Ratnottama Sengupta introduces and converses with a photographer who works at the intersection of art and social issues, Vijay S Jodha

Vijay S Jodha was yet to become one of India’s leading lens-based artists at the intersection of art and social issues. Back then, in the 1990s, he had no inkling that 30 years later he would be the chairperson of UGC-CEC[1] jury for selecting the best educational films made in India. Or that he would be the national selector and trainer in photography for the National Abilympics Association of India.

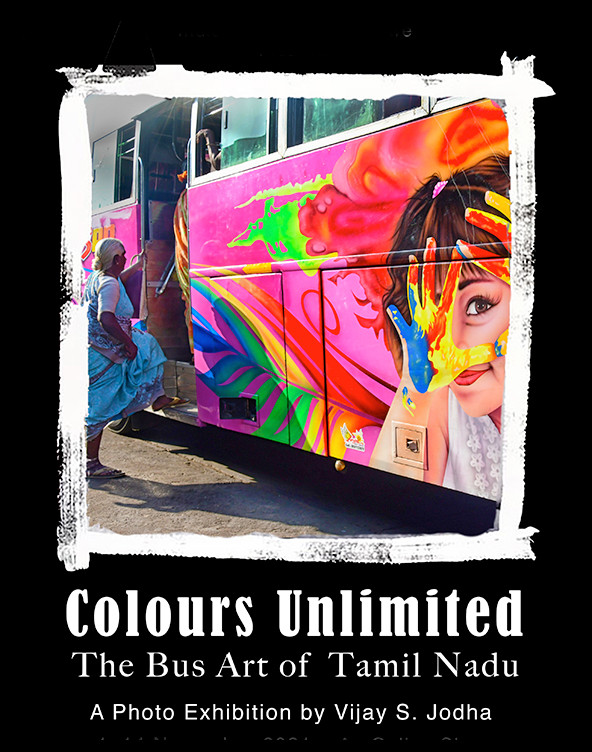

When I first met him, he was mounting a collaborative exhibition of his work with the elderly, their contribution to society and the care they deserve. Little did I know that the entire bent of this journalist-turned documentary filmmaker-turned photo artist would go on to focus on subjects ranging from mob violence, riot victims, farmers’ suicide, 75 years of Indian constitution to Joys of Christmas and the Bus Art of Tamil Nadu.

Not surprising that the International Confederation of NGOs has honoured Vijay with the Media Citizen Award for using media to drive social change. And it is only one among hundreds of honours he has received in two dozen countries. These include awards and grants, from Swiss Development Agency to Ford Foundation and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Screening of his films on 75 channels worldwide and in 250 festivals in 60 countries.

These seem tedious details? So, interestingly, two public showings of his work have been vandalised. And a false police case against him took eight years to be thrown out by India’s courts!

Conversation

Vijay how did you come into photography?

I’m a trained filmmaker – I mastered in film production – and have been making films for two decades. My films have shown on 75 stations including Discovery, CNN, BBC. But training in photography I have none. All my photography is non-fiction work. Actually my films are also non-fiction or reality based work. I just find still photography very relaxing because, unlike films where a director is responsible for so many things, here I’m on my own. But there’s no production deadline. No huge budget is needed. I can address any subject that catches my fancy and pursue it over several years, without any worry. Otherwise it’s the same: photos or films, you’re storytelling around substantial issues that interest you, in a manner that does justice to those issues, and — hopefully — engaging to the viewers.

So who was your inspiration?

In photography it is obviously the greats who defined the grammar of the medium itself such as Robert Frank[2] and Cartier Bresson[3]. They’ve inspired us all in some manner. I’m fortunate that, as a part time journalist in New York decades ago, I got to meet and interview top filmmakers and photographers like Gordon Parks and Richard Avedon.

I once did a course at New York’s School of Visual Arts where they honoured Mary Ellen Mark and she had come across. As a journalist, I covered Sebastião Salgado’s launch of his workers’ project that put him on the map (of photography). I met Raghubir Singh while doing a project on Ayodhya in India, and again in New York where we put up the same exhibition. He also photographed some of us – myself, Siddharth Varadarajan, the editor-publisher of The Wire who was then a student at Columbia University, and other Indian students — were protesting some human rights issue.

