By Tan Kaiyi

“Are you sure it’s safe for us to be this close?” Anushka asked.

“I don’t know. They said it’s not over,” Rizwan said.

“Who says it’s not over?”

“It’s all over the radio,” Cheng said.

“All over?” Rachel asked.

“It was on every channel I was scanning this morning.”

“You can’t believe everything you hear.”

“It’s from the Ministers. The 6Gs.”

“We don’t even know who they are. All we hear about them is from the radio,” Anushka said.

“But everything they said had turned out to be true.”

“We aren’t sure of that. All we hear is the numbers of people who disappeared from some voice who claims to have the mandate to govern,” Rachel said.

“The voice had been right about the virus,” Rizwan said.

“If it’s a virus.”

“I don’t know what else to call it. It makes logical sense that the government would have a continuity plan, some kind of team after things fall apart.”

If the government was smarter, it wouldn’t have needed a continuity plan, Cheng thought. But then again, no one has seen anything like this. Who would be smart enough to know that people would start turning when two or three were gathered. Physical contact seems to be the main trigger, but reports had come in of people mutating even when they were near each other.

“Hey, watch the distance!” Anushka yelled.

“Sorry, let me move a bit,” Cheng said.

“I don’t want to become one of them, not at a time like this. Sorry, I don’t mean you have it.”

“I know, I know, I’m sorry.”

“It’s okay. Are you sure this is going to work though?”

“I don’t know,” Cheng said.

“We have to hold hands. I don’t think it’s a good idea,” Rizwan said.

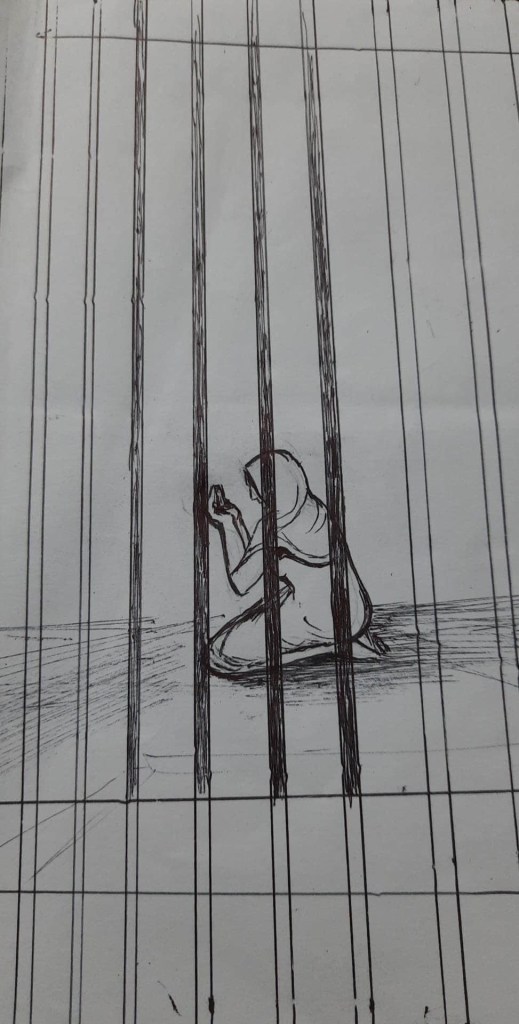

He looked at the symbols they have set up for the ritual. Five stars and a moon drawn in blood and white chalk on the ground. The four of them had seen it in their dreams, a city of glistening mirror colossi, glistening with the reflected sun under clean blue skies. It was so vivid that they could smell the aroma of the air and the soothing embrace of the heat. And the people! None of these horrid mutations that flailed and shrieked about. What they would have given to just walk down the street without the risk of getting mauled by their twisted limbs or infected by their touch! If they did the ritual right, that’s where they would be — or at least that’s what they thought.

