Ratnottama Sengupta traces her bonding with Joy Bimal Roy that commenced with their birth and has wended through the warp and weft of life…

The year1955 is precious in the annals of Indian cinema. That year had seen the release of the Bengali classic, Pather Panchali in August and the Hindi evergreen, Devdas, in December. The opening month of that very year, a certain Mandakini Nursing Home in Bandra, the western suburb of Bombay had seen Manobina, wife of director Bimal Roy, give birth to a son, and Kanaklata, wife of writer Nabendu Ghosh, give birth to a daughter.

“Mita (Friend) Bina was expecting after three daughters and Kanak Boan (sister) was also in labour for the fourth time, after two sons (her first born had gone within months). And we were all praying that Mita should have a son, and Kanak should have a daughter – not the other way around!” This family lore comes from Mary Jethima, wife of music director Arun Mukherjee, first cousin of thespian Ashok Kumar.

So, every time the month of January came around, I would wonder, what if the Roys had a fourth daughter and the Ghosh family a third son? I have wondered but never needed an answer. Because? I have been ever grateful to the powers that be to have Joy as my virtual ‘twin’ born six days apart.

This bonding was forged years before our birth – when Nabendu Ghosh had watched Bimal Roy’s directorial debut, Udayer Pathey[1], in a theatre in Rajsahi, now in Bangladesh; and Bimal Roy had read Nabendu’s allegorical novel, Ajab Nagarer Kahini[2], wanting to film it before Pehla Aadmi [3]became a reality. “Never have I seen a film like this!” Nabendu had echoed what hundreds, thousands, were saying when Udayer Pathey released in 1944. And he had prayed, “If ever I get to work with this director, my dream will be fulfilled!”

Bimal Roy, on his part, had said to him, “Your writings have a graphic visual quality that is so important for cinema.” And when he took up Ashok Kumar’s offer to make Maa for Bombay Talkies, and moved to Bombay in 1951, he invited Nabendu to join him as his screen writer.

That momentous journey has moulded our lives.

*

My earliest memory of the Roys at Godiwala Bungalow on 5 Mount Mary Road is of a toy horse-drawn carriage that had come from some distant land, and a life-size doll – both properties of Joy. I would take turns to ‘drive’ the carriage through the giant hall. And the doll? It opened its eyes and shut them too and even said ‘Maw!’

Outside the bungalow was the garden, a beautiful landscape hemmed in by boulders that created nooks and corners where we children could play hide and seek. But wait, there was a swing and a seesaw too, and I had all the time in the world! There was a spoilsport well at the far end of the garden that I stayed as far away from as I could. “There are ghosts in the well!” – I remember Joy telling me in a hushed tone that was perhaps meant to fool me. But when Joy said something, could I ever doubt it?

The aforementioned giant hall indoors was dominated by an imposing photo of Jethu foregrounded by 11 identical statuettes. These dancing ladies, I later learned, were the coveted Filmfare awards he had won in his illustrious career studded with unforgettables like Do Bigha Zamin[4], Devdas, Madhumati, Sujata, Bandini. As long as he lived and for years after that, Bimal Roy was the sole ‘owner’ of that many ‘Black Ladies’. But, to a girl yet to grow up, more attractive were the Japanese beauties in colourful kimonos adorning another end of the hall. However, what struck even greater awe was a ‘mosaic’ image of Madonna that Joy had crafted while in school — at age 12? It still adorns a part of his world at 6 Mount Mary Road.

Joy had a natural gift for drawing cats: One large O, another horizontal O, a curve that was an inverted C, two bright eyes and perked up ears… How effortlessly he breathed life into the lines! Joy and Bubundi’s house is now overrun by cats but back then only two brown dogs ruled, Toto and Burikin.

*

Joy was the reason I trailed into a shooting floor for the first time in life. We were maybe seven when Benazir[5] was under production at the now-extinct Mohan Studios. As the producer, Bimal Roy need not have stood next to the camera when Meena Kumari, half lying on a mehfil-style chaise lounge, would sit up, sing a single line of a tarana, discant, and the director would say ‘Cut!’ Since the fans would all stop whirring as soon as a voice called ‘Action!’, every ‘Cut!’ was followed by the make-up person trotting up to the diva and retouching her beautiful face. How many ‘Cut!’ did we survive before Joy and I skittered off the floor? No idea. But to this day I remember the deep affection in the eyes of Jethu[6] who became an icon when Joy and I were yet to outgrow the tenth year of our lives.