I’m also fortunate to have our finest photo-journalists and lens-based artists as friends. I can take across my work to get a feedback or pick their brains. This beats the best photo schools in the world. In fact years ago I did a book which had photos from all of them! This was the biggest photo project on the Tiranga[4] as listed in the Limca Book of Records. They have all done many books on their own but this is the only one where all these masters appear in a single volume, their works united thematically. Apart from Raghu Rai, Ram Rahman, Prashant Panjiar, Dayanita Singh, T Narayan, and the late TS Satyan, I’d also interviewed people across India, from the then Prime Minister Vajpayee to those selling flags at traffic lights for a few meagre rupees.

You did not go to any international school to train in the art or the technology aspect. So what prompted your PhD?

Three decades back when I decided to go into mass communication as a career there were few computers, no internet, no private TV channels, or mobile phones. Sorry if that makes me seem Jurassic but it was a world with very few media opportunities. Post college, I had got admissions into a trainee programme with a newspaper as well as in the MA programme in International Relations at India’s premier Jawaharlal Nehru University. My father felt that a masters and exposure at JNU would be a better investment for journalism – probably the single best advice I’ve got in my entire career — and I followed that.

Then for some time I worked in print media: I freelanced for newspapers, edited and published a journal for a business house, scripted for a film and worked on a book with one of my journalism heroes – late Kuldip Nayar. But in the pre-internet era newspaper articles had a very short life, so I felt the need to produce something that would last longer such as film. So I decided to get a degree in Film. It also encompassed all my interests, from writing to art to music, travel and photography.

You’ve not been a photo-journalist working for any journal or newspaper. Yet you felt inclined to do projects on environment, elder care, survivors of riots and mob violence, farmer suicide, art that travels. Was it inevitable, given your father’s background?

Actually I’ve done a bit of photo journalism too. During my film school days at NYU I was a writer-photographer for their student-run newspaper, Washington Square News. I’ve also been a stringer for mainstream dailies including The Economic Times where I shot images parallel to my writing. I did stills for Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding and of course stills for my own film projects. So I’ve a lot of published images in papers worldwide though my main gig has been films.

Frankly I don’t see much difference between these mediums. Be it words, stills or moving images; an academic paper, photo books, or films, short or long – all this is story telling. I’m a story teller.

And subjects? I’ve filmed every possible subject except wildlife: I just don’t have the patience for that. Otherwise everything, from artist biopics — on Paritosh Sen and Prokash Karmakar, whose inaugural screening you also attended in Calcutta years ago — to films on environment. My The Weeping Apple Tree (2005) was among the first ones on climate change in India. It won the UK Environment Film Fellowship Award 2005 and had multiple screenings on Discovery, with an introduction by Sir Mark Tully.

At that time, few knew about climate change. So Delhi govt organised a special screening for their MLAs and officers of water, electricity and sanitation departments. It was screened at UNEP headquarters in Nairobi and in various festivals. UNIDO and other grassroots level NGOs used it to create awareness. Some years back an IFS {Indian Forest Service} officer told me that Himachal government uses it to train their forest officers.

