By Lakshmi Kannan

The next two hours were free for Tara to spend them any way she desired. She wanted to maximise the time spent she spent with her dear friend Sunita who was admitted in a hospital near Mylapore, Chennai. She sat with her in her private room, took her lunch tray from the hospital staff, and personally served her as she reclined on the bed.

I must somehow restore Sunita to Sunita, she told herself. She was such a chirpy, positive person. How did this surgery take away all that from her?

In between sips of soups, mashed rice with dal and vegetables, Tara gently coaxed Sunita to eat well, to get strong so that her discharge papers could be processed, and she could return to the comfort of her home and slowly resume her work online. “It’s the digital era,” she said, as if it needed a reminder. “We now have the wonderful opportunity to work from home until one can resume work. So, Sunita, work towards that goal. We’re all waiting to see you on your feet again,” she encouraged. Sunita gave her a weak smile.

“What about your lunch Tara? It’s well past lunch time,” she asked.

“No worries. I’ve a car at my disposal, have made arrangements for my lunch. I’ll have a quick bite somewhere and join my family,” she assured. “Come on, have some custard. You must eat well, Sunita. Promise?”

Sunita nodded, her eyes incongruously bright on her wan face.

Tara tucked her back into bed, said goodbye with a thumbs up sign and came out of the room.

*

Waiting for the elevator, Tara recalled how she had warded off all the lunch-suggestions by her family before she came to the hospital. She told her family that she would grab a quick lunch somewhere and then join them for the rest of the day. Instantly, her family had pulled out their phones and googled for restaurants that would qualify as ‘good’ even if it meant driving some distance. Tara had responded that New Woodlands Hotel was close to the hospital, so she could use the time to be with her friend, then have a quick meal and join them. A chorus of voices said New Woodlands was just ‘okay’. “It has improved a bit, has a Family Section where you can get some privacy,” still it wasn’t one of the best they argued rather patronizingly. They suggested other outlets. One of them suggested that she drive past New Woodlands, get on to Anna Salai road and reach the Taj Connemara. “It has The Verandah restaurant with a multi-cuisine buffet. You can mix and match the dishes any which way you like and eat your fill.”

“Or try Raintree Hotel,” said another. “It’s also on Anna Salai Road.”

“Isn’t there a Rain Tree at Alwarpet? I heard it has a nice restaurant on the terrace, appropriately called Above Sea Level,” said another.

They showed her the Google maps and advised her to follow them on her phone. Poor New Woodlands, she thought, now relegated to a middle class eating joint, used only as a landmark by her family. “Go past New Woodlands…” — Ruthlessly bypassed after all these new fancy upscale restaurants have mushroomed in the city.

“Fine, thanks a lot. I’ll go to one of these you suggest and join you all soon, don’t worry, I’m on my own turf. So, I’ll sail through my way speaking in Tamil. The driver Dorai seems to be a nice chap. Bye for now,” she waved and was off to the parking space. Inside the car, Tara wondered why nobody in her family thought of where Dorai would have his lunch. Why ask him ‘to eat somewhere’ and then go to The Verandah, or Above Sea Level to pick her up? That will delay things unnecessarily. Why not have lunch at New Woodlands, both Dorai and I, she thought. That would be neat. It will cut the time taken for waiting. She had rushed to the hospital and was soon ushered into Sunita’s private room. She was glad she got some time to linger with her and coax her to eat lunch.

*

Tara came out of the hospital and got into her car.

“Dorai, please take me to New Woodlands,” she said. “We’ll both have lunch there, and then we’ll drive up to where my family is waiting for me,” she said.

He turned back and smiled. “Amma[1], I’ll drop you at New Woodlands and go to another place for my lunch.”

“Oh no! It’ll take time. That’s exactly why I suggested New Woodlands so that both of us can eat there and then move on.”

“No worries Amma. My votel[2] is also nearby only. It won’t take long.”

“I see. Why Dorai, don’t you like the food in New Woodlands? I’ve been there. It was so good.”

“Not just good Amma, it’s excellent,” he nodded.

“Then why do you want to go somewhere else?”

Dorai turned away and stared through the windscreen.

“What’s the matter, Dorai? Please tell me. Of course, you can eat wherever you prefer to.”

He turned back again, this time with a shy smile on his face.

“Amma, how can I explain? You won’t understand.”

“What!”

“Yes Amma, if I mention some dishes that only small, humble votels offer, you may not even know those items.”

“Such as?”

He grinned, but lowered his eyes. “Amma, there’s a small place called Annapurna Bhavan. It serves rare things like paruppu podi[3], mormilagai[4], vatral kuzhambu[5], karuvadaam[6], palapp pazham[7], a tumbler with neer mor [8]garnished with karuveppilai[9] and ginger and much more…”

Tara burst out laughing when she noticed that Dorai was almost salivating when he listed his favourite dishes.

“Wonderful, Dorai! I know those dishes very well, because I’ve grown up on them. I’m also very fond of them as remind me of my mother’s cooking when I was small. I’m glad you’ve located a place that has all these.”

“Amma, not only do they make these dishes well and put it all out on a large plate with cups. They also serve Amma, item by item, and they serve so ungrudgingly. It is as if satshat[10] Devi Annapurni[11] has descended, to give us food like a mother.” “Maybe that’s why it’s called Annapurna Bhavan!” said Tara, laughing.

“Hee, hee, yes!” chucked Dorai, nodding his head vigorously.

“Fine. Let’s both eat there.”

“Oh no! It’s not a place for you, Amma. I just can’t take you there. Saar[12] will be angry with me if he comes to know,” he protested.

“Then we don’t tell, Saar. Simple!” she smiled. “Dorai, I just told you how much I love the items you mentioned. It has been a very long time since I ate those things. I live in far-off Delhi, you see.”

“I know, I know, but Amma, it’s not a suitable place for you. Saar phoned me about The Verandah and the other place, Sea something…”

“Above Sea Level. No! I don’t want to go to all those places. Just take me to Annapurna Bhavan. I’ll tell Saar I went to The Verandah,” said Tara, firmly.

“Oh Amma, how can you tell a lie like that? Please listen to me. It has no parking area. I’ve to park the car on the main road and then walk through two narrow lanes to reach the votel. It’s a small one, you see.”

“I can very well walk on a lane. Come on, Dorai. Start the car or we’ll be late.

*

Tara got out of the car and Dorai led the way to another street that was cutting the main road at an angle. Vendors in carts selling vegetables and fruits were lined on both sides of the street. They walked for about two hundred meters when Dorai said, “This way, Amma,” pointing to the right. Tara followed him on a narrow lane that had a mix of houses, grocery shops and places for repairing cycle and scooter. A few stray cows ambled about lazily. Annapurna Bhavan was on the opposite side, joining two small buildings. Even as they entered the restaurant, the smell of food wafted over to the small reception in the front.

“Do you have a family section?” inquired Dorai.

“Ah…Yes. But I’m sorry. It’s full. If you wait for about half an hour, I can find a table in the Family Section for Madam.”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Tara. “I’ll go to the general section.”

“No, no! Can’t you try, please?” pleaded Dorai.

The man at the reception thought for a minute but shook his head to indicate that it was ‘full’.

“What I could do is to find Madam a table in the Ladies’ section, will that do?” he asked.

“Okay, okay, at least do that. Thank you,” said Dorai, still disgruntledby the whole idea, a ‘bad’ one, according to him.

He came with her till the door of the Ladies section and then pointed to the left.

“I’ll be going there Amma, to the general section,” he said.

“Have a good lunch, Dorai. No need to hurry. We’ve enough time,” smiled Tara, going into the hall that had multiple rows of tables. They were already occupied by women who were blithely chatting with one another. The hall echoed with their loud laughter and uninhibited chatter. Just as Dorai said, there were no large plates with multiple cups. Food was being served course by course on a banana leaf, like in a wedding. She was ushered to a table.

“One meal, Amma?” asked a waiter.

