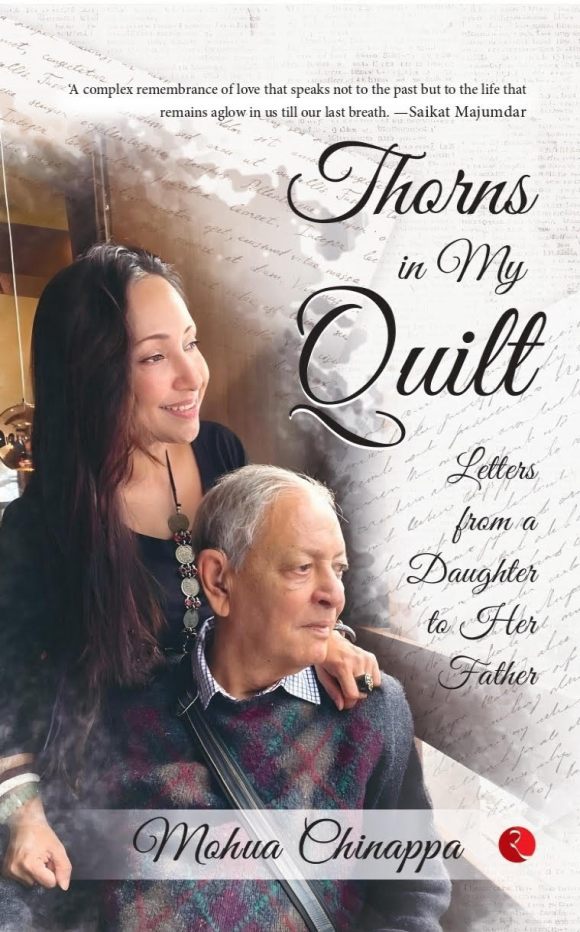

Title: Thorns in My Quilt: Letters from a Daughter to Her Father

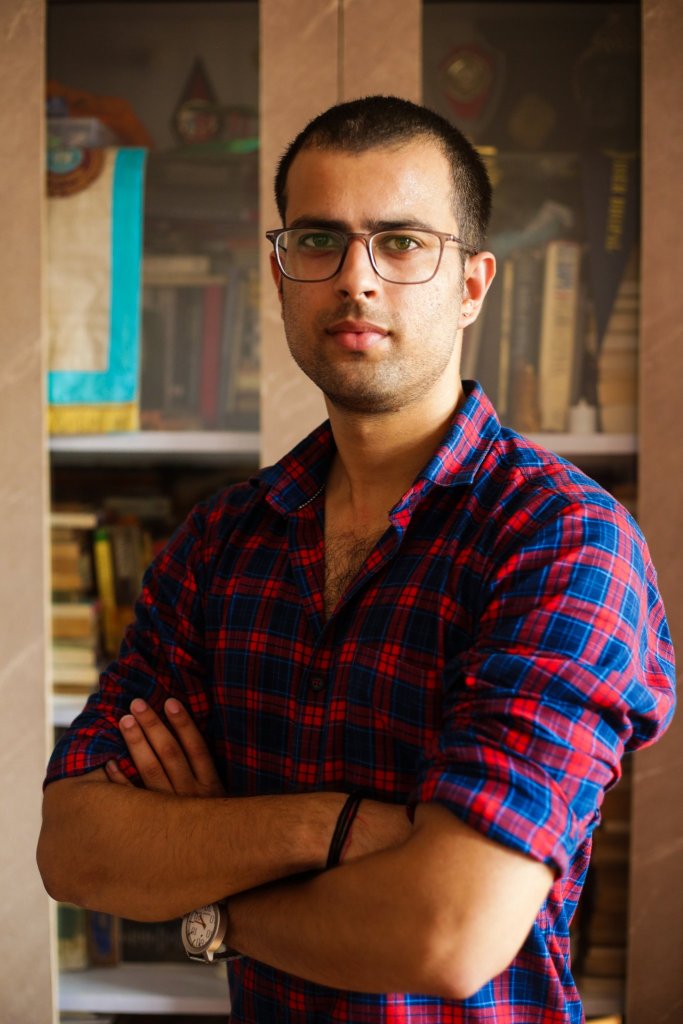

Author: Mohua Chinappa

Publisher: Rupa Publications India

LOSS

4 August 2022

Living Room, Bengaluru

Dear Baba, Today is your shraddho, the puja for your departed soul. Referring to you as a soul seems so distant. Calling you anything but ‘Baba’ seems like two strangers speaking to one another. The purohit is here to do the rituals. The atmosphere is sedate. The room is lit and the flowers in the vases are in full bloom. I am glad we have cousins in the city; otherwise, it would be very lonely for Ma and me. We know very few people who would make the effort to attend a staid function like a shraddho. How does one end a tie so deep with a mere ritual? One can’t. It does feel surreal to watch your photograph with a jasmine garland around the lifeless frame. The sandalwood phonta or tika on your forehead makes you look different. The living room has been cleared. The large antique box has been covered with a white cloth, and your photograph is placed on it in such a way that you are facing the direction that will lead you to the other world. The shraddho among Bengali Hindus is a ceremony that is performed to ensure a passage for the recently deceased to the other world. The rite is both social and religious and is meant to be conducted by the son. But you have no male heir. So I defy tradition and lead the puja. I follow the rites dutifully and chant the mantras, which don’t mean much to me. You are gone. There is no mantra that can soothe my heart. On the floor is a bed, laid out with a pillow and an umbrella for your onward journey to God-knows-where. I follow the purohit. Neel joins me in the ceremony. I feel so anchored, having him next to me. What a loving child he is. He makes life so much simpler for me. After the puja, we put out a plate of your favourite food so that a crow can come and eat it. Leaving the food in the corner of a lane seems ridiculous, but I have decided not to question any of the rituals, for I don’t want Ma to feel that I didn’t do my best. I leave the plate on the ground. There are bottles strewn around, and the ground is not very clean. I don’t turn back for another look. Your photo has now been removed and stands on my marble corner table. I put out the burning incense sticks and remove the flower garlands. It is still sinking in that I won’t be able to hear your voice ever again, calling out to me, asking me for something or the other. As we sit down to eat, Neel reminds me how you discussed Left politics and he argued with you on capitalism, just to rile you up in jest. You had such a wonderful bond with my child. I smile as I hear Neel mimic you and your quintessential Bengali ways of reacting to situations. Those debates between you both. I loved the way you both called each other Dadu. Baba would say, ‘Dadu, you must read about the world and its magnificent history. The great idea of how civilizations emerged, and how revolutions took place in protest against tyranny and oppression. As you read, you will learn that the world is a beautiful study of humanity and historical events.’ And Neel would say, ‘Na, Dadu, I will only read books that emphasize the profit and loss of capitalist businesses. Whoever cares about art and philosophy?’ Neel knew how you would go red in the face. And you would say, ‘No businessman ever built a nation; it is the thinkers and the dreamers who created a world of equal opportunities.’ This camaraderie you both shared remains the most beautifully preserved and poignantly pure memory of you with your grandson. I remember those days when you constantly waited to hear from Neel, and how the Sundays were marked aside to have your long-awaited conversations with him. You truly were a wonderful grandfather to my son. I feel empty as the furniture in the living room is rearranged to how it was before. Like nothing has happened, and no one is now gone forever. It looks as if you will come back in a minute, ask for a cup of tea and brood with your arms crossed over your chest. I think just being there to watch me do everyday things made you feel calmer. I don’t know. But I hope someday, I will understand the silence between us. Comfortable spells of silence, and some very terrifying ones. Like your death.

Love

Manu

*

5 August 2022

Bengaluru

Dear Baba, The vermilion has been removed now. The parting is stark white the hair oiled tied into a braid of acceptance. The grey mixed with the leftover black strands falling carelessly on her shoulder. I had seen her one lonely noon take a pair of scissors cut off her locks Like Samson and Delilah. She was at war A war with her own existence Her identity has been shaken Her oar is cracking open along with her broken sail. She sets to the seas but the land is far away on the horizon shining like the crystals found on a crown lost in a war lying forlorn for the head of the right king but now Samson is dead the Philistines have left too the palace has been torn down but parts are intact. Her locks sheared from guilt for being alive. Will she find her shore with her broken boat and tattered sail hoping the seas take her in or the fire of her breath is gutted before it becomes wild like a forest fire burning the little birds coloured kites stuck between branches and her capsizing boat too lost in the new world!

Love,

Manu

About the book:

Thorns in My Quilt: Letters from a Daughter to Her Father is a series of letters written by a daughter to her father after he passed away. Unspoken thoughts, unshared memories and unsaid words combine in this searing and poignant account of a relationship filled with joy, but with equal moments of sorrow.