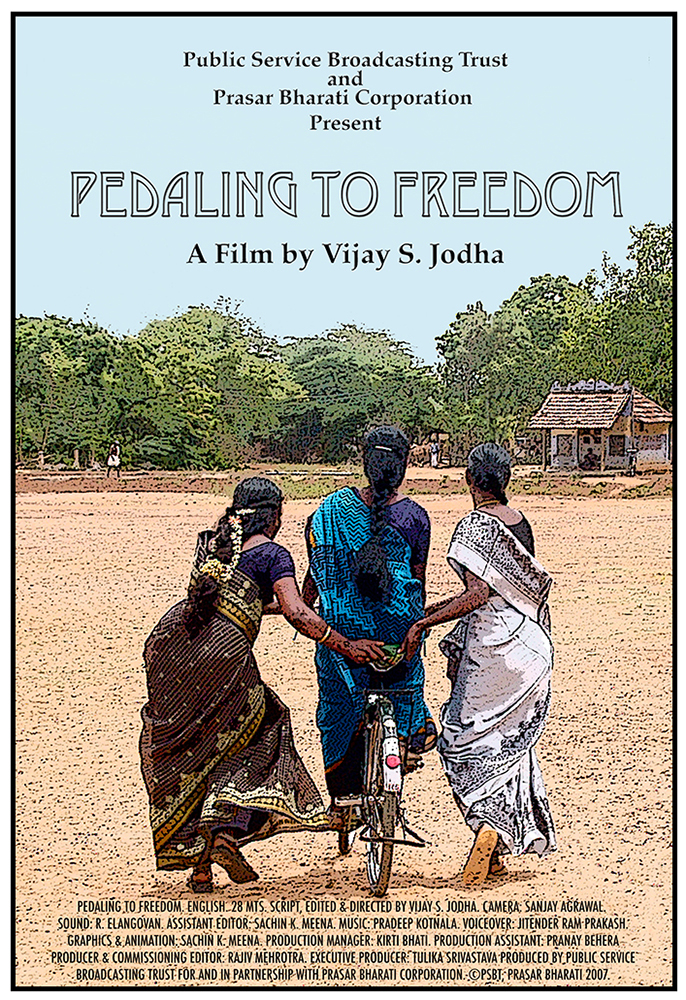

My film on gender, Pedalling to Freedom (2007) revisited an old initiative in one of the poorest parts of the world. It traced the life-changing impact of teaching 100,000 women to ride the bicycle. That film is in the US Library of Congress. It was also chosen for archiving at OSA Budapest, world’s premier repository of materials dealing with human rights.

Then there are films that get food on the table. Training films. Corporate films. I once did a ‘funeral film’ on a well-known personality whose passing received a lot of press coverage in India but the NRI son could not come for the funeral.

What motivates you Vijay — money, international honour, or the possibility of social change?

Well, all this is livelihood so the money part is important. But doing work that gets recognised far and wide, that is substantial, to hold good for a long time – that’s a huge motivator.

I have a slightly spiritual take towards this. I feel that regardless of our profession we are all bound by a dharmic or sacred duty. A teacher’s duty is to teach and a doctor’s is to heal. For those in the business of storytelling — including photographers — the sacred duty is to document, bear witness, push things forward. And believe you me, this has little connect with means or accessibility.

To give you an extreme example: After the Nazis lost the war and Berlin fell, soldiers from the victorious allies army raped virtually every woman in Berlin. Few rapists were taken to task and to top it, despite all the extensive coverage of the allies victory by forgotten photographers as well as superstars like Margaret Bourke-White (known to us through her famous Gandhiji with charkha portrait) or Robert Capa (regarded as the greatest war photographer of all time), there was no coverage of this mass outrage in Berlin by anyone be it in photo essays in Life Magazine, or World War photo books. It appears in no Hollywood film or TV series.

Likewise, fifty years ago, when India came under the draconian Emergency, our courts also endorsed the robbing of our Constitutional rights. Nobody documented, then or since, the forced sterilisation of 6,000,000 who were stripped of their reproductive rights. We, as photographers and filmmakers, failed on this front.

The First Witnesses is my project around farmer suicides. It is not an unheard issue nor something hard to get access. But how many have found it worth their while to document the issue? How many are documenting a disappearing art form or livelihood? Or our urban heritage being torn down? Our movie theatres once represented cinema as an inexpensive and readily accessible mass culture. Now they are being torn down even in smaller towns. Each had a unique character. Is anyone documenting that?

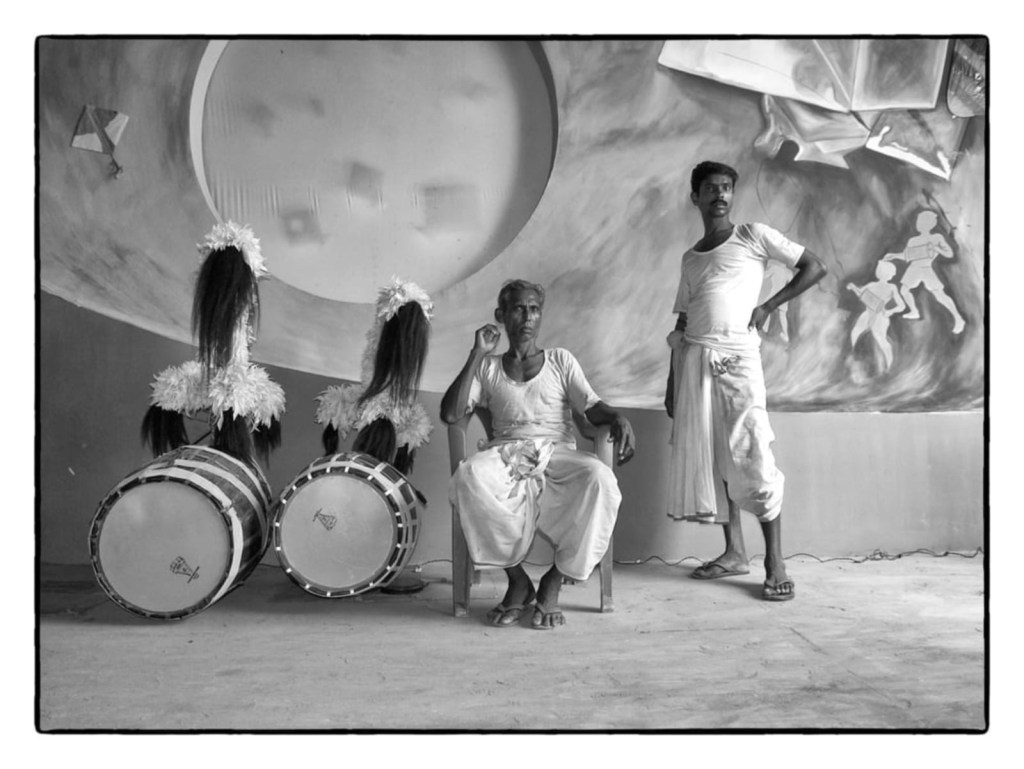

I documented Durga Puja in Kolkata 20 years ago when I was working with painters there. Durga astride a tiger, slaying the demonic Mahisasur emerging out of a buffalo: these elements get interpreted in hundreds of ways across the city each year. Each pandal has a different aesthetic interpretation, inside and outside. The religious aspect is no less important. But these are also like site-specific installation art works shaped by the imagination of so many talented people but designed for impermanence. How many books of photos exist around this work now recognised by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity?

How successful have you been in achieving this?

The merit of my work is for others to judge. I’m happy that, though India doesn’t have many foundations or support for non-commercial oriented art, I’ve been able to do at least a few things that are genuinely pathbreaking, substantial and have gone around the world. To be invited to UNESCO headquarters in Paris to screen a film and address delegates from 193 countries, or be honoured by our President for India’s best ever performed at Abilympics — these are certainly my career highlights.

My work has received over a hundred honours across 24 countries, but what truly motivates me is when people I look up to, my heroes, appreciate what I do. That kind of recognition carries a different weight. For instance, Magsaysay awardee P Sainath, whose ground-breaking reportage has long inspired me, saw my farmers project when it was exhibited alongside his photographic work at the Chennai Photo Biennale 2019. We hadn’t met before, so when he praised my effort, it felt like receiving a medal.

Another moment that has stayed with me was post my time at NYU. My professor, George Stoney, referred to as the father of public access television and mentioned in history books on documentary cinema, mentored Oscar-winning directors like Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, and Ang Lee. When he watched The Weeping Apple Tree, he said, “Vijay, this is better than Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. That was a glorified PowerPoint by comparison.” That one comment meant more to me than most awards ever could.

As a photo artist what is the biggest moment of joy for you — technical hurray or the joy of the subjects?

As I just said, recognition and praise of my heroes gives the maximum joy. There are other honours. Two photo projects listed in Limca Book of Records for being the biggest and path breaking. The first was on ageing that I did over eight years with my brother Samar Jodha – he did the images while I did the concept research, writing and interviews. The other was the aforementioned Tiranga. My film Poop on Poverty (2012) won a Peabody award, the oldest honour for documentary films, and more international honours than any non-fiction film produced out of India.

After landmark exhibitions in Hong Kong and New York I donated two complete sets of The First Witnesses, my farming crisis project, to two farmer unions including our oldest and biggest All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS). They are using it for awareness raising across villages. That’s a real high as a photographer.

Then there’s high coming from those we pass down our expertise to. Among those I’ve taught or mentored is a highly talented though physically challenged youngster from Vijayawada with missing digits and motoring issues. His family runs a Kirana shop. When he started school, they sent him back saying he cannot even hold a pencil. He won a bronze medal in photography for India at the last Abilympics in France. Another student has himself become a photography teacher in a school for hearing impaired. This is the kind of stuff that gets me very excited.

Thirty years ago as a volunteer writer and researcher I helped Sanskriti Foundation set up India’s first international artist retreat. That novel venture raised crores in grants and set up three museums. Today it is being scaled back as its founder O P Jain is in his 90s. But that idea caught on and you have scores of artist retreats across India.

How has digital technology influenced photography as an art form? Has it done more harm? Or widened its spread?

Digital has been a mixed experience. It democratised the process of production and dissemination — be it still images or movies. This is a fantastic thing. But it killed a lot of the processes and livelihoods such as the printing labs, film production and processing facilities. It has also killed an art form like print making. It’s a specialised skill in itself, so a lot of artistry, understanding, appreciation and sustenance of it has got compromised.

The emergence of deep fake images and piracy of work is bad news too. But it has allowed more people to become story tellers. They now bear witness, as filmmakers and photographers, of issues and events that was earlier impossible.

I can cite examples from my work. I’m National Selector and Trainer in photography for National Abilympics Association of India (NAAI) and my students are in different parts of India. Two are hearing impaired, two others have motoring issues and physical challenges. Thanks to digital tools, we’re running long distance classes every week. NAAI provides me sign language interpreter but I can send and receive digital files, use zoom to conduct classes, use google translate to send instructions in Tamil, English and Marathi to my students. Now one student, despite hearing challenge, is running a photo studio. The student who has issues with his leg also works as wedding photographer. Workshops with institutions and festivals, within and outside India, are now easy and inexpensive thanks to these digital tools and communication modes.

Has selfies on mobile camera shortened the life of portraiture?

It has certainly democratised the process while the average person’s patience to study or appreciate any art work — portrait or landscape photo — is shrinking by the minute. Of course, good portraiture requires some skill to make as well as appreciate – that cultural literacy is a challenge everywhere, not just in photo medium. As a seasoned art critic you would have noticed that in the world of painting and sculpture too. Sadly we don’t have that education in our schools.

You have continued with still images even after doing many documentaries. What is the joy in either case?

I’m doing still photography and movies parallel to each other. Last month I had a book on public policy, as I mentioned. Also launched last month – by our defence minister –was my film on our Armed Forces Medical Corps – it’s one of the oldest divisions in the world, going back 260 years. I’m working on a project on the Indian Constitution and a biopic on Amitabh Sen Gupta, the artist whose retrospective exhibition this year is organised by Artworld Chennai. My still photography project on the farmers crisis is also going on for the past 7-8 years.

All projects are joyous and offer their own challenges. It’s like bringing children into the world. You do the best you can, hope they’ll do well and go far, but you don’t know which one will. Regardless of their line of work you feel happy with each of them and what they achieve.

What is the future of Arriflex, Mitchell, Kodak Brownie? And that of Yashica, Nikon, Canon, Leica, Olympus…?