“Yes please.”

He placed a large banana leaf on the table, served her a steel tumbler of water and waited. She looked at him for a moment, then took the cue from others and sprinkled water on the leaf. She then cleaned it with her hand, like the women were doing. He placed another tumbler and poured thin butter milk into it from a steel jug. It was flavoured with curry leaves, ginger and salt.

“I will tell the boys to serve you a meal, Amma,” he said and left.

Tara sipped at the butter milk and looked around. Already, some of the women seemed to be halfway into their meal. The hall swarmed with women in brightly coloured sarees, their glass and gold bangles clinking on their wrists, their faces eager to catch up on news while they went on a sustained friendly banter over their lunch. It looked like many of them were friends who had fixed up a date and time to meet here, for a Girls Day Out, thought Tara. She was amazed to see the way they could keep a lively thread of conversation going while at the same time, they were mindful of what reached their ‘leaf’ and what got missed. Tara was amused to note that each one of them referred to her leaf impersonally as ‘this leaf’, instead of ‘my leaf’. Some women called out to the waiters variously as ‘Anne[13]’, ‘Empaa[14]’ and so on and said, ‘Here, give more poriyal[15] to this leaf. And that leaf needs rice, more rice! She called out for you, but you didn’t hear. Aiy Shenbagam, you asked for rice, di[16]!” said the woman looking after her friend’s ‘leaf’ along with her own. Tara noticed how they kept a tab on each other, like they were members of a family.

They had no qualms whatsoever, in demanding the men to serve them more. On the table next to her on left, and on the one opposite, sambar, and then rasam was being served. Another boy ladled out spoons of something. Instantly, the women mixed the rice and brought their hand to their nose to smell. Tara turned her face to the left and saw the same thing. Women brought their hands up instantly to their nose to smell.

Her meal came with varieties of vegetables, poriyal, karuvadam, fried appalam[17], and other things from the four-chambered cornucopia the man carried, so deftly. He put some paruppu podi[18] in a corner of her leaf and asked her to make a hole in the center. Then he poured some til[19] oil into it. Tara motioned him to come closer to hear her.

“Empaa, why are those women smelling the oil the minute it is poured into their rice?”

“Because it is not oil, Amma. It is pure is nei[20] that is poured for sambar and rasam rice. I’ll also be serving nei as soon as the boy gets hot rice for you.’ He smiled.

“Oh. All right. But why should they smell it, each one of them?”

The man laughed till his shoulders shook. “Amma, you seem to be new here. These women are all so clever and shrewd, you see. They want to check instantly if we’re serving them pure nei, or craftily passing off some oil as nei,” he grinned. “They’ll catch us by the neck if we cheat. Nobody can fool them. They’re all well trained in cooking, you see. They just come here for a change, to enjoy one day when they don’t have to serve their family or eat with their family watching. Okay, now let me ask the boy to hurry up with your rice,” he said, walking away with an amused smile.

Tara was fascinated. The women were clever to the core and didn’t want to take any chance. Ghee had better be genuine ghee, or else…!

Rice was served steaming hot. She mixed it with paruppu podi and til oil and relished the taste. It transported her to the days when her mother gave her and her siblings paruup podi whenever she couldn’t find the time to make sambar and was busy with other things. PP had gone out of the menu, and the lexiconof Tamil cuisine. The potato poriyal, the simple dish of fresh sautéed string beans with soft coconut scrapings, and the koottu[21] made with white pumpkin – everything was tasty. More rice was served, with hot sambar[22] into which the man poured ghee. Tara could smell it without bringing the mix to her nose. The man gave her a broad smile. Tara noticed that it was the same man who had served her til oil with paruppu podi and explained why women instantly took their hands to their nose the minute ghee was served.

“Don’t want to smell the nei, Amma?” he smiled, with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. Tara smiled back at him, nodded and smelt her hand just the way the women were doing. The aroma of pure ghee filled her heart. The man laughed and said, “I’ll now bring rasam[23], Amma. Want some more rice?” he asked.

