Farouk Gulsara on a cycling adventure through battleworn Kashmir

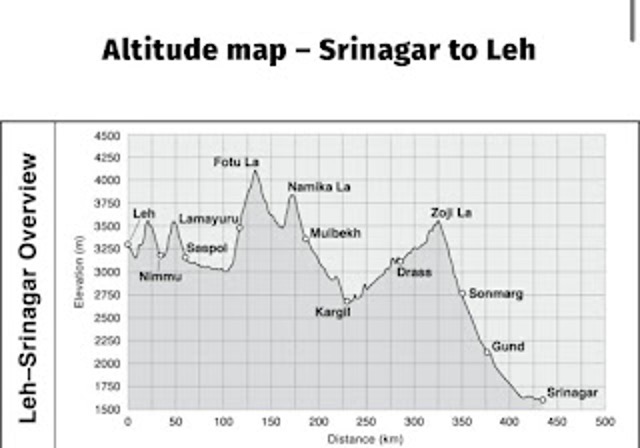

They say to go forth and explore, to go to the planet’s edge to increase the depth of your knowledge. Learning about a country is best done doing the things the local populace does, travelling with them, amongst them, not in a touristy way, in a manicured fashion in a tourist’s van but on leg-powered machines called bicycles. Itching to go somewhere after our memorable escapade in South Korea, cycling from Seoul to Busan, as the borders opened up after the pandemic, somebody threw in the idea of cycling from Kashmir to Ladakh. Long story short, there we were, living our dream. The plan was to cycle the 473km journey, climbing 7378m ascent in 8 days, between 6th July 2024 and 12th July 2024.

Our expedition started with us landing in Amritsar after a 5.5-hour flight from Kuala Lumpur. From there, it was another flight to Srinagar, where the crunch began.

Day 1. Amritsar

After a good night’s sleep, everyone was game for a quick, well-spread breakfast and a leisurely stroll to the Harmandir, the Sikh Golden Temple. Much later, I realised the offering was 100% vegetarian and did not miss any non-vegetarian food. As a mark of respect, the vicinity around the temple complex served only vegetarian food, including a McDonald’s there. Imagine a McDonald’s without the good old quarter pounder! Hey, image is essential.

The usual showing of gratitude to the Almighty was marred by the unruly behaviour of the Little Napoleons, the Royal Guards. New orders were out, it seems, according to one guard with a chrome-plated spear and a steely sheathed dagger at his hip—no photography allowed. Then, on the other end of the Golden Pool, it was okay to photograph but only with a salutary (namaste) posture, with hands clasped on the chest. On the other side, it was alright. One can pose as he pleases. The guards were more relaxed there.

That is the problem when rules are intertwined with religion. People make their own goal post and shift it as they please. When little men are given power to enforce God’s decree on Earth, they go overboard. They feel it is their God-given raison d’etre and the purpose of existence. Since nothing is cast in stone and everyone in mankind is on a learning curve, what is appropriate today may be blasphemous tomorrow and vice versa. We distinctly remember snapping loads of pictures of the full glory of Harmandir day and night during our last visit, preCovid.

We all know what happened in the Stanford experiment when students were given powers to enforce order. It becomes ugly very quickly. Next, the flight to Srinagar.

Boat House Dal Lake, Srinagar

My impression differed from when Raj Kapoor and Vyajanthimala were seen spending their honeymoon boating around the lake in the 1964 mega-blockbuster Hindi movie Sangam. Then, it had appeared insanely cold, with mists enveloping the lake’s surface. Serenity was the order of the day. What I saw in the height of summer with a temperature hovering around 30C, was anything but peaceful. Even across the lake, the constant blaring of car horns was enough to make anyone go slightly mad.

The lake is a godsend for dwellers around it. Many depend on the lake to transport tourists and sell memorabilia and other merchandise on their boats. The rows of boat houses are also popular sites for honeymooners and tourists to hire. Privacy may be an issue here. Imagine small-time Kashmiri silk vendors just landing at the boat house and showing produce to the occupants. They may want you to sample their kahwa, a traditional spiced-up, invigorating, aromatic, exotic green tea.

Day 2. Boat House, Dal Lake, Srinagar

Early morning starts with peaceful silence until the honking and murmur of the crowd start slowly creeping in. It was a leisurely morning meant to acclimatise ourselves to the high altitude (~1500m) before we began to climb daily till we hit the highest point of ~5400m. This would — aided by prophylactic acetazolamide –hopefully do the trick to keep altitude sickness at bay.

The morning tête á tête amongst the generally older crowd was basically about justifying our trip ahead. The frequent question encountered by these older cyclists was, ‘Why were they doing it?’ The standard answer was similar to what George Mallory told his detractors when he expressed his desire to climb the peak that became Everest.

“Why? Because it is there!” Mallory had said.

