By Ravibala Shenoy

“He was badly beaten in lockup, denied medicine, and died soon after,” my cousin writes in his article on our Uncle Anand in a local Indian publication.

“Uncle A. died of dysentery,” I respond via WhatsApp. “He was only eleven or twelve. Not fourteen as you state. And my father was eight at the time. It says so in my father’s writings.” Later in life, my father had kept notes on his brother’s death.

My cousin hesitated. “I have it on the evidence of Aunt S.,” Aunt S. is our only surviving relative from that generation. “She told me that the police warned our grandfather, that they were watching Uncle A. They finally arrested him. They threatened our grandfather into silence.”

“With all due deference,” I say, because my cousin is nine years older than me, “Aunt S. was just a few weeks old in August 1930. She hardly counts as an eyewitness. And neither you nor I were alive then.”

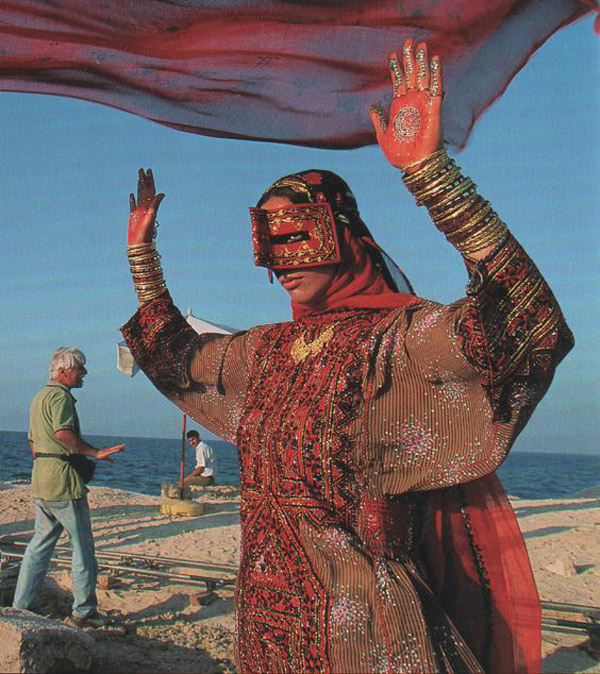

1930 was the year of Mahatma Gandhi’s civil disobedience movement. Mahatma Gandhi led the fight for independence from the British Empire by nonviolent means. Even in the small coastal town of Karwar, men and women joined in the struggle. Uncle A. with a natural flair for leadership organised the “monkey brigade” that was made up of youngsters. Townspeople hinted to my grandfather that his son, who was leading boys and girls every morning in the dawn marches, was perhaps neglecting his studies. To which my grandfather replied that his son was very smart and secured the first rank in class.