“No, I’ve enough rice. Just bring me rasam.”

“Very well Amma. You’ve hardly eaten anything,” he said, before he went.

“This leaf didn’t get payasam[24],” said a woman loudly, on the next table.

“This leaf needs some koottu.”

“This leaf…”

“This leaf…”

“Anne, this leaf…have you forgotten?”

“No, no! How can that be? I’ll get it for you, in a minute.”

Tara watched, fascinated by the informal camaraderie between the women and the men who served them. The woman sitting at the opposite table told her waiter, ‘Anne, why are you ignoring this leaf? You’ve forgotten to even ask me if I need more rice, or poriyal.”

“Ayyo, excuse me thangacchi[25], I didn’t do it on purpose. Someone else was calling me and …here you are,” he said, ladlingout rice with a large, curved serving spoon. “What would you like with it, morkuzhambu [26]or sambar again?”

“Both!” said the woman, bursting into peals of laughter that was echoed by her companions at the table. One woman teased her for stuffing herself with enormous quantity of sambar rice. “Watch out Shenbagam, or you’ll put on weight,” she warned.

“Shut up, di! I feel like I’ve come to my mother’s house. I can eat as much as I want without…”

“Without your husband’s elder sister, or his widowed aunt, or your mother-in-law staring at you with a frown?” she helpfully completed the sentence for her. “Exactly! They think we women should not eat heartily, it’s considered unseemly,” she said, slurping her rasam.

“Well then, let them come and take a look at us. We’ll show them how decorous we’re in eating,” the woman laughed. Other women from the tables joined her and there were squeals of laughter all around that group.

“Amuda, Aei Amudavalli[27]!” said a woman.

“Did you have morkuzhmbu? It’s A-1. Have some more, it’s your favourite.”

“I will Akka, thanks for reminding me,” said Amuda.

Another man came with a small steel bucket of koottu. “Anybody wants koottu? Come on all of you, eat well, eat shamelessly,” he repeated. Two women smiled and started teasing him.

“Anne do you help your wife in cooking, at your home?”

“What! what a question?” he chuckled, pausing for a minute with the utensils in his hand. “Home is a different matter, why’re you talking about home? Forget everything now and eat heartily.”

“Tell us, Anne. Isn’t your wife a very lucky woman that she gets to be served by you?”

“Oh ho! You naughty women. Yes of course, she is lucky, but home is a different place,” he grinned.

Another woman said, “Anne is very clever. He is dodging us. I bet he doesn’t serve his wife at home. It is she who has to do that. Am I not right, Anne?”

“Stop gossiping and hurry. People are waiting outside for their turn. Shall I get you jackfruit and honey?” he said, turning to walk out of that row.

Again, there was a peal of laughter. One woman screamed above the din, “You’re a very good man, Anne. Really.”

Tara forgot the food on her leaf and watched fascinated. The warm banter between the women who gobbled upthe food from their leaf and looked after the ‘leaf’ of their friends, and the men who served them generous helpings of whatever they wanted in a reversal of role — both of them seemed to have moved on to another stratosphere! The women looked so happy, and so did the men who put a smile on their face.

Tara returned to herself when she heard the man say, “Amma, let me get some fresh hot rice for you, and then curds.”

“All right.”

He came back with rice and curds that he served with mormilagai. He kept a small plastic cup and poured payasam into it. From another large steel bowl, he took out freshly peeled ripe jackfruit. Tara looked at the gold-hued fruit. Each one of them had an opening on the top. The man waited.

She looked at him, not knowing what she was supposed to do.

“Amma, won’t you hold out your jack fruit for some honey? I’ll pour some for you,” he said.

“Oh, yes. Sorry I made you wait. Here, please pour the honey. This is fantastic!” said Tara. She had forgotten for a moment that Dorai mentioned jackfruit as part of the menu.

The man poured honey carefully into each one of the fruits on her leaf.

“Anything else Amma?”

“Eh… no. Let me eat this first. I feel so full.”

“There’s no hurry. Please take your time. Call one of us when you need something. We’re all here,” he said and bustled over the next table.