The cyclists told their concerned naysayers, “Because we can!”

Yeah, the general consensus was sobering. Time was running out, and so many things needed to be done before the big eye shut. There were so many places and so little time!

Continuing the easy-peasy stance before the crunch, a trip to town was due. Backed with the symphony of the blaring of honks, we made a trip to the town square, Lal Chawk. After checking out how regular people got along with life, we realised the heavy presence of armed army personnel at almost every nook and corner of the town. Perhaps it was because it was Friday and prayers were in progress.

The return trip to our boat house was a trip down memory lane. After spending most of our adult lives in air-conditioned cars, the trip back on a cramped Srinagar town bus brought us back to our childhood, when rushing to get a place in the bus and squeezing through shoulder to shoulder in a sardine-packed bus was a daily challenge. That, too, was in the tropical heat minus the air conditioning.

By noon, temperatures had soared to a roasting 30C. So much for cool Kashmir!

Our trip coincided with the Amarnath Yatra, an annual pilgrimage for Shiva worshippers who pay obeisance to Holy Ice Lingam.

The evening was the time to familiarise ourselves with our machines, which involved a ride around the city. It was a nightmare of an experience where we had to simultaneously see our fronts, back, and sides. It was jungle fare. Nobody knew from which direction vehicles were going to barge at us. We survived somehow, if ever we were born in India, our most probable cause of death would be death by road traffic accident.

The ride brought us to the affluent part of Srinagar, which changed our perception of Kashmir as a war-torn zone. What we saw were nicely manicured lawns and neatly painted buildings. The only hint of disturbances is the apparent presence of armed army personnel nearby. It is said that the one single sign of peace is to see people hanging around lakes and esplanades. We did see this on this ride. Young families were strolling along the promenade to a string of shops selling potpourri of delicacies. Kashmir appeared peaceful.

Day 3. Srinagar…move it, move it…

It was 4am in Kashmir, and all through the night, it had been raining with occasional threats of thunder in the distance. The plan was to start riding as soon as the day broke with the first ray of the sun. That could be 5am or later. And it has probably nothing to do with Indian timing. Today’s ride would be a 90km challenging ride with an ascent of 4.5%.

All the cyclists survived the ordeal. Starting around 6am, after checking the machines and last-minute briefings, we were good to go.

We did not know that Lake Dal was so huge. The first 20km was all about going around the lake. The first stop was at Mani Gam, a picturesque countryside with a massive tributary of the Sindh River, for an early breakfast of hot milk coffee.

As expected, the traffic was heavy because of the Amarnath Yatra. But one would expect attendees of a divine voyage like this to want to exhibit tolerance, patience, and softness. Unfortunately, the ugly side of drivers was in full glory. If the rest of the world would blare their honk with all their might just before a head-on collision, here, the same action is synonymous with informing another fellow road user that he is around.

To be fair, many pilgrims were in chartered vans, and the drivers were quite aggressive, overtaking in blind corners and swerving to the edge of the roads. All in the name of making more trips and making money for the family.

They say with greater powers comes great responsibility. Apparently, the lorry drivers here missed the memo. Locally, they are known as the King of the Road, with multi-octaved ear drums rupturing high-decibel honks, sometimes to the tune of Bollywood numbers.

The cyclists continued grinding despite side disturbances that can push any person raving mad; the steady climb was unforgiving. Just when they thought that was the end of the climb, they were fooled for another just after the bend. The most gruelling part was the end of the day’s trip. We rode more than 85 km, climbed a total elevation of 2692 m, and still lived to tell.

Hotel Thajwass Glacier, Sonamarg

Dinner was entirely vegetarian as a mark of respect to the hotel’s occupants who were there to fulfil their pilgrimage at Amarnath temple. The brouhaha that struck a chord amongst many occupants was the cancellation of helicopter services to the pilgrimage site. The pilgrims were given the choice of either walking a 15 or 22-km track to fulfil their vows or they could pre-book a helicopter ticket to go there. The trouble with the helicopter services is that their feasibility depended on the weather. Weather is controlled by God, the logical explanation would be that God was not too keen to give audience to the so-and-so who were scheduled on flight.

After the light chat with fellow hotel dwellers and answering their curious questions about why able bodies would want to torture themselves, it was time to hit the sack. We could have asked them why fly when they could walk, but we did not.

Day 4. Sonamarg

We decided to make it a day of light and easy. Everyone was left to their own devices after the spirit-sapping grind the day before. Most took a rain check on the initial hike but went for a long walk instead.

So, we took a stroll in the Kashmiri Valley, admiring the result of Nature’s choice of colours in His palette: the symphony of rushing cool mountain water and the refreshing cool breeze.

