By Nalini Priyadarshni

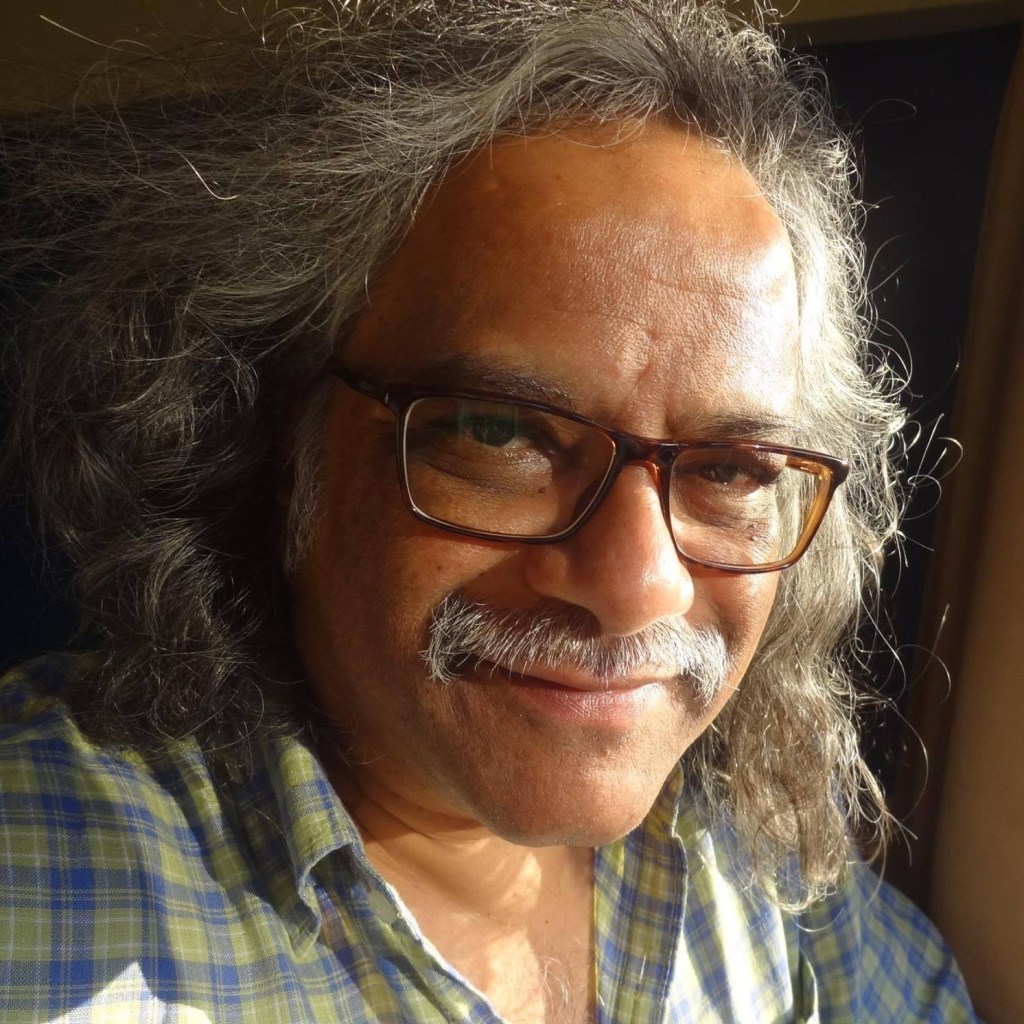

K. Sridhar is a Professor of Theoretical Particle Physics and has published a book Particle Physics of Brane Worlds and Extra Dimensions published by Cambridge University Press. He has an edited volume on Integrated Science Education and more than a hundred research papers in physics.

He is also a writer of literary fiction, has published a work of fiction called Twice Written, a critical edition of which has also been published more recently. He is working on his second novel, provisionally entitled Ajita. He writes poetry though he does not publish his poetry. He dabbles in philosophy, especially of science, and writes reviews of visual art shows. He is fond of doing lectures on rock music and writing short pieces on Hindi cinema on social media. He lives with his wife and daughter in Mumbai. Poet Nalini Priyadarshni unravels his literary journey in an online interview.

Nalini: Thank you so much, Sridhar, for taking time to talk to Borderless Journal. It’s not every day that we get a chance to read literary fiction written by an accomplished scientist. What struck me when I was reading your book was its layered narrative, story within story and eminently relatable characters. Tell us, how Twice Written began? Was it a character or an image?

K. Sridhar: Actually, neither. I think it was the concept. I should remind you that Twice Written was called ‘Palimpsest’ originally and the title was changed only before it was published. It was really the idea of a palimpsest I was working with and about lives being erased and written over. So that is where it began, I think. Of course, as I got into the actual writing, I was drawing on a fund of characters and images that I had stored somewhere in my memory to flesh out the details of the book.

Nalini: Why is the unconscious mind a writer’s best friend?

K. Sridhar: I think it is what the unconscious tosses up into one’s writing that holds a lot of surprise, not just for the reader, but also for the writer. In fact some recurrent literary elements, some shades of a character that one has not even planned out make their appearance in the writing and helps break what would otherwise be very structured prose.

Nalini: Which of your characters of Twice Written do you feel more connected with? Why?

K. Sridhar: I feel connected to all the protagonists in the story. However, one of them, Prahlad is probably closest to the person I am — his story sounds pretty much like my own. But I connect also to the other characters, not just Prahlad.

Nalini: What’s the most difficult thing about writing characters from the opposite sex?

K. Sridhar: Writing any character is a challenge, even if it is ‘someone very much like you’. But when you don’t share sex, region, temporal location, class, caste with your characters it is an even bigger challenge. My own approach is to feel the person and write as honestly as one can about the person.

Nalini: What did you like to read as a child?

K. Sridhar: As a child and as a young adult, my reading was quite eclectic. I read virtually anything I could lay my hands on. But when I was about eight or nine, I read and reread the Mahabharata in English, written by C. Rajagopalachari and really remembered every detail of it. After the age of about 16, I started reading a good amount of philosophy and books related to science. I also started reading poetry seriously around then.

Nalini: What book are you reading these days? Which contemporary writer you enjoy reading the most?

K. Sridhar: Again, I read authors who I have been reading for a long time and it is over a period of time I have read them and my respect for them grows every time I return to them. I don’t worry about their contemporaneity. As for favourites, Borges, Kundera and Calvino are right up there.

Nalini: What authors are you friends with and if they influence your writing process. If yes, how?

K. Sridhar: I have a few friends who are authors, some even very successful and well-known. But I can’t say any on them has influenced my writing. It is partly because they think of themselves as writers and of me as a scientist who writes!

Nalini: E M Forster said “the only books that influence us are those for which we are ready, and which have gone a little further down our particular path than we have yet gone ourselves.” What do you think? Is there a book that left a lasting impression on you?

K. Sridhar: If you want me to name one book, I will probably choose Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller . . .

Nalini: How do you manage being a globe-trotting scientist, an academician, an art critic, a writer and a poet? Did I miss music enthusiast and an avid movie buff?

K. Sridhar: I think I owe this as much to my wide-ranging interests from an early age as I do to the fact that I do not take any of these tags too literally. I think it also helps that I have a good deal of self-belief so I don’t find it daunting to explore a new area of interest.

Nalini: What is your writing kryptonite?

K. Sridhar: I think for any writer, it would be distraction from what one is working on. Especially for writers of fiction, I feel that distraction can be a problem. It is when one lets oneself get distracted that one could hit a block. It is something one can handle only with perseverance and discipline.

Nalini: How did publishing your first book change your writing process?

K. Sridhar: Even when I was writing Twice Written, I knew I was writing it for myself, for the pleasure of writing. The process of publishing (and republishing – the book has got republished as a critical edition) has, if at all, convinced me even more that I should be writing the way I want to and write what I believe in. If that also appeals to a readership then all the better, if not, there will always be an intimate circle who will read it and appreciate it because they know what effort has gone into it.

Nalini: Do you have any writing quirks? Would you share them with the readers?

K. Sridhar – Nothing very much. But it may interest your readers to know that I typeset my novels using a typesetting system called LaTeX which is usually used for mathematical and scientific typesetting. But because I use it so much it is like second nature to me and so I also use it to typeset my novels with.

Nalini: Do you Google yourself?

K. Sridhar: I did a bit after the novel was just out but, after a while, no.

Nalini: If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

K. Sridhar: This is a confusing question for me. I was not so young when I started writing my first novel. And now that I am deep into my second novel I don’t feel very old either. I guess I am the sort who feels that time flows like a river but it hasn’t done much beyond wetting my feet!

Nalini: Let me reconstruct my question, if you could time travel and communicate with Sridhar who had just started writing Twice Written, is there anything you would like to tell him? What would that be?

K. Sridhar: I guess it will be ‘You are off to a good start. Keep at it.’

Nalini: What words of advice do you have for writers just starting out?

K. Sridhar: I don’t want to sound pretentious and “advice” aspiring writers but I think it is good to remember that one writes for oneself. One cannot start writing by positing an imagined reader.

Nalini: Thank you so much once again. It was a pleasure talking to you.

(This interview was conducted via email.)

Nalini Priyadarshni is a feminist poet, writer, translator, and educationist though not necessarily in that order who has authored Doppelganger in My House and co-authored Lines Across Oceans with late D. Russel Micnhimer. Her poetry, prose and photographs have appeared in numerous literary journals, podcasts and international anthologies including The Lie of the Land published by Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi. A nominee for the Best of The Net 2017 she lives in Punjab, India and moonlights as a linguistic consultant.