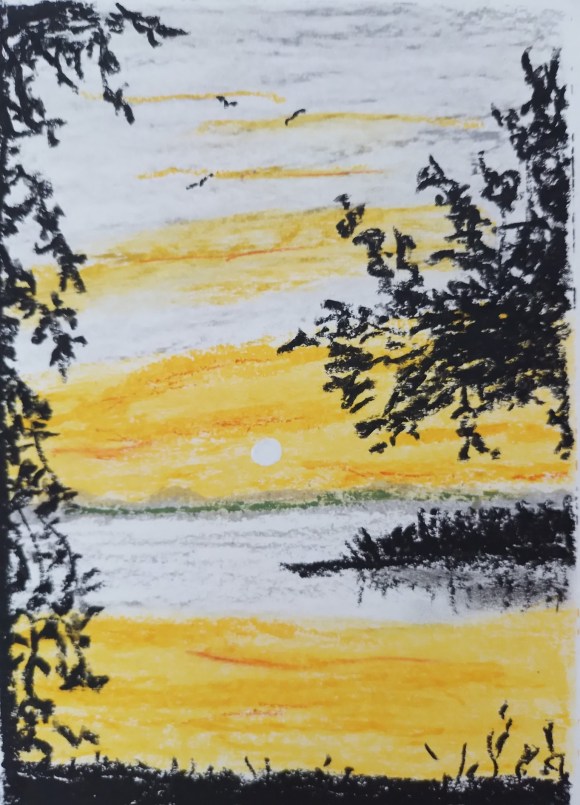

It has been a strange year for all of us. Amidst the chaos, bloodshed and climate disasters, Borderless Journal seems to be finding a footing in an orphaned world, connecting with writers who transcend borders and readers who delight in a universe knit with the variety and vibrancy of humanity. Like colours of a rainbow, the differences harmonise into an aubade, dawning a world with the most endearing of human traits, hope.

A short round up of this year starts with another new area of focus — a section with writings on environment and climate. Also, we are delighted to add we now host writers from more than forty countries. In October, we were surprised to see Borderless Journal listed on Duotrope and we have had a number of republications with acknowledgement — the last request was signed off this week for a republication of Ihlwha Choi’s poem in an anthology by Hatchette US. We have had many republications with due acknowledgment in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and UK too among other places. Our team has been active too not just with words and art but also with more publications from Borderless. Rhys Hughes, who had a play performed to a full house in Wales recently, brought out a whole book of his photo-poems from Borderless. Bhaskar Parichha has started an initiative towards another new anthology from our content — Odia poets translated by Snehaprava Das. We are privileged to have all of you — contributors and readers — on board. And now, we invite you to savour some of our fare published in Borderless from January 2025 to December 2025. These are pieces that embody the spirit of a world beyond borders…

Poetry

Click on the names to read the poems

Arshi, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal, Snehaprava Das, Ron Pickett, Nziku Ann, Onkar Sharma, Harry Ricketts, Ashok Suri, Heath Brougher, Momina Raza, George Freek, Snigdha Agrawal, Stuart Macfarlane, Gazala Khan , Lizzie Packer, Rakhi Dalal, Jenny Middleton, Afsar Mohammad, Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Rhys Hughes

Translated Poetry

The Lost Mantras, Malay poems written and translated by Isa Kamari

The Dragonfly, a Korean poem written and translated by Ihlwha Choi

Ramakanta Rath’s Sri Radha, translated from Odiya by the late poet himself.

Identity by Munir Momin, translated from Balochi by Fazal Baloch

Found in Translation: Bipin Nayak’s Poetry, translated from Odiya by Snehaprava Das.

For Sanjay Kumar: To Sir — with Love by Tanvir , written for the late founder of pandies’ theatre, and translated from Hindustani by Lourdes M Surpiya.

Therefore: A Poem by Sukanta Bhattacharya, translated from Bengali by Kiriti Sengupta.

Poetry of Jibanananda Das, translated from Bengali by Fakrul Alam.

Tagore’s Pochishe Boisakh Cholechhe (The twenty fifth of Boisakh draws close…) translated from Bengali by Mitali Chakravarty.

Fiction

An excerpt from Tagore’s long play, Roktokorobi or Red Oleanders, has been translated by Professor Fakrul Alam. Click here to read.

Ajit Cour’s short story, Nandu, has been translated from Punjabi by C Christine Fair. Click here to read.

A Lump Stuck in the Throat, a short story by Nasir Rahim Sohrabi translated from Balochi by Fazal Baloch. Click here to read.

Night in Karnataka: Rhys Hughes shares his play. Click here to read.

The Wise Words of the Sun: Naramsetti Umamaheswararao relates a fable involving elements of nature. Click here to read.

Looking for Evans: Rashida Murphy writes a light-hearted story about a faux pas. Click here to read.

Exorcising Mother: Fiona Sinclair narrates a story bordering on spooky. Click here to read.

The Fog of Forgotten Gardens: Erin Jamieson writes from a caregivers perspective. Click here to read.

Jai Ho Chai: Snigdha Agrawal narrates a funny narrative about sadhus and AI. Click here to read.

The Sixth Man: C. J. Anderson-Wu tells a story around disappearances during Taiwan’s White Terror. Click here to read.

Sleeper on the Bench: Paul Mirabile sets his strange story in London. Click here to read.