Mohua Chinappa (Manu) loved her Baba, who was as kind as he was cruel, as well-read as he was unworldly, as loved as he was unloved. His dearest Manu recollects her childhood in Shillong, infused with the aroma of vanilla essence that went into the butter cookies he baked. She reminisces about her father holding her little hand while helping her through the undulating, rain-drenched roads. Mohua returns to Delhi, where she spent a part of her growing-up years, and revels in the memory of a government house with a harsingar tree. She writes to him about her broken marriage, recalls how her parents left her side, and how she reinvented herself. The letters are often selfish yet strangely cathartic.

Her father’s kidney failure prompted a daughter to confront the demons within—the loss, the doubts, the emptiness, the guilt of saying things, and the angst of not saying things.

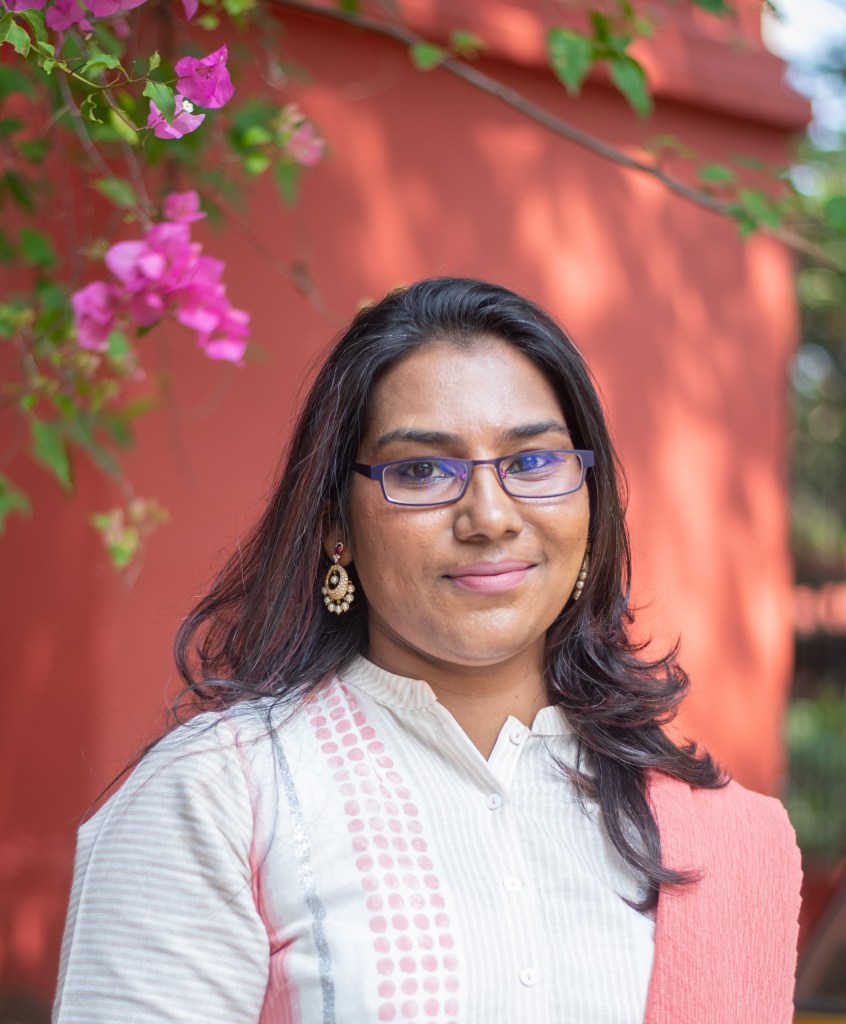

About the author:

Mohua Chinappa is an author, a columnist, a renowned podcaster in India, a TEDx speaker, a former journalist and a corporate communications specialist.

The Mohua Show, a podcast she started in 2020, has close to 2 million downloads. She contributes regularly to various national dailies and magazines, including The Telegraph, Deccan Herald and Outlook. She is regularly invited as a speaker on TEDx and Josh Talks.

Mohua’s other initiative—NARI: The Homemakers Community—provides a platform for homemakers to voice their everyday challenges.

Her book—Nautanki Saala and Other Stories—was awarded the PVLF Best Debut Non-Fiction (in English) Award 2023. She also has two poetry collections to her credit—If Only It Were Spring Every day and Dragonflies of My Dreams.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL