A brief overview of Rajat Chaudhuri’s Spellcasters, published by Niyogi Books, and a conversation with the author.

Spellcasters by Rajat Chaudhuri is a spellbinding fast paced adventure in a phantasmagorical world against the backdrop of climate change and environmental disasters. Chaudhuri, a proponent of solarpunk[1], has nine books under his belt, including the Butterfly Effect (2018) a few fellowships (like Charles Wallace), and a sense of fun as the characters hurtle through the book gripping the readers with their intensity.

In this novel, Chaudhuri’s universe is run by a council, based on Akbar’s Navratnas[2]. They seem to be people in charge of running a chaotic world. This group — though not drawn from Akbar’s court but from various parts of the world — are known as the ‘Nine Unknown Men’. They are said to host great people from the past in another dimension. As they “fold the dimensions and transform matter from one form to another”, manipulating and yet healing characters like Chanchal Mitra, his protagonist, putting the world to ‘rights’ by destroying villainous capitalists who sport shrunken heads of their enemies and indulge in creating drugs that can lead to annihilation of humankind, there is a fine vein of coherence which gives credibility to Chaudhuri’s imagined world.

The locales are all fictitious but highlight real world problems of climate change, unethical scientific research and uncontrolled economic growth that only pamper the pockets of the rich craving power. He weaves in episodes that had made headlines in Indian media, like Ganesha drinking milk, and Himalayan disasters, a result of interferences by human constructs like dam building and ‘development’. A sensuous mysterious woman with curly hair, Sujata, who sets Mitra back on track and is as good as a Marvel heroine when accosted with villains, adds to the appeal of the book.

He describes a barefoot tribe which seems more idyllic than real. But given that it is a phantasmagorical fantastical novel, one would just accept that as a part of the Spellcasters’ world. However, the import of the message the tribal leader conveys to the characters on the run is astute. “We take little from this land and try to return what it gives us. So did our forefathers and all those who walk this country with the animals. But the settlers in villages and cities never tire of drawing out the last drop of earth’s riches…” A similar take on nomadism and settler communities can be found in nonfiction in Anthony Sattin’s Nomads: The Wanderers Who Shaped our World, who talks of the spirit of brotherhood, or asabiyya, that bound the nomads together, a concept borne in the fourteenth century in the Middle East. One wonders if the Nine Unknown Men who cast spells are also bound by some such law as at the end the ‘Perfect Lovers’ disappear into another adventure in time… perhaps, to resurface in Chaudhuri’s next book?

Chaudhuri is poetic with words. He writes stunning descriptions of storms and climate events: “The rivers are boisterous and overflowing, the skies are being torn apart by forests of lightning. The great snow-capped peaks from where these rivers emerge have vanished behind walls of water tumbling down from the skies.”