“We don’t even know if it’s going to work,” Anushka said

“You’ve seen it. You’ve seen it in the dreams,” Rachel said.

“It could be that. Just dreams. Nothing more.”

“We’ve come this far, we’ve got to give it a shot.”

Rachel looked at her friend from secondary school. She wanted to tell her that it was alright, that once it was done, she was sure that the ritual would open up a better world for them. But she wasn’t sure. The legend had been circulating after the mutations spread throughout the world. The sickness was biological, but it was something more. There was talk that it could bend reality, which explained how the virus warped human physiology. When this idea spread through the airwaves, it led to several theories about a hidden gateway to a parallel world — similar to theirs but with a brighter fate.

“Lots of people have died to come to this place. We got lucky, we’re here now,” he said, remembering the many moments in their journey when they narrowly escaped death. Mid-way, Cheng had caught a bad case of fever and breathlessness, and he felt that his body was turning inside out. It was the most fearful experience he had in his entire life. Just put a bullet in my head, he told Anushka. He heard her refusals through her soft sobs, but he didn’t want to end his life as some kind of inflamed monstrosity. No one dared to go near him, and that sense of isolation fuelled his anguish. He didn’t know how they got through it but the fever faded after a week. It delayed the entire journey, and depleted their rations ahead of time.

Johnson, one of their original companions, died of hunger a few days after that. Since then, Cheng hadn’t been able to sleep well. Even if they succeeded in getting out of this place, he knew his feeling of partial responsibility over Johnson’s death would continue to demonise him for the rest of his life. The four of them readied the items. The candles were set around the six symbols painted.

“It looks a bit like our flag, isn’t it?” Rizwan asked.

“A little,” Cheng said.

“What do you think we saw?”

“I don’t know. But it sure looks better than here,” when those worlds rolled out of Cheng’s tongue, he realised how absurd it sounded. It didn’t bode well for hope. He was beginning to think that this was all a mistake. He tried to comfort himself by thinking that that the distance between them and freedom was that one metre which prevented transmission, but his heart began to tremble and he prayed that his fear wasn’t showing.

“That’s it. All we need to do is to hold hands and close our eyes,” Cheng said.

“How long?” Anushka asked.

“I don’t know. What did the stories say?” Cheng asked.

“They say you will hear crackling in the air and the stench of death will be gone,” Rizwan said. He was haunted by hesitations, but they had come this far. If ahead lay death, it was nothing better than what they were leaving behind.

“Are we ready?” Cheng asked.

“I don’t know,” Rachel answered.

“Let’s start with the first step.”

The first step could be the deadliest. They stared at each other for what seemed like lifetimes, before they slowly reached out with their hands. When their fingers touched, an icy sensation crept up their arms and spine. Cheng cursed. The foul words released the tension from his shoulders and throat like a magical incantation.

“We’re still normal,” Cheng said.

“That’s a good start,” Anushka said.

“Okay, then we just keep repeating the chant?” Rachel asked.

“Yes,” Rizwan said.

And they begin to sing. The words and melody filled their minds and the room. The lyrics and music were familiar, they sang it every morning before school started — though the tune of this version was slightly distorted.

Eyes closed, it was hard to tell how much time had passed.

They were lost in the words. As they became more absorbed into the verses, they felt themselves dissolve. But without opening their eyes, they couldn’t know what was going on. A thought came up in Rizwan’s mind. He felt removed from the entire process — like a disembodied eye that watched over them. They were still in the room, he felt.

There was nothing left to do but to carry on. And so they continued — drowning in the sea of words and time, waiting and waiting, only coming up to grasp the scent of fresh air.

.

Tan Kaiyi is on a literary odyssey to unearth the wonders and weirdness within the mundane. His poems have appeared in the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore (QLRS). His play, On Love, was selected for performance at Short & Sweet Festival Singapore. He has also been published in Best Asian Speculative Fiction (2018), an anthology of science fiction, fantasy and horror stories from the region.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.