By Paul Mirabile

1970s, Scotland

The three youngsters: Rachel, fourteen, her fifteen year old brother, Victor, both born in Edinburgh but raised in Moffat, Scotland, and Kenneth, sixteen, born in Moffat, were inseparable. After school or on week-ends they would explore all the surrounding forests and burr-filled heathers around their town. Victor, good at maps, chartered every trail twisting through, over and around the wooded hollows and hillsides of rowan, hazel, holly and hawthorn sloping up or down the cloven banks of the Annan River. Kenneth and Rachel, excellent artists, sketched all the cawing rooks, starlings and wild owls they espied perched in trees; all the weird insects they avoided crushing during their jaunts. Victor, also a fine artist, drew stags, wild boar, snakes and turtles which he observed at the foot of leafless trees or upon snow-packed hill-tops. They were quite an adventurous trio to say the least, unafraid of steep gorges or the trackless stretches of marshy woodlands.

Our tale opens on a warm spring day; a tale of artistic ardour, ingenious artifice, and especially childhood passions …

The entrance of the cave lay hidden behind a tangle of thorny bramble, thistle and snapdragons. Rachel was the first to discover it when from its mouth a swarm of swallows suddenly darted out, frightened no doubt by her approaching footsteps. Rachel advanced slowly, pushing aside thorny, arching thickets. She halted wide-eyed, staring at a narrow passage that slipped gently downwards deep into darkness.

“Kenneth … Victor, quick I’ve fund[1] a cave!” the excited girl cried, craning forward at its threshold. The boys, sleepy-eyed because they had been up with the larks, trudged towards the resounding shouts of their fellow explorer. They broke through the bramble and bush, joining Rachel at the mouth of the cave.

“Don’t go in,” warned Kenneth. “We have no torches and it may be a bear’s den.” Rachel, who had stepped into the passage, shuddered.

“Stop scaring her,” Victor snapped. “Da[2] said that a bear hasn’t been seen in this area since the 1920s.”

Kenneth raised his chin haughtily: “Perhaps … still, we need light to explore it.”

“Listen, tomorrow we’ll come back with torches, pokes[3], bits[4] and paper to make a map of it,” Rachel suggested sagely.

“A map of what?” asked her brother, poking his head into the cavernous umbers.

“Of our cave, laddie, what do you think? It may be full of treasure?”

“Gold … diamonds … rubies …?” asked Kenneth with sarcasm, giggling under his breath.

“Aye! Aladdin’s cavern,” echoed Victor quite seriously. “Let’s get back and make all the preparations.” The three jubilant explorers did exactly that after having zig-zagged through the patches of fabled forest and heather fields that girted their town.

They spent that evening readying their equipment: sandwiches stuffed into knapsacks, boots, torches, pocket-knives, pencils, paper and rope, if needed. Nothing was to be said about the cave to their parents. It was their secret, and their secret alone …

It was in the wee hours of a Saturday morning after a speedy breakfast that they penetrated the mouth of the cave, heedful of anything alive, wary of anything dead. Not once did they have to stoop. Training their torches on the walls, the youngsters at first walked down a long, narrow gallery whose walls glistened smooth like obsidian, yet brittle to the touch. Then the gallery suddenly widened into a huge chamber.

“It’s like a kirk[5],” whispered Kennth, almost with reverence.

“How do you mean?” whispered Victor in turn.

“Well … look, we’re standing in the nave, and there, further back is the apse.”

Victor stared in awe. The chamber indeed bulged out in colossal dimensions; it did have a church-like configuration.

“Here … Here!” Rachel gesticulated in a hushed voice as if not to disturb anything … or anyone ! “It’s a well.” She stepped back. Victor and Kennth rushed over, stopping at the edge of a huge opening in the rocky floor. Kenneth picked up a pebble and tossed it down. Down and down and down it floated: soundlessly …

The children stared at one another somewhat put off. They walked cautiously back into the ‘kirk’ chamber.

Rachel stopped, scanning the walls: “I have an idea, laddies.” She paused to create a suspenseful sensation, a whimsical smile highlighting her bright, round eyes. “Why don’t we decorate the walls of the cave with animals … or hunters just like the cavemen artists did in their caves ? I’m first in my class in art and so is Kenneth. Victor, too, paints marvellously well.” The two boys eyed her curiously.

“But why would we want to do that?” Kenneth enquired superciliously, although intrigued by Rachel’s idea, for indeed Kenneth had proven himself the best artist at their school.

Rachel trained her torch on the walls then argued: “First, to practice our painting, right ? Then … then … to play a joke on everyone in town about their origins.” Rachel’s eyes glowed with mischievousness.

“What do you mean play a joke on everyone in town?” It was now Victor who sized up his sister suspiciously.