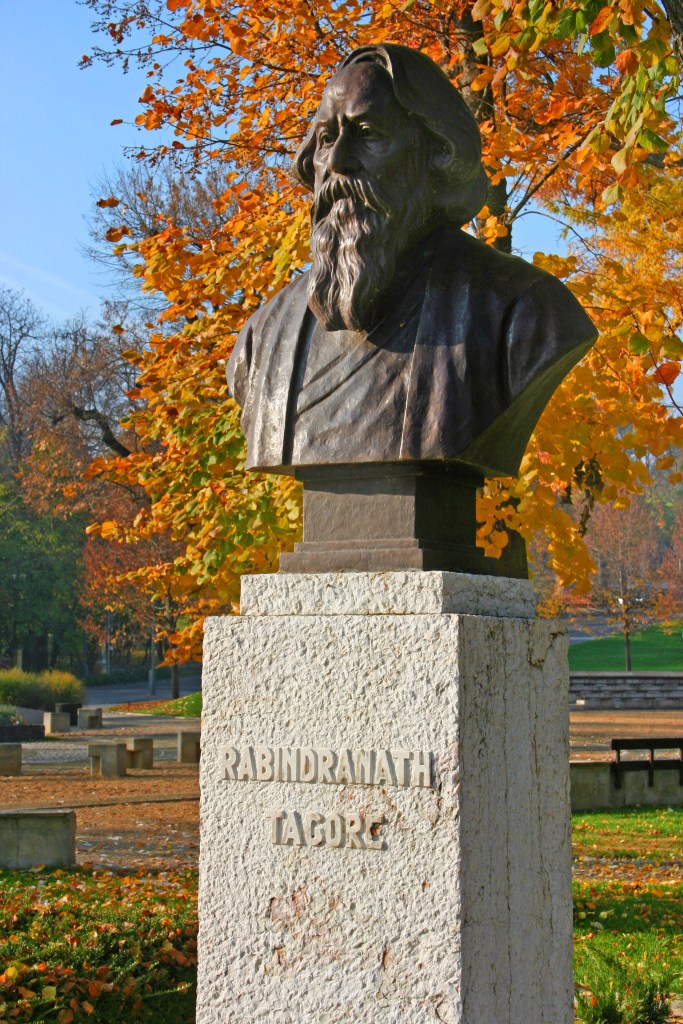

The thing that makes his book truly unique is the way his characters seem to internalise or grow out of the miasma that encapsulates the world below the mountains. They seem like an extension of the chaotic external environment with strange happenings. Even in the council meeting held by the Nine Unknown Men, some of the crowd seem to be wisps of mists. Chanchal Mitra has to go above the hovering fog to start healing back to normal. The novel starts in a seemingly dystopian setting. The ending is more of a fantasy. There is a strain of Bengaliness in his wry humour, in small factual details, like we find Jagadish Chandra Bose seated in the council hall, though LJ drawn from RL Stevensons’ fictional pirate from Treasure Island (1883), Long John Silver, and Caligari from The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920), have larger and more crucial roles in the novel. Spellcasters is a thriller that entices with words, a gripping plot and suspense — set against a backdrop of strange climate events that are becoming a reality in today’s world, though the characters are more interesting than those drawn from real life.

The novel is written by an author who is compelled by perhaps more than a need to record his times. He has a vision… though not clearly laid out as a didactic message. But it hovers in the fog that is part of the book. One of the things that came across[3] was to create utopia, we need the chaos of dystopian existence…a theme that rebel poet Nazrul addresses in his poem, ‘Proloyullash’ (The Frenzy of destruction): “Why fear destruction? It’s the gateway to creation!”

In a past life, Chaudhuri had been a consumer rights activist, an economic and political affairs officer with a Japanese Mission and a climate change advocate at the United Nations, New York. Working in such capacities could have generated his vision, his worldview. Let us find out more about it by asking him directly:

What made you turn to writing from being an activist and climate change advocate? How long have you been writing fiction? What made you turn to fiction?

I am still involved with activism through my work with NGOs and my writing for popular media and other venues. However, I have gradually shifted my energies to creative fiction through which, nowadays, I try to engage with climate change and other planetary crises.

I have been writing fiction for nearly two decades now, my first novel, Amber Dusk was published seventeen years ago. As a full-time activist I have had the opportunity to interact and work with people from various strata of society right from the villages of India to international fora like the United Nations, where I have often noticed a tug-of-war of ideas between big business, sections of civil society, governments and other major groups like women, indigenous people and so on. While watching and participating in these, I had begun to realise how stories can open another flank in our efforts to communicate our ideas.

Today, you see, storytelling is everywhere. Stories are being recruited for issues big or small, important or completely worthless, even dangerous! In my case, I realised that stories can be an important vehicle for communicating issues surrounding planetary crises to my audience. Stories tend to be sticky — they remain with us for a long time and studies are now showing that well told stories can trigger changes in perceptions, beliefs and ideas. But it took me a long time to transform this realisation into book projects. Before that I had written other books – contemporary fiction, urban fantasy and so on.

What made you conceive Spellcasters? How long did it take you to write?