We met a couple from Chennai at the breakfast table with a sad tale. They had recently lost their only child who was born with cerebral palsy. They had to part from her after caring for their child for many years. They suddenly found plenty of free time on their hands. They decided to spend the rest of their remaining post-retirement lives doing short gigs, earning enough money to tour around and help out other families undergoing the same predicament as they did with their special child.

When we think we do not have nice shoes, we should not forget about those with no feet. No matter how big our problems seemed, others could have had it worse.

Sonamarg can be classified as a tourist town with rows of hotels on either side of the road, occasionally laced with souvenir shops and restaurants. The township appears to have been newly built, with freshly tarred roads, loose pebbles on the road shoulder, and unfinished touch-ups.

Day 5. Off to Drass

We were off to Drass, the coldest inhabited place in India in winter. A quick read and one might read it as Dr-Ass, rather fitting of a name as one could use an examination of one’s derrière after a climb that was upon us. We will see you in hell. But wait, hell is supposed to be hot, is it not? Or hath hell frozen over?

At one point in the 1947-48, Drass was invaded and captured by Pakistan. Soon later, India recaptured Drass. We were only 12km from the line of control (LOC).

Hotel D’Meadow Drass

As expected, it was a gruelling ride. The first 21km were excruciatingly torturous, with narrow roads that had to be shared with the notorious motorists who thought that without the honk, one could not drive. We had to test our trail biking skills later as quite a bit of the stretch was undone or probably collapsed as a result of downpours. We were left with a sand tract and later fabricated stone tracks, which gave good knocking on our posterior ends. Remember our appointment with Dr Ass?

After the 21 km mark, it was generally downhill, but our guide told us to unlock the mountain bike suspension for more comfort due to the violent bumping. The road improved as we entered Ladakh but was interspersed with occasional potholes that shook the machine.

After a short lunch break at a remote restaurant (referred to as a hotel), we were good to go and finally reached Drass at about 3 pm.

We had gone through the gruelling Zojila Pass. A tunnel is currently being built to connect Sonamarg and Drass. It would cut down travel from 4h to 1.5h.

Point to note: this Pass lives up to its name. When Japan was attacked by many post-nuclear attack monsters, the biggest one was referred to as Gojira. Hollywood decided to christian Gojira as Godzilla, giving rise to the meaning of gigantic as in Mozilla and Godzilla’s appetite. Zojila Gojira, what’s the difference? Both were scary.

Day 6. Drass to Kargil

Leaving the ‘Gateway to Ladakh’ and the ‘Coldest place in India’, we headed toward Kargil, which had been immortalised in annal of history when Pakistan and India fought a war in 1999.

Today’s cycling routine was less enduring compared to our previous rides. Most of the route was a downhill trend lined by dry, stony mountains on one side and the gushing blue waters of a tributary of the Indus on the other. The road condition was pretty good, with recently tarred roads, barring some stretches being tarred and resurfaced in various states.

After completing the close 60km trip to Kargil, we were told we were the fastest group the organiser had ridden with. Eh, not bad for a bunch of sixty-something madmen! Maybe they were just words of encouragement.

I was surprised to see Kargil as a bustling town with many business activities. Construction is happening here and there. Vendors were spreading their produce. Touters were busy looking for clientele. Hyundais, Marutis, and motorcycles thronged the streets, which were obviously not built to handle such tremendous volumes. Everyone was in a hurry. That is a sign of development.

We were housed in the tallest building around here. It was a four-story, four-star hotel with a restaurant and 24-hour hot water services. In most places we stayed, hot water was only supplied at short, predetermined intervals.

Day 7. Kargil to Budkharbu

The day started at about 6:45 am, with temperatures around 9C. This leg was expected to be tough. Two-thirds of our journey would be climbs, and there’d be more. It is expected to be sunny throughout, so we could expect a lot of huffing and puffing.

Today’s ride was easily the toughest one. Straddling on our saddles for 7.5 hours was no easy feat by any means. The climbs went on and on. The steepest and most prolonged ascent came after 39 km. It was a sustained climb for the next 10 km, hovering between 4% and 12% ascent.

Nevertheless, we were feasted with some of the most mesmerising views of barren, arid landscapes, as though someone had painted them with hues in the brown range, occasionally speckled with malachite green and a top of sky blue. It was a feeling as if we were at the edge of heaven.

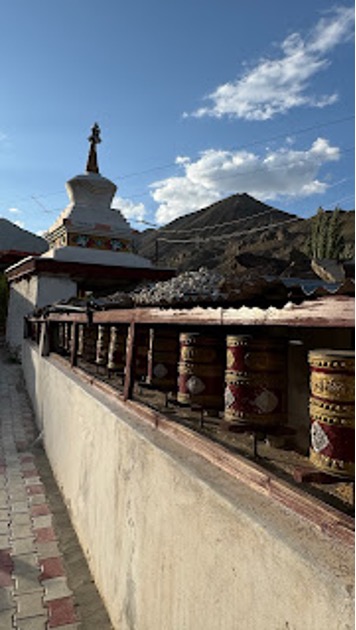

We pass through a small town called Malbech, which appears to be a Buddhist town with many temples and chanting over its public address system. I guess no one wants to keep their sacred words of God to themselves. They had a compelling desire to broadcast it to the world.