“We could tell everyone that we ‘fund‘ cave paintings and have our pictures in the dailies.” Rachel was absolutely radiate with rapture.

Kenneth laughed. Victor appeared to warm to the idea, albeit prudently. He paced the cavern floor, scanning the smooth, dry walls. He spun on his heels and faced an adamant Kenneth, who scrutinized both with a cool aloofness: “Aye! What a bloody good idea! It’ll be our project, a real artistic project; and who gives a damn if people are fooled or not. Don’t you see Kenneth, it’ll be a brilliant chance to paint what we want to paint.”

Kenneth passed his hand carefully along the cave walls, his finger-tips tracing imaginary designs. He chuckled: “Brilliant idea, Rachel,” he admitted. “Aye, a stroke of inspiration! We can ground and sift our own pigments with the forest and riverside plants and minerals just like the cavemen did. The rock isn’t granite, look, it just chips away when you scratch it. First we’ll engrave the pictures then paint them. It’ll fill the cave with a magical lustre, a true primitive or prehistoric aura.”

“We could steam vegetables and use the juice to paint,” added Victor, growing more inflamed.

“We could even mix the paintings with hot wax for a more aged effect,” Rachel suggested.

“Nae! That’s how the Greeks painted. That technique is called encaustic. We want a caveman’s artistic technique and touch,” Kenneth checked her.

“But won’t we be going against the law?” Victor asked in a subdued tone.

“Don’t be a dafty, of course not!” Rachel reprimanded him. “It’s our cave. We fund it, didn’t we ? We’re only decorating it.”

“Aye. But to play a trick on adults,” he continued lamely.

“A little trick won’t have us tossed into gaol, laddie,” reminded Kenneth. “It’s a swell idea, and we can really explore our painting techniques and colour schemes.”

And so in the depths of that cave, unknown to the rest of the world, the youngsters’ project, or should I say, scheme, had been sealed.

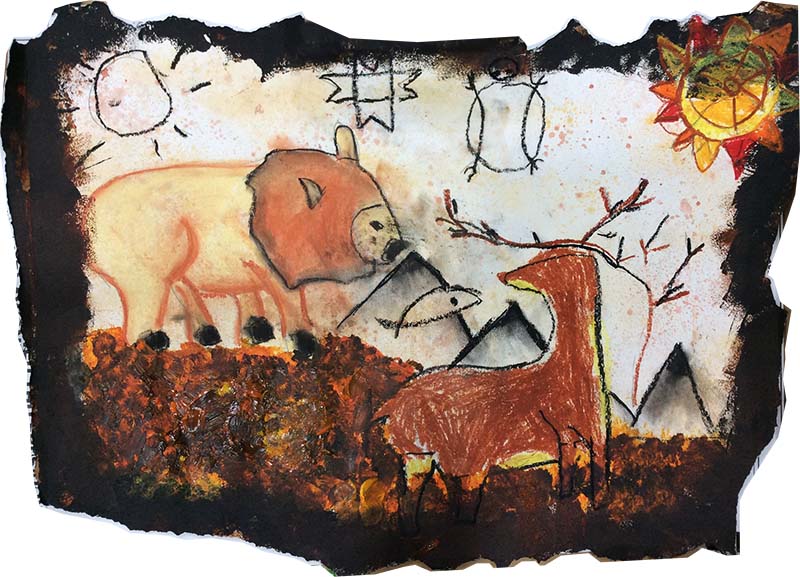

Hence, the cave became their point of reference, their realm of eternal childhood, more intimate than either school or home, their retreat of borderless imagination. Day after day on those barren walls within the dry darkness of their grotto-world, their imagination, so fertile because bubbling over with youthful turbulence, brought to life animal figures, first hewn with small chisels then painted with fingers (especially thumbs), or with sticks, brushed over with clumps of grass. No paint-brush was ever used. Their painting techniques remained those of prehistoric cave-artists.

Kenneth, well versed in rock painting from his school art classes and own research, chose the designs and advised Victor and Rachel how to apply the pigments. Each chose a section of the cavern to exercise his or her talents: Victor began to draw several cattle heads in the kirk with umbers that he ground and sifted from clay, boiled acorns, with their cups, and boiled mushrooms. It conferred to his cattle grey, tawny tones; tones that seemed to afford a glow of warmth to the cold walls.

Kenneth took charge of the western nave of the kirk, animating its walls with a big black cow, two galloping horses and two bison, all in charcoal black with a fringe of madder pigment. The plant had been gathered at the Annan riverside, then ground and sifted into a deep, crimson red.

