and a gritty though little educated delivery girl at a petrol pump. Judhajit Sircar’s Khasi Katha (Saga of a Goat, 2013), centres around Salma, the motherless daughter raised in a convention bound Muslim family who works in a leather factory to feed her unemployed father and brother but fights to become a professional boxer!

The Actor is the Star

Irony, thy name is cinema. For, here, the deception of ‘acting’ must turn imagination into ‘real’. The personas are imagined, but they are rooted in our soil. Naturally, some characterisations remain with us forever. Thus, some actresses become the voice of women’s fight for emancipation. Suchitra, Supriya, Madhabi, Arundhuti, Aparna, Rituparna, Paoli –any of these actors in the central role promises a powerful document in the fight for women’s rights.

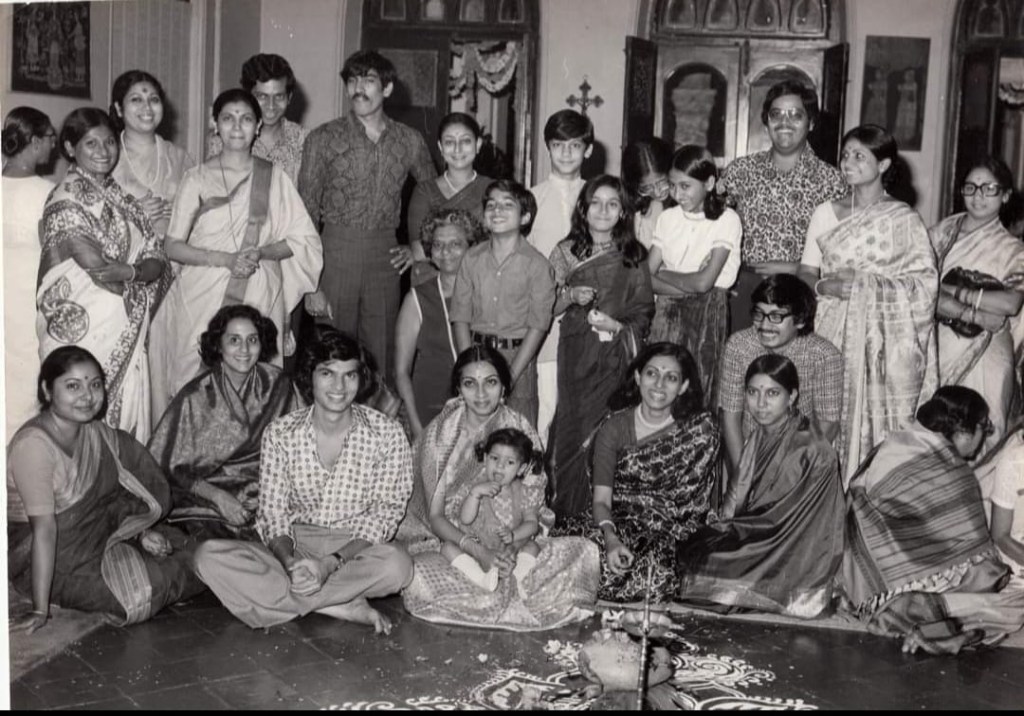

* It started even before Suchitra Sen (1931-2014), when Kanan Devi (1916-1002), Bharati Devi (1922-2011), Chhaya Devi (1914-2001) and Sabitri Chatterjee (1937) were playing at New Theatres, Chhayabani, Radha Films. We will return to Kanan Devi but meanwhile, let’s revisit Suchitra Sen. A married woman, mother of one, Mrs Sen became — and still remains — an icon, not only in the two Bengals but pan India. No gossiping with unit members, the detailing of her character, its costume, its co-actors kept her busy as long as she was in the studio. Understandably, her fame ignited jealousy and she was tarnished as temperamental, aloof, selfish…

Yes, unwilling to compromise in matters pertaining to her role, Mrs Sen would not spare even haloed producers like R D Bansal or Haridas Bhattacharya. But her glamorous dignity ensured a so-far unknown respect for actresses in Bengali filmdom, especially when her name was printed above Uttam Kumar’s, in posters pasted all over the town. Nylon sari, sunshades, short hair, sleeveless blouse — every expression of ‘modernity’ became Mrs Sen. She came to personify the middle-class Bengali woman who — married or not — could be a professional: journalist, nurse, doctor, singer, lawyer… On the other hand, the single-minded determination that characterised courtesan Pannabai and her hostel-educated daughter Suparna (Uttar Falguni, In Her Autumn, 1963), Rina Brown (Saptapadi/ Seven Steps, 1961), Archana (Saat Paake Bandha, Knotted by the Vows, 1961), and Radha (Deep Jwele Jai, To Light a Lamp, 1959) only reflected Mrs Sen’s own firmness of intent.