“Who wants more payasam, or jackfruit?” he asked, glancing at the row of women on the two tables.

Tara ate her jackfruit nervously, worried if some honey would dribble over her dress. There were no tissues around this place, but who cared? She pulled out another handkerchief from her handbag and sucked in the honey carefully. What a great combination — jackfruit and honey. She remembered Molly, her friend from Kerala who would often bring a delicious sweet prepared with jack fruit. After the routine school lunch with their mutual friends, the two of them would escape for ten minutes to the playground at the rear portion of the school, find a shady place to sit and share the sweet in secret.

Tara’s long hair was parted in the middle, plaited in two sections, then folded double and secured with satin ribbons on both sides of her head. She was eating at home with her siblings and cousins. Some honey had already dropped on to her school dress. Must wash it of before she left for school. Also, she would have to brush her teeth to subdue the fragrance of jack fruit or else, she wouldn’t be able to open her mouth to speak. People would instantly find out that she had eaten jackfruit. She’d tell her mother that from tomorrow, she would have jackfruit after she returned from school.

No time to compete with her cousins that day. “Four.” “My score is seven.” “Eight,” boasted another.

“You’ll get sick,” she warned, as the boy carried on nonchalantly, swallowing one fruit after another.

Through the window of the dining room, Tara could see the rear garden of their house. The banana tree laden with purple banana fruit, the tall, gnarled jackfruit tree that seemed to ‘stand guard’ over the garden like an old, trusted care-taker. The fragrance of jasmine floating from the plants, the heady smell from the marukkozhundu patch from the right side of the window…

“Hurry Tara, or you’ll be late for school,” her mother was urging her to eat fast…

“Amma, shall I get you some more payasam? Did you like it?” asked the friendly waiter.

“Thank you. It’s very good and I’ve already had a lot. I’m full.”

“Then let me get you another tumbler of neer mor. It’s a digestive. The ginger in it will make you feel better. And when you go out, please have beeda[28] from the reception. Each one is wrapped with thalir vetrilai[29]. It has kraambu [30]and that’ll also help in digestion,’ he suggested.

He offered a plate of saunf[31] with small pieces of kalkandu[32].

She put some in her mouth and placed three hundred- rupee notes on his plate.

“Amma! It’s too much,” he protested.

“Sshh! Just take it. You transported me to my childhood today, even if was for only one hour,” she smiled. “And all of you have given a happy Girls’ Day Out for these women who slave in the kitchen every day,” she thought, glancing over his shoulder to take one last look at the chattering women. Their voices rose above the din and clatter of waiters who walked up and down the aisles between the tables. The man took the money with a smile and pressed his palms together. He accompanied her to the door. Dorai was waiting for her, his face a picture of consternation.

