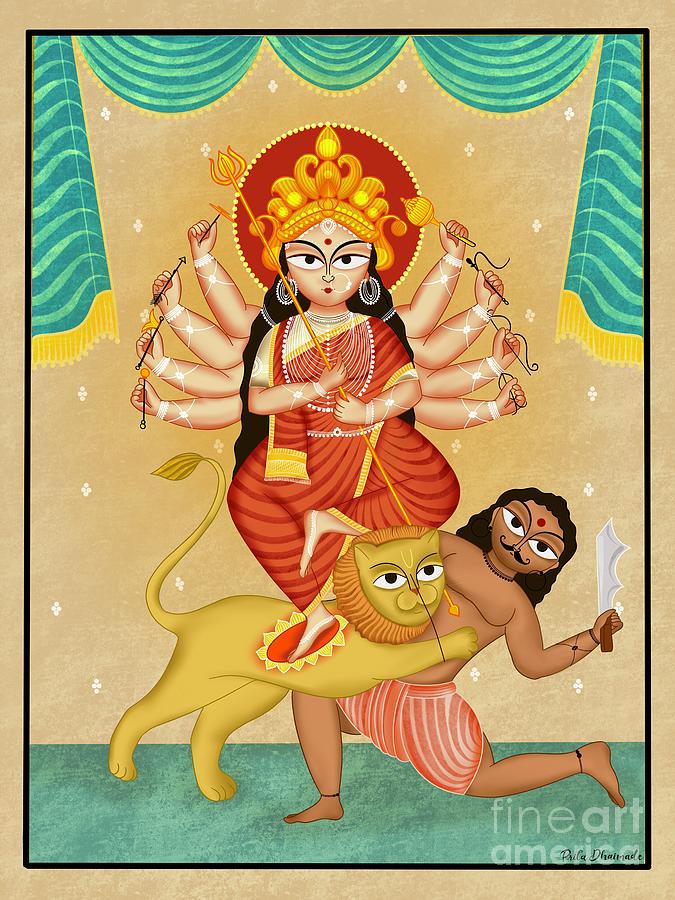

Long ago as children, we looked forward to the autumnal festival of Durga Puja. For those who lived outside Bengal, there was no holiday but it was still a break, a season filled with joie de vivre, when family and friends would gather to celebrate the community-based festival, Durga Puja. Parallelly, many from diverse Indian cultures celebrated Navratri — also to do with Durga. On the last day of the Durga Puja, when the Goddess is said to head home, North Indians and Nepalese and some in Myanmar celebrate Dusshera or Dashain, marking the victory of Rama over Ravana, a victory he achieved by praying to the same Goddess. Perhaps, myriads of festivals bloom in this season as grains would have been harvested and people would have had the leisure to celebrate.

Over time, Durga Puja continues as important as Christmas for Bengalis worldwide, though it evolved only a few centuries ago. For the diaspora, this festival, declared “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity” by UNESCO, is a source of joy. While devotees welcome the Goddess Durga and her children home, sons and daughters living away would use this event as a reason to visit their parents. Often, special journals featuring writings of greats, like Satyajit Ray, Tagore, Syed Mujtaba Ali, Nazrul would be circulated in the spirit of the festival.

The story around the festival gives out that like an immigrant, the married Goddess who lived with her husband, Shiva, would visit her parent’s home for five days. Her advent was called Agomoni. Aruna Chakravarti contends in her essay, Durga’s Agomoni “is an expression, pure and simple, of the everyday life of women in a rural community –their joys and sorrows; hopes and fears”. While some war and kill in the name of religion, as in the recent Middle Eastern conflict, Chakravarti, has given us an essay which shows how folk festivities in Bengal revelled in syncretism. Their origins were more primal than defined by the tenets of organised religion. And people celebrated the occasion together despite differences in beliefs, enjoying — sometimes even traveling. In that spirit, Somdatta Mandal has brought us travel writings by Tagore laced with humour. The spirit continues to be rekindled by writings of Tagore’s student, Syed Mujtaba Ali, and an interview with his translator, Nazes Afroz.

We start this special edition with translations of two writers who continue to be part of the syncretic celebrations beyond their lives, Tagore and Nazrul. Professor Fakrul Alam brings to us the theme of homecoming explored by Nazrul and Tagore describes the spirit that colours this mellow season of Autumn

Poetry

Nazrul’s Kon Kule Aaj Bhirlo Tori ( On which shore has my boat moored today?), translated from Bengali by Professor Fakrul Alam, explores the theme of spiritual homecoming . Click here to read.

Tagore’s Amra Bedhechhi Kasher Guchho (We have Tied Bunches of Kash), translated from Bengali by Mitali Chakravarty, is a hymn to the spirit of autumn which heralds the festival of Durga Puja. Click here to read.

Prose

In The Oral Traditions of Bengal: Story and Song, Aruna Chakravarti describes the syncretic culture of Bengal through its folk music and oral traditions. Click here to read.

Somdatta Mandal translates from Bengali Travels & Holidays: Humour from Rabindranath. Both the essay and letters are around travel, a favourite past time among Bengalis, especially during this festival. Click here to read.

An excerpt of In a Land Far From Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan by Syed Mujtaba Ali, translated by Nazes Afroz. Click here to read.

Interview

A conversation with Nazes Afroz, former BBC editor, along with a brief introduction to his new translations of Syed Mujtaba Ali’s Tales of a Voyager (Jolay Dangay). Click here to read.