We were not yet teenagers when Teesri Manzil [7] released in Bandra’s New Talkies which normally screened Hollywood films. Ma and I arrived when Joy, Bubundi and friends were heading for an evening show. I got included naturally. The super hit entertainer had smashing songs in a tautly constructed suspense tale – yet I was not floored. When I said this to Jethima[8], she said, “You are speaking like a critic Uttama!” Unknown to me, that comment had perhaps set me on the course of dissecting a film like an initiated viewer.

After our school finals, Joy took to studying Commerce at Sydenham College, while I marched on with the Arts. So, I joined the Elphinstone College where all the Roy sisters – Rinkidi, Tatudi and Bubundi – had studied English Literature. Bubundi – Aparajita is her bhalo[9] name — was in the final year of BA when I joined the institution. And after she graduated, I inherited all her books and notes. With her benign presence she has been the Didi I never had in the Ghosh house, I realised in the process of preparing the short Aparajita, for her 70th birthday.

And when she got married, just like Joy I missed classes for days and weeks. More so because my elder brother, Dipankar, married Lesley Christine around the same time. Consequently, both Joy and I were least prepared for our MA exams. Together we shared our doubts with Mouni Baba, our spiritual guide who had come from Ujjain. “Do not entertain any doubt or fear,” Baba had drilled into us. “If you utter the word ‘No’ you say that to your inner self, and you will not succeed.” This priceless lesson has been my ‘Kindly Light’, leading me on at every turn of life.

*

* Jethima passed away when the 33rd International Film Festival of India was celebrating seven accounts of Devdas in Indian cinema, in 2002. In the chill of Delhi’s winter, Joy and I sat down in the Siri Fort lawns, clung to each other and howled away, oblivious of the curious stares darting in our direction.

* Joy was in Italy when Baba passed away in December 2007. The biggest bouquet at his funeral had come from Joy.

* Along with Aparajita and Yashodhara – that’s Tatudi’s formal name – Joy had completed Remembering Bimal Roy, a centenary tribute to their father. He had commenced its shooting with Nabendu Kaku, the most authentic and reliable resource person, having been with his father from Maa (1952), through Parineeta ( Wedded, 1953), Biraj Bahu (1954), Naukri (Job, 1953) and Yahudi ( The Jewess, 1957), till the very last Bandini (1964). There was another reason, as Joy himself wrote on Baba’s 90th birthday in March 2007. “He has expressed faith in my abilities even in my darkest moments of self-doubt and always encouraged me to come out of shell and move ahead in life.”

* Year 2008. Bimal Roy’s birth centenary was round the corner. Joy and I met my friend Neelam Kapur. As director, she lost no time in scheduling the tribute in the IFFI [10] at Goa. Serendipity! That very year, IFFI also paid a homage to Nabendu Ghosh who’d passed away the previous year.

The screenings, the press conferences, the purchases, the idling on the beach – more than all of these, I recall the time we spent on a boat that had ladies from Commonwealth of Independent States dancing away to glory. While most of the guests toasted with whiskey or wine, Joy and I sipped on our mineral water. Because? It happened to be a Sunday, the one day in a week we were enjoined by Mouni Baba to forego every food except one salt free vegetarian meal before sunset!

*After Remembering Bimal Roy had been feted internationally and enhanced Joy’s fan following at home, he said to me, “Here’s the entire conversation with Nabendu Kaku. I’ve used only a few minutes of it. I’ll be glad if you can use it.”

I can never thank him enough for this generosity. For, I culled 20 minutes out of the 2-hour conversation, added clippings, posters, stills, book covers, letters, reviews and critical comments to the hour-long documentary And They Made Classics… This centenary tribute traces the unique bonding Nabendu Ghosh shared with his Film Guru.

*

But let me circle back to the birth of a Bundle of Joy and the Best of Jewels in the Roy and Ghosh families respectively.