Many Shiva temples and mosques lined the road of our ride, all showing their presence with specific flags, colours and banners claiming those areas.

We finally reached Budhkharbu at 2 pm in the heat of summer Ladakh. The temperature was about 22C. The total biking time was 5h 43m. Everyone was shrivelled, depleted of glycogen and energy.

Budhkharbu is so far from civilisation that the occupants do not feel the need for digital connectivity. Only we, the town folks, were having withdrawal symptoms for not being able to upload our Strava data to earn instant gratification. Foreigners were not allowed to purchase SIM cards, so we were essentially crippled for a day.

Day 8. Padma Numbu Guest House, Budhkhorbu to Nurla

Rise and shine. Rinse and repeat. Breakfast at the Guest House to a vegetarian, sorry, no eggs too, accompanied by the aroma of incense and the tune of ‘Om Jaya Jagatheeswara Hare1‘, we were good to go. I suspect the owners of this guest house were ardent BJP supporters. The keyholder to our rooms carried a lotus symbol. And the BJP mission office was their neighbour.

We were up on the saddle and ready to move by 7:15 am. The sun was already bright and shiny by then, and we were all enticed by the 26kms steep decline.

After 9 kms, we did not mind the initial steep climb traversing the unforgiving Fotula Pass. At one point, we almost reached 4,200m above sea level. Other than the occasional passerby and military barracks, there wasn’t a single inkling of life there. It was just barren, arid land for miles and miles.

64 km later, we arrived at our destination, Nurla. Nurla is a no man’s land and is not featured for first-time visitors to Ladakh. Nearby is a self-forming statue of the Sleeping Buddha and a giant statue of Maitreya Buddha. Here, the seed of the Namgyal Dynasty started. It is famous for Tibetan paintings. As temporary sojourners, we just learned and moved along.

By now, we had learnt how the honking system worked. Even the brotherly advice from BRO (Border Road Organisation) advises using vehicle horns, especially at blind corners and overtaking another vehicle. At a telepathic level, the driver seems to converse with the other, ‘I can take charge of my vehicle as I overtake you. Now, don’t you make any sudden moves, can you?’ The melodious tone of honks, especially of lorries and buses, is just to liven up the monotonous journey, as do music (and movies).

Day 9. Travellers’ Lodge, Nurla to Leh

We were told today’s leg would be challenging, with 85 km to cover and a steep one. Hence, we had to be up on our saddles by 5 am.

In essence, today’s outing was the toughest by far. We climbed two hills, and just when we thought everything was done and dusted, another climb to our hotel came. Overall, we covered 85km and 1672m elevation in 7h 2m.

We saw two essential tourist attractions as we approached Leh: Magnetic Hill and gurudwara. Magnetic Hill is believed to create an optical illusion of a hill in the area and surrounding slopes. The cars may be going uphill when they are, in fact, going downhill.

The Guru Pathan Gurudwara is another curious worship site in the middle of nowhere. Legend has it that Guru Nanak stopped at this place, coming from Tibet and towards Kashmir. It was a Buddhist enclave. While meditating, an evil demon tried to crush him by rolling down a boulder. Hold behold, the stone turned waxy soft and did not injure the Guru.

An indestructible piece of rock was encountered while constructing this stretch of the highway. The Buddhist monks told the authorities of the legend, and the Gurudwara was erected. The Buddhists revered Guru Nanak and treated him as a great teacher.

The journey ended with a brutal, unrelenting climb to our final destination, Hotel Panorama in Leh.

The next journey the following day to Khardungla was optional. Only the young at heart opted for it. A 37 km journey with an inclination of 8% constantly with possible extreme subzero temperatures was too much to ask from my gentle heart. I opted out.

Thus ended our little cycling escapade from Srinagar to Leh, Ladakh. Few will attempt this journey with SUVs or superbikes; only madmen will do it with mountain bikes.

P.S. I want to thank Sheen, Adnan, Basil, and Samir of MTB Kashmir for their immaculate planning and supervision of the rides.

- A holy chant extolling the lord of the Universe ↩︎

Farouk Gulsara is a daytime healer and a writer by night. After developing his left side of his brain almost half his lifetime, this johnny-come-lately decided to stimulate the non-dominant part of his remaining half. An author of two non-fiction books, Inside the twisted mind of Rifle Range Boy and Real Lessons from Reel Life, he writes regularly in his blogRifle Range Boy.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International