Some old camera brands like Konica and Minolta have merged, or evolved into digital Avatars like Arriflex. Others, like Kodak, have faded into history. Interestingly, a small Indian company has licensed their name to market TVs under Kodak brand name now. For those of us from the analogue generation, it’s a bittersweet feeling. When a beloved brand disappears, it feels like saying goodbye to an old friend. But such is the nature of change.

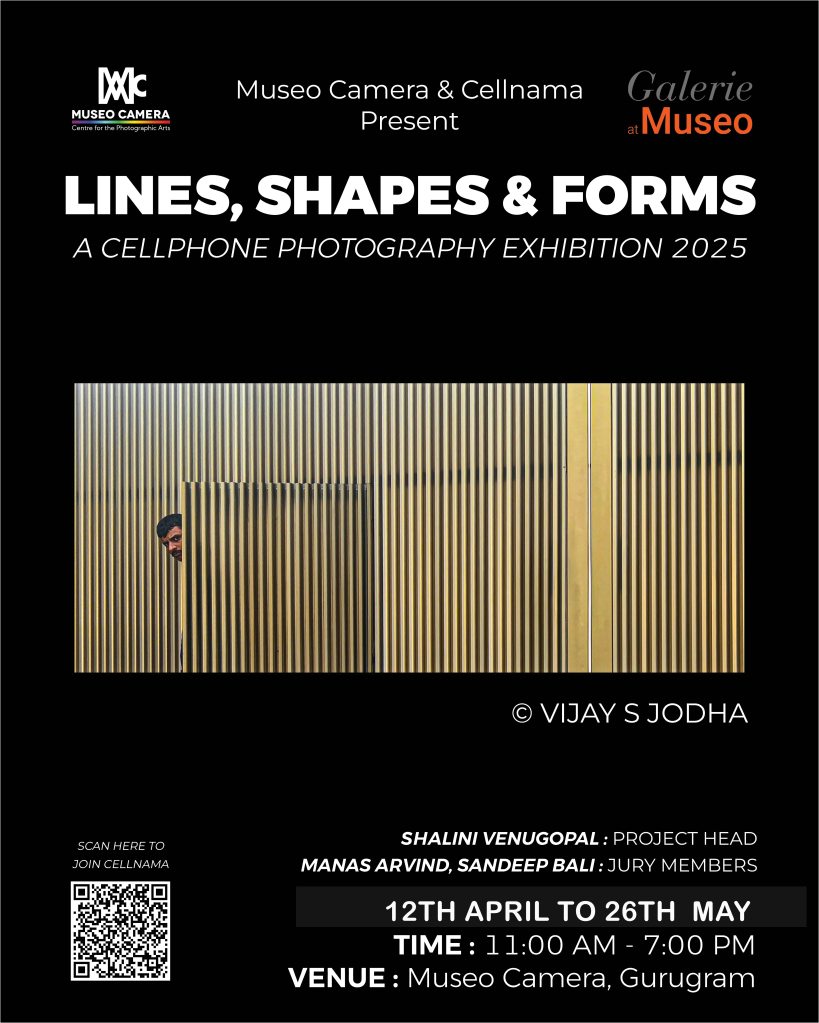

My friend Aditya Arya, one of India’s eminent photographers and a passionate camera collector, has created a remarkable space to preserve this legacy. He established the Museo Camera in Gurgaon, a non-profit centre promoting photographic art, which has become not only a camera museum but also a leading art and culture hub in the Delhi national capital region. If you’re an old time photographer passing through Delhi, it’s a wonderful place to revisit these “old friends.”

(Website of Museo Camera https://www.museocamera.org)

[1] University Grants Commission-Consortium for Educational Communication

[2] Robert Frank (1924-2019) was a photographer and documentary filmmaker.

[3] Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) was a humanist photographer, a master of candid photography, and an early user of 35mm film. One of the founding members of Magnum Photos in 1947, he pioneered the genre of street photography, and viewed photography as capturing a decisive moment.

[4] Three colours, published in 2005

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and writes books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International