There are two or three strands that came together in the writing of Spellcasters. Most important among these is my interest in psychology and mental disorders and specifically in the fact that the ideas that dominate the world today, you can call them spells too, make us behave like we are affected by some kind of mental illness. Ideas and practices like limitless growth, conspicuous consumption and so on, make us behave as if we have lost our minds as we go on plundering the planet for energy and resources despite the fact that `nature’ is striking back at us with ever-increasing fury. So, our mental illness is causing planetary illness and at the centre of all this are these powerful, mesmerising, false beliefs, which right from the time of the Club of Rome have been known to be dangerous.

So, when I began to plan this novel, all these thoughts were in my mind partly driven by my activism. And at the same time, I had been reading Sudhir Kakar’s works about magic and mysticism in India and the parallels between Indian and western psychology so all of that came together. It took me about five years to complete Spellcasters not at one go, there was other stuff I have worked on in between.

What kind of research went into making the book?

To create the main character, the journalist Chanchal Mitra, I worked closely with my psychoanalyst friend Anurag Mishra who happens to be a student of Sudhir Kakar. And that research was really intense. We had long face-to-face and online sessions and I read a lot about the varieties and specificities of mental disorder.

Then there is of course that background layer of interest which oftenseeds ideas in your mind. This usually comes from your reading, and I had been interested in reading about the occult traditions of the East and the West for many years. Characters like Mme Alexandra David-Neel[4], the magic healers among indigenous peoples, the power of entheogenic substances like mushrooms have always fascinated me, and some of that came back while researching this book. Writing the climate layer of the story was comparatively easier because of my first-hand activist experience.

Do you have a vision or a message that you tried to address in this novel? I felt it moved from a dystopian setting to that of a fantasy — though not to utopia. Do you think a dystopian vision is necessary to evolve utopia?

The message is simple, and we all know it: Ideas of limitless growth have affected us mentally and so we behave and act in ways (resource extraction, carbon emission) that are making the planet sick. We are passing on our illness to the planet. The belief in limitless growth is a zoonotic disease that our species has transferred to the living planet. Still, we do not act because we are under the effect of these powerful ideas, these powerful spells, that’s where the novel gets its name. The message, if we can call it one, is to be aware of this and try to break out of these spells.

The path to utopia is not necessarily through dystopia. We can start hoping and acting today before things get really bad. Which is the locus of the whole solarpunk movement with which I am closely associated as an editor and creator. But `darkness’ can be redeeming too. Jem Bendell writes about this in detail. Grief and sorrow can indeed make us stronger; author Liz Jensen navigates grief and encounters hope in Your Wild and Precious Life, which is a must read for everyone asking these questions. But coming back to Spellcasters it is really neither dystopia or utopia if we are talking about the climate layer of the story, it’s very much set in the present. What might look dystopian are the gothic and magical elements and settings which serve as a counterpoint to the cold logic of the scientist character, Vincent.

Your novel has broken various barriers by mingling different constructs. So, tell us, how do you combine realism with fantasy, science with literature and create your own world?

It’s not difficult actually. Fantasy, magic and `unreason’ are woven around the borders of the familiar. We see them often without noticing it. Leaping a little higher or using a prescription eye-cleanser can do the trick!

To answer the other part of your question, science and literature or nature and culture were never apart in the first place. They were sundered because of the partitioning project of modernity which goes back to the work of Hobbes and Boyle and has its own history and protagonists. Science fiction as you know does not care much for this division. Climate fiction because of its scaffolding of science and reason needs to bring the two together. As a climate fiction writer, I try to keep the scientific complexities in the background, but they remain as building blocks of the story. In this book however we have a full chapter which is out of a scientist’s journal, and I did that for a change in flavour and in the spirit of experimentation.

Are your imaginary locales based on real cities? Please elaborate.