As to Rachel, she applied her talent on the eastern nave wall with a two-metre long frieze of deer heads. Rachel also took charge of making a small fire to boil the plants and vegetables, whose steamed-juice transformed the plants or vegetables into liquid pigments. She poured the liquid into small glass containers and let them sit for one night before application.

“We’re like the cavemen who discovered fire,” Rachel said cheerfully as she steamed the plants and vegetables she had gleaned either from the forest or ‘borrowed’ from her mother’s kitchen.

“Not so, lassie. It was light that discovered fire, the cavemen merely rendered it physical,” corrected Kenneth smugly. Rachel shrugged her shoulders …

With his customary pedantry, Kenneth advised: “Don’t forget mates, painting doesn’t reproduce what is visible, but restores or renders what no one has ever seen.”

Rachel and Victor ignored him, chuckling to themselves.

They worked diligently in rhythm with the stillness of the cave, their imaginations soaring to the height and breadth of their lithic horizon. For they were careful not to surpass those limits, not to crowd the walls with too many figures. The roaming animals needed space to breathe and the young artists provided them with that vital space: horses trot … cows graze … deer gambol. Kenneth, after having examined a hunter armed with a bow in a book of cave paintings, added this figure to his zoological repertoire. The hunter had let fly an arrow and followed its flight towards something unknown. Kenneth had his arrow fly towards one of his elks. The posture of the hunter having released his arrow from a taunt bow was crudely traced then coloured in rusty ochre. It would be the only human representation of the grotto paintings.

All the paintings had been previously drawn on a flat surface of paper by Victor. Rachel arranged the positions of their depictions and the boys made mental notes of them before undertaking the actual wall representation. Kenneth had reminded Rachel and Victor that the intention of the artist was not to copy what they see but to express it, and that their undertaking should not seek a tawdry or fantastic effect, but a simple one, for simplicity is essential to true art. If they really hoped to convince the townsfolk of the millennial authenticity of their pictures, then this artistic canon had to be respected scrupulously.

Gradually the cave walls burst out into a magical menagerie: Victor’s two-horned aurochs, painted in umber came to life and Rachel’s deer-head frieze boldly gambolled out of the rock in striking shades of madder red. Rachel, applying a prehistoric technique, blew the madder pigment on to the wall through a straw, then smeared it roughly with her thumb or a feather.

The volume of their art thickened with vegetal and mineral glints as the volume of the walls, too, thickened with a phantasmagoria creatures depicted in a style they thought of as from stone ages.

Sometimes, the youngsters would dance and sing round the fire, recite poetry, or even compose a few verses of their own in joyful wantonness. “Our cave is the setting of an unfolding story, laddies,” Rachel giggled.

This pictural setting was indeed the fruit of their childhood imagination … and talent.

The day finally arrived when the cave-artists put the final touches to their masterpiece, an œuvre of considerable talent, even genius, given the lack of adult counsel and absence of light in the cave. For they had laboured as the prehistoric artist had laboured: by torch light (theirs, of course, electric!), and from the flames of their little fire’s chiaroscuro dancing upon the walls.

This being said, to divulge the discovery of the cave and its pictural contents would be a bit dodgy. They chose to wait several weeks to reflect on how they would announce their discovery. Kenneth, meanwhile, every now and then tossed dust on the pictures to harden and ‘age’ them. They lost their glint but the umbers seemed to strike the eye more prominently. They left nothing in the cave that would jeopardise their scheme. The ashes of their fire were swept into the well or used to tinge some of the figures in a rough, taupe grey.

Finally, on a clammy late Saturday morning, Rachel and Victor stormed into their parents’ home out of breath :

“Maw! Da! Come quick,” exclaimed Rachel red in the face. “We fund a cave.”

“Aye, a real deep cave full of animal pictures,” seconded Victor, sweating from the brow, either from exhaustion or fear. “You have to come to see for yourselves,” he insisted. “The cave’s not far off, near the riverside.”

Their mother and father, not very eager to tear themselves away from their armchair reading, nevertheless let their panting children drag them to the mouth of the cave. Once there, they all entered, the parents a bit warily. Victor, at the head of the expedition, led them down into the cave, scanning the walls with his torchlight which exposed several paintings. His father, unversed in cave-paintings, had, however, studied art at university in Edinburgh. The paintings intrigued him. His wife stood dumbfounded before such a vast array of art work.

“What striking pictures!” she exclaimed, staring wide-eyed in admiration as her husband illumined one section of the wall after another. Bedazzled by such parental compliments, Rachel felt an ardent urge to thank them. She checked herself. Victor remained quiet.

“Aye!” uttered their father reflectively. “This is certainly not a chambered cairn tomb. I’ll contact specialists immediately. Meanwhile, you two (indicating his children) get the school authorities to photograph the cave and the paintings. Even if they’re not authentic, they do make for a good story in the local papers until the police find the culprits who contrived this whole thing.”