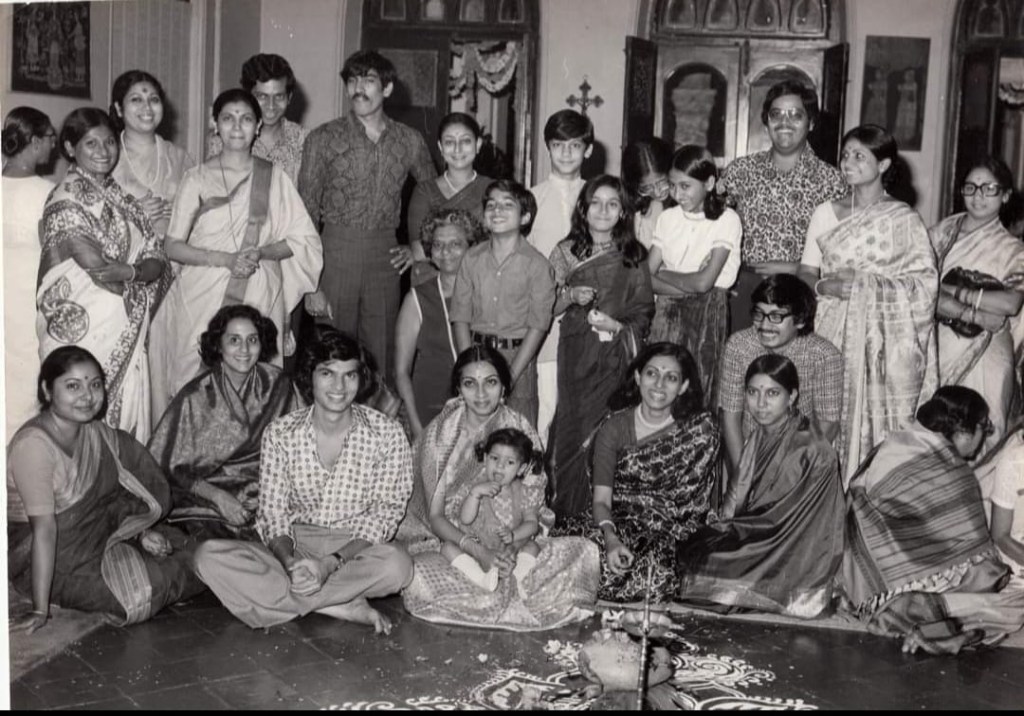

Days before 21 January 2015 Tatudi called me up. “Joy is turning 60, and how can the celebration be complete if you are not there?” Needless to add, I put on hold my preparation to retire from The Times of India just five days later, and boarded a flight bound for Mumbai. I alighted with just enough time to change into a joyous outfit, for I’ve always revered Tatudi’s good taste and Joy’s flair for dressing just right for any occasion. And was I glad I did so! For, when I reached the venue, I was speechless.

Filmmakers Behroze Gandhy and Dilesh Korya’s documentary,Kekee Manzil – The House of Art offers a glimpse into the interiors of a heritage home, shedding light on its iconic residents Kekoo and Khorshed Gandhy. Kekoo established the only picture-framing company in Asia in the 1940s and later opened the city’s first contemporary art gallery, Gallery Chemould, now known as Chemould Prescott Road, run by his daughter, Shireen Gandhy. The documentary captures how Kekoo and Khorshed displayed compassion during challenging times, stayed true to their secular ideals, and remained engaged civically, while building frameworks within which art could grow in post-colonial India.

What did I admire most? The heritage Kekee Manzil overlooking the Arabian Sea? The gathering of friends and family, including Gen-X of Bimal Roy’s team? The drinks, the amsatta paneer, the grand Birthday Cake? All of this, yes. But most of all, I will cherish for the rest of my life the taste of another cake that Tatudi and Bubundi and Joy had got. Inscribed on it were these words: “Happy Birthday Uttama!”

Some bondings start with our birth, but they live on beyond our life.

[1] On the Path of Light

[2] Tales of a Curious Land

[3] The First Man(1950)

[4] Two Acres of Land

[5] Peerless, 1964 movie

[6] Uncle, father’s elder brother

[7] Third Floor, 1966

[8] Aunt, wife of Jethu

[9] Good, but when used with name, it conveys the formal name

[10] International Film Festival of India

.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and writes books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International