Often so. In Spellcasters the cities of Anantanagar and Aukatabadare modelled on Calcutta and Delhi respectively. A close reader can easily pick out the similarities but then I also enjoy changing some details especially when I am writing mixed-genre work like this one. So, there is no Chinese joint (like the one Chanchal hangs out at) in Calcutta where you can openly smoke weed but there are places quite similar to the one I described and there is indeed a real person with an eye of glass who used to hang out in one of these.

You have spoken of storms on the hills. Do you also see this as an impact of climate change? Do you think building roads, tunnels or hydel power stations on the hills can, over a period of time, have adverse effects on climate or humanity? Can you suggest an alternative to such ‘development’?

The avalanches, the unseasonal rains, especially the cloudbursts are all closely connected to climate change. Having said that, we also have to be careful to avoid climate reductionism. Often it is a concatenation of factors (including carbon emissions and climate change) and processes, their effects amplified by feedback loops, that precipitate disasters. This is very true if we study migration, for which climate change can be one of the driving forces but there could be other factors like economic opportunities, cultural patterns etc implicated in such flows.

Mindless development which does not take into account the fragility of nature and the interconnections between all beings big and small, microscopic or enormous, animate or inanimate, will set into motion processes that will precipitate crises like climate change. Yes, big dams are definitely a problem and small hydro is always a better option. We often hear that nature is self-healing or that there have been many previous extinctions, and that the planet has made and remade itself, but that’s like telling ourselves, please prepare for suicide while the super-rich and the cults of preppers, especially in the advanced industrialised nations, can escape to their doomsday bunkers.

The alternatives to the current development model is to be found in the ideas of Gandhi, of Schumacher, in solarpunk literature, in Vandana Shiva’s works among plenty of other places. The basic idea is to live in harmony with the planet, cut down on emissions, reduce resource extraction, try community based participatory solutions to problems instead of relying on economic, high-tech or market-based instruments, step back, go slow and let nature cloth and feed us so that we can live with dignity while forsaking greed.

In Spellcasters, you show climate change as an accepted way of life at the end. Do you think that can be a reality? Do you think climate change can be reversed?

A novel often presents itself as a bouquet of ideas without the author demonstrating any clear bias for one over the others. But as an activist-writer I usually drop clear hints as to what is more desirable without making it too obvious. There is always this ongoing duel between politics and aesthetics in a novel and the best among us balance the two quite well.

Climate change can of course be engaged with, controlled and reversed, if we can stick to the ambitious targets of the Paris climate agreement with the rich nations facilitating the process with more funds to poorer nations. Both producers and consumers have a role to play here, and we need serious lifestyle changes in the advanced industrial nations (or rather the global North) and a serious focus on climate justice for any meaningful change to occur. Only planting trees and carbon-trading won’t do.

Your language is very poetic. Do you have any intention of trying poetry as a genre?

Thank you. I haven’t ever thought of writing poetry because I am not gifted with the art of brevity which I think is essential there. But I have enjoyed translating poetry from Bengali to English, which was published as a book. I plan to do more of that.

What can we next expect from your pen?

I have been trying to finish a work of non-fiction about climate change and I hope to do this by the end of the year.

Let me also take this opportunity to thank you Mitali and your team at Borderless Journal for your service to literature. You are doing important work here and I am really grateful for your interest in my novel.

Thank you so much for giving us your time and sharing your wonderful book.

.

[1]Solarpunk is a sci-fi subgenre and social movement that emerged in 2008. It visualizes collectivist, ecological utopias where nature and technology grow in harmony. Read more by clicking her

[2]Navratnas or the nine gems were a bunch of very gifted men in his court, like Birbal and Tansen.

[3]The author does not agree to this reading in the interview. He sees his novel evolve out of the solarpunk movement.

[4]Alexandra David-Néel (1868-1969) https://openheartproject.com/the-path-post/alexandra-david-neel/

CLICK HERE TO READ AN EXCERPT FROM SPELLCASTERS

(The online interview has been conducted through emails and the review written by Mitali Chakravarty.)

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International