One Meghe Dhaka Tara alone was enough for Supriya Devi to shine through the annals of Bengali cinema. Add to that the appeal of Komal Gandhar (Soft Note on Sharp Scale, 1961). In many a film she is the beloved of matinee icon Uttam Kumar. What firmed her position was her boldness in accepting roles with negative shades. Be it Lal Pathar (The Red Stone,1964), Sanyasi Raja (The Monk Who Was a Monarch, 1975) or Mon Niye (All About Her Heart, 1969) — her presence gave a shine to both, the persona and the film.

* Sharmila Tagore went away to Bombay and Bollywood gobbled her, but she remains evergreen as Aparna of Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959), the newly wedded bride in Devi (Goddess, 1960), the journalist in Nayak (The Hero, 1966), the questioning eyes in Seemabaddha (Company Ltd, 1971) and the irrepressible, dark-complexioned tomboyish Ghetu of Chhaya Surja (Overshadowed, 1963). If Ray films cast her as the silent conscience speaking mainly through her eyes, Partha Pratim made her unforgettable in casting her in an opposite role.

* For a while, Tanuja ruled the Bengali heart from the theatre chain of Minar-Bijoli-Chhabighar. The frothy actress from Bombay became a hit with the superhit musical romance, Deya Neya (Give-n-Take, 1963). Uttam Kumar’s Antony Firingee (1967) immortalised her as Saudamini. And Nandini of Teen Bhubaner Pare (Beyond Three Worlds, 1969) broke new grounds in a society where it was customary for men to marry illiterate women, but unthinkable for an academic woman to marry an unlettered, alcoholic blue-collar worker. Husbands, after all, had to be superior, right? That’s why the highly educated princess of Ujjain during the Gupta period (3-4 CE) was ‘taught a lesson’ by being fooled into marriage with the worthless Kalidas, who eventually rose to be the peerless poet of Sanskrit classics like Abhijnana Shakuntalam and Meghdoot!

* In recent decades, Debasree Roy bagged the Golden Lotus through significant films like 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981), Unishe April (19the April, 1994), Asukh (Ailing, 1999), Ek Je Achhe Kanya (There’s This Girl, 2001), Dekha (Vision, 2001), and Nati Binodini (The Actress, 1994). Her contemporary, Rupa Ganguly scored nationally as Draupadi in the television serial Mahabharat (1988). The riveting beauty of the epic had ruled the five Pandava brothers who took on the male order of the Kauravas — the clan that de-robed her — even as their patriarchal head remained a silent spectator. Rupa endowed the persona with a rare dignity that came to the fore again in Antarmahal (The Inner Chamber, 2004) saving it from becoming voyeuristic. Instead, she evoked pathos and a certain sadness in us when her husband proceeded to copulate with a younger wife in front of her eyes. Again she won our applause and institutionalised laurels in Abosheshey, (Finally, 2011) as the mother whose separated son, raised in America, comes to know her heartbreaking love for her child after her death. And in Sekhar Das’s Nayanchampar Din Ratri (The Tale of Nayanchampa, 2019) she breathes life into the marginalised character who epitomises the multitudes that travel from the suburbs to serve as maids in urban homes.

Rituparna Sengupta, the first of the divas from Bengal today, wears the mantle of Kanan Devi. Like the icon, she excelled in acting, bagged the Golden Lotus for her performances, and then started a production house, Bhavna Aaj O Kaal. This has enabled her to get a veteran like Tarun Majumdar to direct her in Aalo, (Light, 2003) and a young Ranjan Ghosh to explore her creativity in Aaha Re! (Wow! 2019).

Form and Content Too: Actor Turns Director

Roopey tomay bholabo naa – I will not entice you by looks alone, women directors have been saying for long. Thus, Manju Dey (1926-1989) not only starred in Jighansa (Blood Lust 1951), Neel Akasher Neechey (Under the Blue Sky, 1959), ’42 (1942, 1951),her Abhishapta Chambal (The Blighted Ravine, 1967) based on Tarunkumar Bhaduri’s accounts. recounted the life of legendary dacoits of Chambal who paved the way for Phoolan Devi.