I Am Not My Mother: Gigi Baldovino Gosnell gives a story of child abuse set in Philippines where the victim towers with resilience. Click here to read.

Persona: Sohana Manzoor wanders into a glamorous world of expats. Click here to read.

In American Wife, Suzanne Kamata gives a short story set set in the Obon festival in Japan. Click here to read.

Sandy Cannot Write: Devraj Singh Kalsi takes us into the world of advertising and glamour. Click here to read.

Non Fiction

Classifications in Society by Tagore has been translated from Bengali by Somdatta Mandal. Click here to read.

The Day of Annihilation, an essay on climate change by Kazi Nazrul Islam, translated from Bengali by Radha Chakravarty. Click here to read.

The Bauls of Bengal: Aruna Chakravarti writes of wandering minstrels called bauls and the impact they had on Tagore. Click here to read.

The Literary Club of 18th Century London: Professor Fakrul Alam writes on literary club traditions of Dhaka, Kolkata and an old one from London. Click here to read.

Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein: How Significant Is She Today?: Niaz Zaman reflects on the relevance of one of the earliest feminists in Bengal. Click here to read.

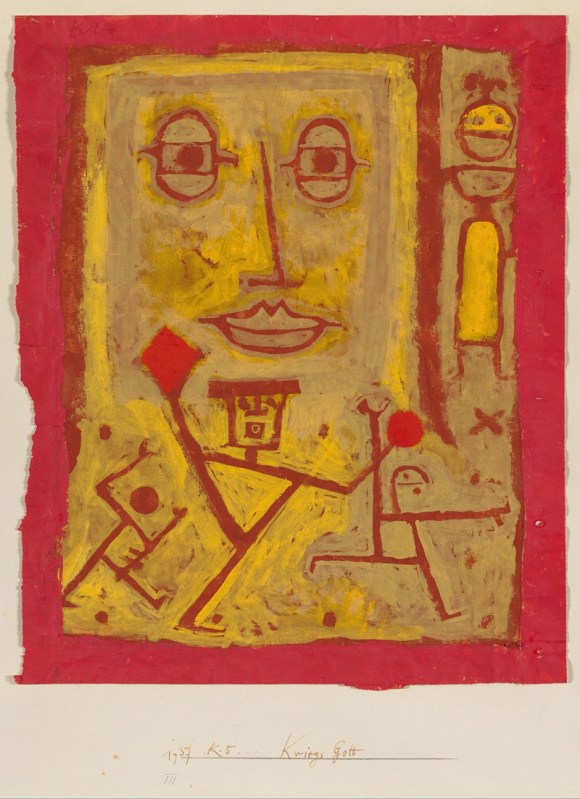

Anadi: A Continuum in Art: Ratnottama Sengupta writes of an exhibition curated by her. Click here to read.

Reminiscences from a Gallery: The Other Ray: Dolly Narang muses on Satyajit Ray’s world beyond films and shares a note by the maestro and an essay on his art by the eminent artist, Paritosh Sen. Click here to read.

250 Years of Jane Austen: A Tribute: Meenakshi Malhotra pays a tribute to the writer. Click here to read.

Menaced by a Marine Heatwave: Meredith Stephens writes of how global warming is impacting marine life in South Australia. Click here to read.

Linen at Midnight: Pijus Ash relates a real-life spooky encounter in Holland. Click here to read.

Two Lives – A Writer and A Businessman: Chetan Datta Poduri explores two lives from the past and what remains of their heritage. Click here to read

‘Verify You Are Human’: Farouk Gulsara ponders over the ‘intelligence’ of AI and humans. Click here to read.

Where Should We Go After the Last Frontiers?: Ahamad Rayees writes from a village in Kashmir which homed refugees and still faced bombing. Click here to read.

The Jetty Chihuahuas: Vela Noble takes us for a stroll to the seaside at Adelaide. Click here to read.

The Word I Could Never Say: Odbayar Dorj muses on her own life in Mongolia and Japan. Click here to read.

On Safari in South Africa by Suzanne Kamata takes us to a photographic and narrative treat of the Kruger National Park. Click here to read.

The Day the Earth Quaked: Amy Sawitta Lefevre gives an eyewitness account of the March 28th earthquake from Bangkok. Clickhere to read.

From Madagascar to Japan: An Adventure or a Dream: Randriamamonjisoa Sylvie Valencia writes of her journey from Africa to Japan with a personal touch. Clickhere to read.

How Two Worlds Intersect: Mohul Bhowmick muses on the diversity and syncretism in Bombay or Mumbai. Click here to read.

Can Odia Literature Connect Traditional Narratives with Contemporary Ones: Bhaskar Parichha discusses the said issue. Click here to read.

A discussion on managing cyclones, managing the aftermath and resilience with Bhaksar Parichha, author of Cyclones in Odisha: Landfall, Wreckage, and Resilience. Click here to read.

A discussion of Jaladhar Sen’s The Travels of a Sadhu in the Himalayas, translated from Bengali by Somdatta Mandal, with an online interview with the translator. Click here to read.

A conversation with the author in Anuradha Kumar’s Wanderers, Adventurers, Missionaries: Early Americans in India . Click here to read.

Keith Lyons in conversation with Harry Ricketts, mentor, poet, essayist and more. Click here to read.