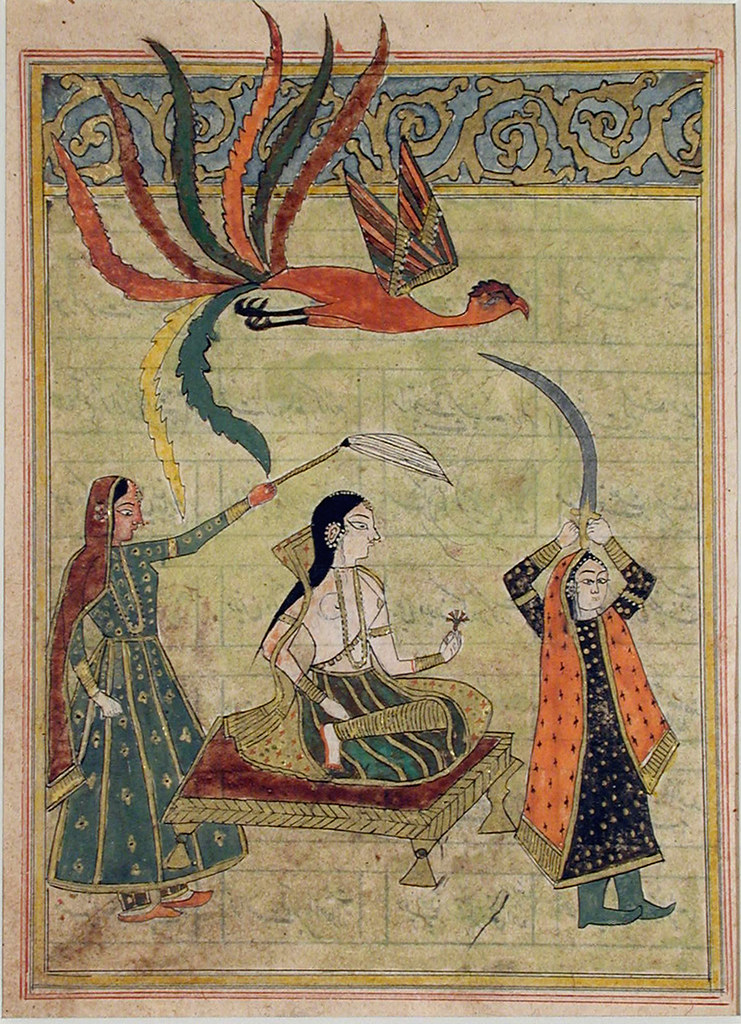

Tara beamed a smile at him and at the man who was now pointing at the beeda on the reception table. She paid for two, gave one to Dorai and walked out. It felt as is a great weight had slid off from her shoulders. She felt light on her feet. To think that she had re-lived her childhood in the most unlikely of places, and in a totally unexpected way… A bird fluttered its wings and flew out of her chest. As she walked out of the place, the chatter of women in brightly coloured sarees floated behind her, their care-free laughter, their bangles tinkling on their arms, faces lit up with mirth and mischievous jokes while they bonded over food and the serving waiters. Their mother Annapurni watched, waving a wand of bonhomie that wrapped around each one of them.

[1] Mother. Here used like ‘madam’

[2] A typical way of pronouncing hotel by people in Chennai.

[3] Roasted lentil that is powdered with pepper and other ingredients. It is mixed with rice and oil and is a favourite side dish.

[4] Chillies that are soaked in buttermilk, and then dried in the sun. They are used after frying in oil.

[5] A preparation made with dried vegetables and thick tamarind solution.

[6] A salty, spicy preparation made with a combination of rice, bengal gram and other ingredients ground into a moist paste, and then dried in the sun. It is fried in oil and eaten with meals.

[7] jack fruit

[8] Thin buttermilk.

[9] Curry leaves.

[10] Like someone has actually appeared.

[11] Also called Annapurna or Annapurneshwari, she is known as the Hindu goddess of food and nourishment and is believed to be a manifestation of Parvati.

[12] Colloquialism for Sir

[13] Brother

[14] An informal way of addressing a male

[15] Fried vegetables

[16] Elder sister

[17] Made with black gram and sundried before being fried. Called papad in Hindi.

[18] Roasted lentil that is powdered with pepper and other ingredients. It is mixed with rice

[19] Sesame

[20] Clarified butter or ghee

[21] Vegetables cooked with lentils and coconut.

[22] Spicy lentil cooked with tamarind juice in Southern India.

[23] Thin lentil soup made with tomatoes and cumin seeds.

[24] A dessert made of milk and rice

[25] Younger sister

[26] Also called southern wood, it’s a leafy plant with a strong fragrance

[27] Aei is an intimate way of addressing a close friend, like ‘hey!’ Morkuzhambu: A spicy dish made with sour curds

[28] Roll of betel leaves with pieces of areca nut, clove, coconut scrapings and other aromatic ingredients.

[29] Tender betel leaves

[30] Clove

[31] Fennel

[32] Rock-candy

Lakshmi Kannan, also known by her Tamil pen-name ‘Kaaveri’, is a bilingual writer. Her twenty-five books include poems, novels, short stories and translations. For details regarding the fellowships and residencies she received, please visit her website http://www.lakshmikannan.in

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles