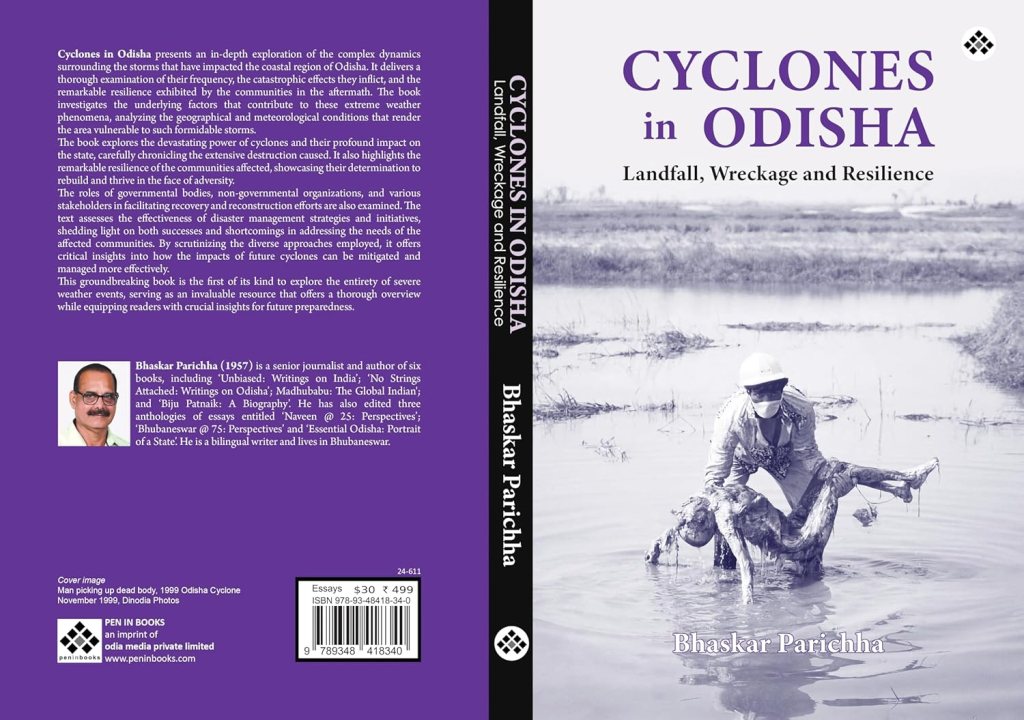

A discussion with Bhaksar Parichha, author of Cyclones in Odisha, Landfall, Wreckage and Resilience, published by Pen in Books.

While wars respect manmade borders, cyclones do not. They rip across countries, borders, seas and land — destroying not just trees, forests and fields but also human constructs, countries, economies and homes. They ravage and rage bringing floods, landslides and contamination in their wake. Discussing these, Bhaskar Parichha, a senior journalist, has written a book called Cyclones in Odisha, Landfall, Wreckage and Resilience. He has concluded interestingly that climate change will increase the frequency of such weather events, and the recovery has to be dealt by with regional support from NGOs.

Perhaps, this conclusion has been borne of the experience in Odisha, one of the most vulnerable, disaster prone states of India, where he stays and a place which he feels passionately about. Centring his narrative initially around the Super Cyclone of 1999, he has shown how as a region, Odisha arranged its own recovery process. During the Super Cyclone, the central government allocated only Rs 8 crore where Rs 500 crore had been requested and set up a task force to help. They distributed vaccines and necessary relief but solving the problem at a national level seemed a far cry. Parichha writes: “As a result, the relief efforts were temporarily limited. To accommodate the displaced individuals, schools that remained intact after the cyclone were repurposed as temporary shelters.

“The aftermath of the cyclone also led to a significant number of animal carcasses, prompting the Government of India to offer a compensation of 250 rupees for each carcass burned, which was higher than the minimum wage. However, this decision faced criticism, leading the government to fly in 200 castaways from New Delhi and 500 from Odisha to carry out the removal of the carcasses.”

He goes on to tell us: “The international community came together to provide much-needed support to the recovery efforts in India following the devastating cyclone. The Canadian International Development Agency, European Commission, British Department for International Development, Swiss Humanitarian Aid Unit, and Australian Government all made significant contributions to various relief organisations on the ground. These donations helped to provide essential aid such as food, shelter, and medical assistance to those affected by the disaster. The generosity and solidarity shown by these countries underscored the importance of global cooperation in times of crisis.” They had to take aid from organisations like Oxfam, Indian Red Cross and more organisations based out of US and other countries. Concerted international effort was necessary to heal back.

He gives us the details of the subsequent cyclones, the statistics and the action taken. He tells us while the Bay of Bengal has always been prone to cyclones, from 1773 to 1999, over more than two centuries, ten cyclones were listed. Whereas from 1999 to 2021, a little over two decades, there have been nine cyclones. Have the frequency of cyclones gone up due to climate change? A question that has been repeatedly discussed with ongoing research mentioned in this book. Given the scenario that the whole world is impacted by climate disasters — including forest fires that continue to rage through the LA region in USA — Parichha’s suggestion we build resilience comes at a very timely juncture. He has spoken of resilience eloquently:

“Resilience refers to the ability to recover and bounce back from challenging situations. It encompasses the capacity of individuals, communities, or systems to withstand, adapt, and overcome adversity, trauma, or significant obstacles. Resilience involves not only psychological and emotional strength but also physical resilience to navigate through hardships, setbacks, or crises.

“Resilience is the remarkable capacity of individuals to recover, adapt and thrive in the face of adversity, challenges, or significant life changes. It is the ability to bounce back from setbacks, disappointments, or failures, and to maintain a positive outlook and sense of well-being despite difficult circumstances.

“Resilience is not about avoiding or denying the existence of hardships, but rather about facing them head-on and finding ways to overcome them. It involves developing a set of skills, attitudes, and strategies that enable individuals to navigate through difficult times and emerge stronger and more capable.”

He has hit the nail on the head with his accurate description of where we need to be if we want our progeny to have a good life hundred years from now. We need this effort and the ability to find ways to solve and survive major events like climate change. Parichha argues Odisha has built its resilience at a regional level, then why can’t we? This conversation focusses on Parichha’s book in context of the current climate scenario.

What prompted you to write this book?

Odisha possesses an unfavorable history of cyclones with some of the most catastrophic storms. People suffered. My motivation stemmed from documenting this history, emphasising previous occurrences and their effects on communities, infrastructure, and the environment.

What kind of research went into this book? How long did it take you to have the book ready?

The idea for the book originated more than a year ago. It was intended for release to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1999 Super Cyclone and the cyclones that followed. Having witnessed the disaster first-hand and having been involved in the audio-visual documentation of the relief and rehabilitation initiatives in and around Paradip Port after the Super Cyclone, I gained a comprehensive understanding of the topic. The research was largely based on a thorough examination of the available literature, which included numerous documents and reports.

Promptly after you launched your book, we had Cyclone Dana in October 2024. Can you tell us how it was tackled in Odisha? Did you need help from the central government or other countries?

Cyclone Dana made landfall on the eastern coast on the morning of October 25, unleashing heavy rainfall and strong winds that uprooted trees and power poles, resulting in considerable damage to infrastructure and agriculture across 14 districts in Odisha. Approximately 4.5 million individuals were affected. West Bengal also experienced the effects of Cyclone Dana. After effectively addressing the cyclone’s impact with a goal of zero casualties, the Odisha government shifted its focus to restoration efforts, addressing the extensive damage to crops, thatched homes, and public infrastructure. The government managed the aftermath of the cyclone utilizing its financial resources.

Tell us how climate change impacts such weather events.

Climate change significantly influences weather events in a variety of ways, leading to more frequent and intense occurrences of extreme weather phenomena. As global temperatures rise due to increased greenhouse gas emissions, the atmosphere can hold more moisture, which can result in heavier rainfall and more severe storms. This can lead to flooding in some regions while causing droughts in others, as altered precipitation patterns disrupt the natural balance of ecosystems.

