Editorial

Finding Godot?… Click here to read.

Conversations

Ratnottama Sengupta talks to Ruchira Gupta, activist for global fight against human trafficking, about her work and introduces her novel, I Kick and I Fly. Click here to read.

A conversation with Ratna Magotra, a doctor who took cardiac care to the underprivileged and an introduction to her autobiography, Whispers of the Heart: Not Just a Surgeon. Click here to read.

Translations

Two poems by Nazrul have been translated from Bengali by Niaz Zaman. Click here to read.

Masud Khan’s poetry has been translated by Fakrul Alam. Click here to read.

The White Lady by Atta Shad has been translated from Balochi by Fazal Baloch. Click here to read.

Sparrows by Ihlwha Choi has been translated from Korean by the poet himself. Click here to read.

Tagore’s Dhoola Mandir or Temple of Dust has been translated from Bengali by Mitali Chakravarty. Click here to read.

Pandies Corner

Songs of Freedom: What are the Options? is an autobiographical narrative by Jyoti Kaur, translated from Hindustani by Lourdes M Supriya. These narrations highlight the ongoing struggle against debilitating rigid boundaries drawn by societal norms, with the support from organisations like Shaktishalini and pandies’. Click here to read.

Poetry

Click on the names to read the poems

Rhys Hughes, Maithreyi Karnoor, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal, Sivakami Velliangiri, Wendy Jean MacLean, Pramod Rastogi, Stuart McFarlean, Afrida Lubaba Khan, George Freek, Saranyan BV, Ryan Quinn Flanagan, Sanjay C Kuttan, Peter Magliocco, Sushant Thapa, Michael R Burch

Poets, Poetry & Rhys Hughes

In City Life: Samples, Rhys Hughes takes on the voice of cities. Click here to read.

Musings/Slices from Life

Ratnottama Sengupta Reminisces on Filmmaker Mrinal Sen

Ratnottama Sengupta travels back to her childhood wonderland where she witnessed what we regard as Indian film history being created. Click here to read.

Snigdha Agrawal gives us a slice of nostalgia. Click here to read.

Healing Intellectual Disabilities

Meenakshi Pawha browses on a book that deals with lived experiences of dealing with intellectual disabilities. Click here to read.

Musings of a Copywriter

In Hobbies of Choice, Devraj Singh Kalsi explores a variety of extra curriculums. Click here to read.

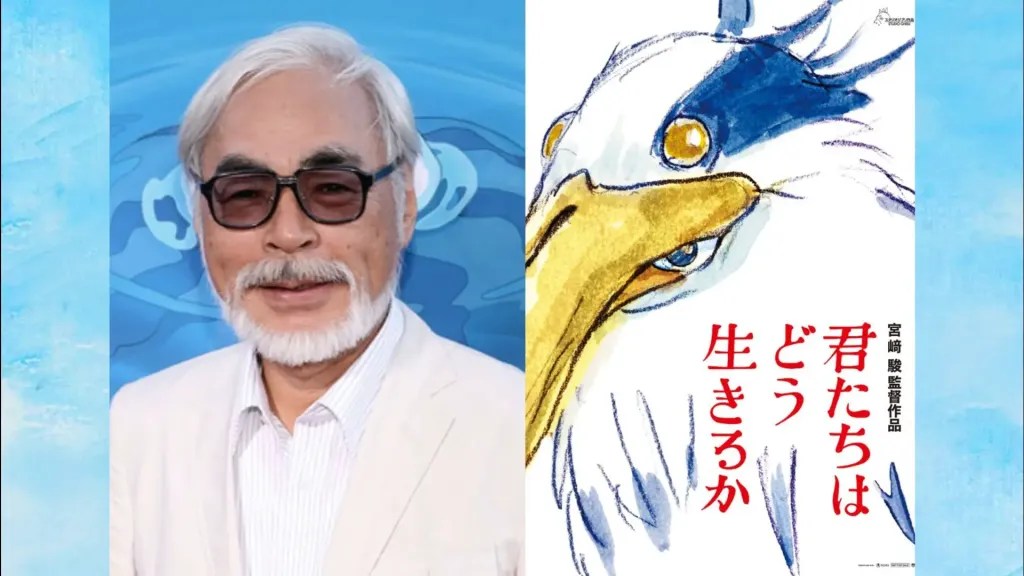

Notes from Japan

In Becoming a Swiftie in my Fifties, Suzanne Kamata takes us to a Taylor Swift concert in Tokyo. Click here to read.

Essays

Sohana Manzoor takes us around the historic town. Click here to read.

Aditi Yadav explores the universal appeal of the translation of a 1937 Japanese novel that recently came to limelight as it’s rendition on the screen won the Golden Globe Best Animated Feature Film award (2024). Click here to read.

The Magic Dragon: Cycling for Peace

Keith Lyons writes of a man who cycled for peace in a conflict ridden world. Click here to read.

Stories

Paul Mirabile tells a strange tale set in Montana. Click here to read.

Apurba Biswas explores a futuristic scenario. Click here to read.

Ravi Shankar gives a story about immigrants. Click here to read.

Ravi Prakash writes about life in an Indo-Nepal border village. Click here to read.

Neeman Sobhan gives a story exploring the impact of the politics of national language on common people. Click here to read.

Book Excerpts

An excerpt from Nabendu Ghosh’s Journey of a Lonesome Boat( Eka Naukar Jatri), translated from Bengali by Ratnottama Sengupta. Click here to read.

An excerpt from Upamanyu Chatterjee’s Lorenzo Searches for the Meaning of Life. Click here to read.

Book Reviews

Somdatta Mandal reviews The History Teacher of Lahore: A Novel by Tahira Naqvi. Click here to review.

Basudhara Roy reviews Srijato’s A House of Rain and Snow, translated from Bengali by Maharghya Chakraborty. Click here to read.

Bhaskar Parichha reviews Toby Walsh’s Faking It : Artificial Intelligence In a Human World. Click here to read.

.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International