Arundhati Devi, (1924-1990) the unforgettable Bhagini Nivedita (1962) who lives on through Tapan Sinha’s Kshudhita Pashan (Hungry Stones,1960), Jatugriha (1964), Harmonium (1976), turned director with Megh O Roudra (Clouds and Sunshine, 1969) to highlight a young widow’s quest for education. Apart from making Chhuti (Vacation, 1967) and Padipishir Bormi Baksho (The Burmese Casket, 1972), she also composed music for Shiulibari (The House of Jasmines, 1962) and produced Bicharak (The Judge, 1959). In her personal life the independent minded actress-director had divorced writer-director Prabhat Mukherjee to marry Tapan Sinha — later highly decorated — in the-then convention-bound Tollygunge. Prior to her only Kanan Devi, the singing star of New Theatres classics who was celebrated across India, had taken upon herself the onus of producing films, by setting up Srimati Films.

Coming after them, Madhabi Mukherjee did not produce films. But the “beautiful, deep, wonderful … (lady who) surpasses all ordinary standards of judgment” justified the praises heaped on her Charulata by not merely acting in Baishey Shraban (22nd Srabon— July-August, 2011) Mahanagar, Subarnarekha, Kapurush (The Weakling, 1965), Dibaratrir Kabya (The Poetry of Everyday Lives, 1970), Streer Patra, Biraj Bou, Utsab (The Festival, 2000). She also took on the then chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya in an election.

* Aparna Sen has been an inspiration to an entire generation of women directors. Satarupa Sanyal has garnered praise in the multiple roles of an actor, producer, director and editor. Her Anu (1998) exemplifies an idealist who is raped by the political opponents of her incarcerated fiancee. It is a crime they perpetrate, but a greater crime is perpetrated when her fiancée, Sugato, refuses to marry her because she has been raped!

* With financial help from NFDC, Urmi Chakravarty made Hemanter Pakhi (Autumn Bird, 2003). It offered another new experience. A housewife shoots into the limelight by authoring a book, but her middle-class husband and sons are not thrilled. They would rather she remained the demure housewife, cooking and caring only for them.

* Aditi Roy won Rupa Ganguly a Lotus through her Abosheshey. Meanwhile Anumita Dasgupta won awards with Jumeli (2012) that tells the story of a tribal woman whose husband turns her pain of losing her child into a business commodity. How? The only balm for her pain lies in breastfeeding newborns. So? Get her pregnant, repeatedly, and get her to abort, again and again! The impact on her health? Her morale? Her childbearing ability? Who cares!

* Now we have Nandita Roy and Sudeshna Roy. Both are creating a buzz with their co-directors Shiboprasad Mukherjee and Abhijit Guha respectively. Nandita-Shiboprasad have come out with Icche (Desire, 2011), Muktodhara ( The River of Freedom, 2012), Accident (2012), Alik Sukh ( Unreal Happiness, 2013), Ramdhanu ( Rainbow, 2014) — all of which including their latest Amar Boss (My Boss, 2024) focus on various walks of our social life, be it education, accident, medical ethics, or jail reforms.

* Sudeshna-Abhijit started with focusing on the sexually free relationship of gen-next, or the unrestricted use of abuses by urban youth, and graduated to Jodi Love Diley Na Prane (If There’s No Love, 2014), which shows that even undying love, once behind us, should be left behind. They used Chaplinesque spoof to tell the story of Hercules (2014), the power within us, which alone can give us the strength to fight bullies. Their latest Aapish (Office, 2024) recounts the plight of working women, whether they belong to the upper class or come from the suburbs.

Post Script

To conclude: Be it men or women, as director or actor, or even a writer like Suchitra Bhattacharya — they have all made it clear — that women in Bengali films are not mere sex objects. Yes, many films still use ‘item-numbers’ to titillate the male fantasy. But then, with Takhan Teish (When He Was 23, 2010), Atanu Ghosh records the attitudinal change in our men — through a woman protagonist who is a professional porn star. Rightly, then, we may say that Bengali films carry on the tradition of Kanan Bala who outclassed her humble origins to become the revered Kanan Devi.

.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and writes books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International