What made people in Odisha think of starting their own NGOs and state-level groups to work with cyclones?

The impetus for establishing non-governmental organisations and state-level entities in Odisha is fundamentally linked to the region’s historical encounters with cyclones, which have highlighted the necessity for improved community readiness. Through the promotion of cooperation between governmental agencies and civil society organisations, Odisha has developed a robust framework that is adept at responding to natural disasters while simultaneously empowering local communities.

What are the steps you take to build this resilience to withstand the destruction caused by cyclones? Where should other regions start? And would they get support from Odisha to help build their resilience?

Building resilience to withstand the destruction caused by cyclones involves a multi-faceted approach that encompasses infrastructure development, community engagement, and effective disaster management systems. Odisha has established a robust model that other regions can learn from. Odisha’s experience positions it as a potential leader in sharing knowledge and best practices with other regions. The state has demonstrated its commitment to enhancing disaster resilience through partnerships with international organisations and by sharing its model of disaster preparedness with other states facing similar challenges. Odisha can offer training programs and workshops based on its successful strategies, guide in implementing early warning systems, building resilient infrastructure and also collaborating with NGOs and international agencies to secure funding for resilience-building initiatives in vulnerable regions.

You have shown that these cyclones rage across states, countries and borders in the region, impacting even Bangladesh and Myanmar. They do not really respect borders drawn by politics, religion or even nature. If your state is prepared, do the other regions impacted by the storm continue to suffer…? Or does your support extend to the whole region?

Odisha is diligently assisting its impacted regions through comprehensive evacuation and relief initiatives, while adjacent areas such as West Bengal are also feeling the effects of the cyclone. The collaborative response seeks to reduce damage and safeguard the well-being of residents in both states. Odisha’s approach to cyclone response has garnered international acclaim.

Can we have complete immunity from such weather events by building our resilience? I remember in Star Wars — of course this is a stretch — in Kamino they had a fortress against bad weather which seemed to rage endlessly and in Asimov’s novels, humanity moved underground, abandoning the surface. Would you think humanity would ever have to resort to such extreme measures?

The idea of humanity seeking refuge underground, as illustrated in the writings of Isaac Asimov, alongside the perpetual storms on Kamino from the Star Wars franchise, provokes thought-provoking inquiries regarding the future of human settlement in light of environmental adversities. Although these scenarios may appear to be exaggerated, they underscore an increasing awareness of the necessity for adaptability when confronted with ecological challenges. The stories from both Kamino and Asimov’s literature act as cautionary narratives, encouraging reflection on potential strategies for human resilience in the future.

With the world torn by political battles, and human-made divisions of various kinds, how do you think we can get their attention to focus on issues like climate change, which could threaten our very survival?

A comprehensive strategy is crucial for effectively highlighting climate change in the context of persistent political conflicts and societal rifts. Various methods can be utilised to enhance public awareness, galvanise grassroots initiatives, promote political advocacy, emphasise economic prospects, frame climate change as a security concern, and encourage international collaboration.

Can the victims of weather events go back to their annihilated homes? If not, how would you suggest we deal with climate refugees? Has Odisha found ways to relocate the people affected by the storms?

Individuals affected by severe weather events frequently encounter considerable difficulties in returning to their residences, particularly when those residences have been destroyed or made uninhabitable. In numerous instances, entire communities may require relocation due to the devastation inflicted by natural disasters, especially in areas susceptible to extreme weather conditions. Odisha’s proactive stance on disaster management and community involvement has greatly improved its ability to address challenges related to cyclones. The state’s initiatives not only prioritise immediate evacuation but also emphasize long-term resettlement plans to safeguard its inhabitants against future cyclonic events. For instance, residents from regions such as Satabhaya in Kendrapara district are being moved to safer locations like Bagapatia, where they are provided with land and support to construct new homes. This programme seeks to reduce future risks linked to coastal erosion and flooding.

Thanks for your book and your time.

(This review and online interview is by Mitali Chakravarty.)

Click here to read an excerpt from the book.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International