“What do you mean not authentic?” asked Victor timorously.

“Well, you know, there have been art counterfeiters over the ages, but it takes time before the experts uncover their ingenious device.”

“What happens to them?” Rachel dared ask, eyeing Victor sullenly.

“They’re tossed into gaol where they rightly belong!” concluded their father, puckering his lips. Rachel winced at the word gaol …

When their parents had returned home, Rachel and Victor made a bee-line for Kenneth’s house, where they informed him of their parents’ reaction, especially the tossing into gaol.

Kenneth chuckled out of the corner of his mouth: “Keech[6] ! Minors aren’t thrown into gaol, goonies[7]. Nae, you know what they say: ‘Fools look to tomorrow. Wise men use tonight.’” Neither Rachel nor her brother really understood that point, but it did have a pleasant ring to their ears.

The following weeks were hectic ones for the youngsters both at home and at school. Pupils bombarded them with questions whilst at home the telephone never stopped ringing. All the thorny bramble, thistle and snapdragons had been cut away from the mouth of the cave allowing photographers to take pictures and journalists to examine the figures for themselves. Soon travellers from afar reached the cave to feast their eyes on these wonderful works of prehistoric art. During that feverish time no one dreamed that they had been drawn by our three adventurers …

Secretly the adventurers were delighted. And for good reason: they had their pictures taken in front of the cave by professional photographers, and had been interviewed not only by local reporters, but reporters sent from Edinburgh, Glasglow and even London. Experts had been contacted, seven to be exact, two of whom from London.

Kenneth brooded over the outcome. He sensed that the arrival of the experts bode ill-tidings. He knew they wouldn’t go to gaol, but, would they query of the age of the pigments however primitive their mixtures, their application and original whereabouts? Would they suspect foul play simply because, besides carved stone balls, prehistoric art work had never been discovered in Scotland? These men had very technical means to detect the precise date of pigments and their wall application …

All seven arrived together. Together they entered the cave brandishing large, powerful torches and miners’ helmets. Huge crowds had gathered for the occasion: photographers, journalists and even local writers swarmed throughout the surrounding hilly forests. Kenneth sat on a rock, his chin cupped in his hands. He felt miserable. Victor, wringing his hands frantically, paced back and forth near the riverside until his footfalls had traced a path. Rachel bit the ends of her hair nervously, casting furtive glances towards the thickening crowd. Dozens of people had been congratulating them on their find all morning.

“Would they congratulate us as much if they learned we were the artists?” snickered Victor sarcastically.

“Aye, I wonder,” Rachel responded drily.

“Bloody hell, why make things worse!” Kenneth snorted stiffly, staring at the backs of the crowd in front of the cave. “The whole thing was zany[8] to begin with. Those professors will be on to us, I’m sure.” All the three bowed their heads resigned to their fate in silent expectation.

The seven filed out of the cave with wry smiles difficult to decipher. A strange composition indeed: severe or cryptic … sharp or ironic … gruff or awe-inspired! No one appeared to be able to interpret those ambivalent smiles, especially our three young artists, who had by then stomped up the humpy hillside towards the murmuring crowd. Everyone present eyed the children in nervous anticipation as if they held the key to unlock those facial mysteries. Alas none had …

The experts pushed through the crowd and reached the standing children. One of them with a pointy beard and a sweet smile asked them very politely to lead them to the home of their parents where they would like to speak to them in private. Kenneth’s father ran up and immediately agreed to offer his home for their conference. Besides, it was the closest. He led the way through the fabled forest and over the heather fields. Arriving at the door, the pointy bearded expert informed Kenneth’s father that their conference was be held without parental intrusion. Had the father any choice ? Apparently not, for the front door of his humble home was shut quietly in his astonished face …

Now whatever took place behind the shut door of that humble home the ever-present narrator is, alas, at a loss to relate. For hours and hours and hours seemed to pass, and having reached the number of words permitted in this tale, it behoves him to abandon his readers to imagine the outcome … or the verdict themselves …

[1] ‘found’ in the Scots tongue.

[2] ‘Father’ in the Scots tongue.

[3] ‘bag or pouch’ in the Scots tongue.

[4] ‘Boots’ in the Scots tongue.

[5] ‘Church’ in the Scots tongue.

[6] ‘Rubbish’ in the Scots tongue.

[7] ‘Idiots’ in the Scots tongue.

[8] ‘Crazy’ in the Scots tongue.

Paul Mirabile is a retired professor of philology now living in France. He has published mostly academic works centred on philology, history, pedagogy and religion. He has also published stories of his travels throughout Asia, where he spent thirty years.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International