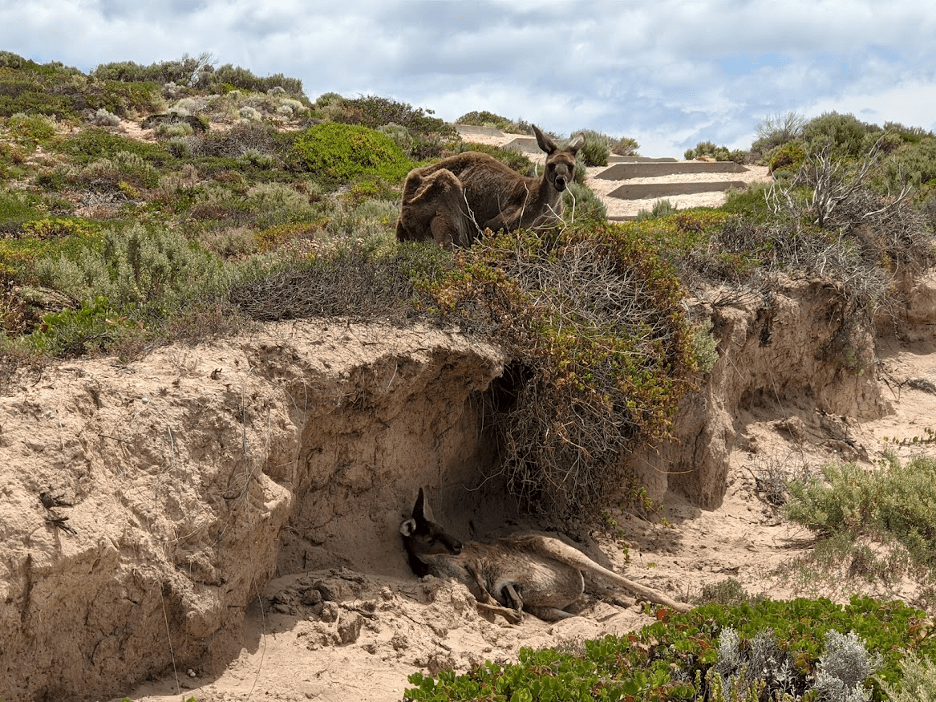

These dawn marches were accompanied by stirring patriotic songs, punctuated by lusty salutations to Mother India, Mahatma Gandhi, and Jawaharlal Nehru. Boys and girls accompanied Uncle Anand to the sea to produce salt out of seawater in defiance of the law. Making salt was a government monopoly. The spirit of swadeshi, of boycotting foreign goods for domestic ones, was in the air and Uncle A. learned how to make soap and taught it to others. He acquired a spinning wheel and showed his family how to spin cotton into yarn on a spindle. The finished yarn was mailed by Uncle A. in a parcel to the handlooms of Nandangadda.

The movement slackened a bit with the advent of the monsoons, and then in August 1930, Karwar was struck for the first time by an epidemic of dysentery.

I write to my cousin, “Uncle A. was not arrested or beaten. He was the first one to contract dysentery. Would you like to see my father’s writings?”

Dysentery was still an unfamiliar disease for the doctors in Karwar. The family doctor was very competent, and he gave Uncle A. the best treatment he knew. There were no antibiotics then. The family doctor believed that another doctor had the penicillin that could save Uncle A. He asked our grandfather to approach him, but the second doctor did not oblige. It was alleged that he was saving it for his own patients. (Our grandfather never forgave this second doctor.) Perhaps he never had any penicillin in the first place.

In the night of the fourth day of the attack, Uncle Anand died. Unexpectedly, the cloth made of yarn that he had spun arrived from Nandangadda on the morning of the funeral. It covered his body like a shroud as he was led to the cremation ground. The town held a large public meeting to mourn the death of Uncle A.

Several people died in the epidemic. My father also had a long brush with the disease, but he survived because this time the family doctor was able to acquire the penicillin.

I wonder why my cousin wants to falsify facts and revise history because that often results in making people believe none of it. This is how myths are born. Was dying from police brutality more tragic or glamorous than dying of dysentery? To me this was like an important intervention between historiography and the “woke” debate.

My cousin resents my contradicting him. Did I, a girl, albeit a grandmother now, younger than him, dare impugn his credibility? I was the unpatriotic one, removed from her heritage, a U.S. citizen who lived in the West with a westernized preciosity that downplayed the brave deeds of Indian patriots. How could I know better?

My beef with my cousin is that he doesn’t check his facts and seeks out the sensational. My cousin’s “facts” came via an aunt whose information was based on hearsay because my grandparents never spoke of the tragedy that had befallen them.

In my cousin’s defense, I must admit that I have my biases too: I hero-worship my father and regard him as the custodian of historical truth; could he have overlooked the arrest and police brutality in recording his brother’s short but heroic life? My father’s memory could just as easily have been distorted.

I also had a grievance. On my ninth birthday, my cousin had snatched my new water colour set before I even had a chance to open it and mixed up the coral with the ultramarine and the white with the green. Maybe I found it hard to believe him.

We are in agreement on one point: that my grandparents could never bear to utter Uncle A.’s name again. His name “Anand” meant “joy”—and after his death the word was forevermore excised from their vocabulary.

Once, during one of my subsequent visits to Karwar, I came across a concrete till. It stood in the shadow of the road, at some distance from my grandparents’ house. The till had a slit for coins, and a sign asking for donations for the oil needed to light the lamp for the Brahma. The Brahma was believed to be the spirit of an unmarried Brahmin youth who haunted peepul trees and coconut palms. I suspect this was a ghost that predated Uncle A.

Then it struck me. The reason for the lamp for the Brahma was to memorialise the dead so that they were not forgotten. It was a way of bearing witness to their lives and the unrealised potential of their lives. Similarly, my cousin’s write-up on Uncle Anand was like a lamp that had been lit to rescue his memory from the jaws of oblivion. If some facts had been embellished for a “good story,” it was all part of the homage.

Ravibala Shenoy has published award-winning short stories, short stories, flash fiction, memoir, and op-ed pieces. She was a former librarian and book reviewer, who lives in Chicago.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL