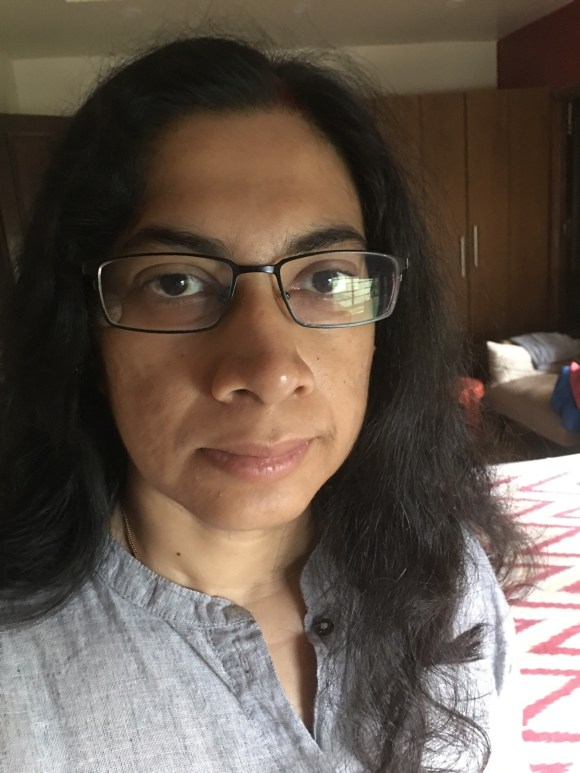

Relive the terror of the 2008 Taj Mumbai attacks in this gripping nostalgic retelling by Bhavana Kunkalikar

I wish I could turn back the clock and bring the wheels of time to a stop. Turn it back to the days before the nightmare began; a nightmare that lasted three dreary days.

It was my parents’ 25th wedding anniversary. To mark the occasion, I booked for them a special dinner and an overnight stay at the Taj Hotel.

Over the last few days, food and water and sleep ceased to be the needs for survival as I sat glued to every fragment of the television news which named all the victims of the hostilities. My parents were famous local authors and often in the news, but this was probably the only time I did not want to hear their names on television.

Also, over the three days came numerous phone calls from all my relatives, asking whether we all were safe from all the inhumanity. Unable to face my parents’ absence, I reassured them.

“How sad is all this! These terrorists will be cursed to hell, I tell you. What have we Mumbaikars done to these Pakistanis? A three-day siege! How sad is that! I haven’t even eaten anything since this has started, you know.” said an aunt as a pressure-cooker whistled in the background and I hung up.

Today was the third day of the siege. The early morning news promised the capture of the attackers. A ray of hope finally. I obviously knew that this would have an end but the feeling that it was all happening and finally I would meet my parents was heartening.

As our troubles now seemed bleak, I made a much-needed cup of coffee for myself.

According to my mummy, coffee was a wonder-drink. It worked again.

I moved back to the armchair with my coffee and covered myself with mummy’s blanket. This armchair was dad’s “favorite place to be” and was hence out of bounds for anybody else. Thus, in his absence, I and mummy would take turns to sit on it. Not because the armchair was anything special but probably because forbidden fruits are tastier.

And even today in his absence I had spent a good three days on this chair. Only half-hoping to see dad storm through the door and ask me to “leave the chair alone!”

And the blanket smelled heavily of mummy — as if it still had a piece of her in it.

Soon but not enough, the TV headlines blared “It’s over!” signifying the capture of the last of the attackers.

Well, it wasn’t over, was it? Uncountable lives and families were disrupted in a matter of three days by a bunch of men who claim to do this in the name of their religion. A war they started to “protect their God”. It really wasn’t over.

But now wasn’t the time to deal with that. Now was the time to leave the warmth of this house and face the heat of those enemies. It was time to confront the destruction suffered by the city I grew up in. It was time to finally discover the voices behind all the screams I heard those nights. But all this was what I was frightened of.

And yes, it was also time to get my parents back home.

I changed from my pajama suit to the ever-duty jeans and t-shirt and shut the television in what must be the first time in three days. Gulping down the cold coffee in one sip, I rushed to the door.

The slight sway of the armchair just before I locked the door shut, made me feel the armchair was worth nothing without them. The house could never be my home without them. I was nothing without them. We all needed them.

And I did not need to spend another night enduring those screams without them.

As I hit the road with my scooter, a gloomy winter sky welcomed me. At 8.30am, the sun did not shine as brightly. It somehow seemed as if it did not have the need to shine anymore. As if the happenings of the previous nights had left it all hopeless. It seemed to rise only because it had to, not because it wanted to. Even the sun had run out of options.

This train of thoughts ended abruptly as I brought the scooter to a sudden halt. I had nearly missed hitting a dog as it scampered away screeching.

My gasp of surprise stayed stuck in my throat. Hurting another innocent being even unintentionally was a shuddering thought.

And there they were. Having a “well-deeded” massacre.

After twenty minutes of what seemed to be an obstacle-less ride, I reached the hotel. And the sight there was spine-chilling.

One of the floors of the building stood ablaze. Ablaze not in fire, but in smoke. The pictures of the burning building doing their rounds on the television news left little to the imagination.

One couldn’t help but wonder. What must it have been like to be there? Enjoying a lovely meal and to be suddenly attacked and shot at by complete strangers? What must it have been to realise that this would be the last minutes of one’s life? A topsy-turvy life to be ended by a reckless bullet?

What would it have been like to shoot all of them down? Did the attackers not think of how those ‘hostages’ had a family to go back to? Could they not imagine how it would feel if a bunch of strangers were to kill one’s family?

Tearing away my gaze from the day-old smoke, I saw a group of khaki-clad men trying their best to protect the building’s entrance. Policemen.

Another group of people, a definitely larger one, were trying to force their way in. A wave of immense grief seemed to run through this crowd. Crying and howling with sudden angry outbursts, they appeared to push against the policemen with all their strength but not quite. The victims’ families.

More hopefully, the survivors’ families.

The atmosphere was tense with these opposing forces. Even with all the noises around, the air weighed heavily of deafening silence.

It took me a moment or two to realise that I stood surrounded by striking contrasts.

As I stared wide-eyed at the scene around me, I noticed a young lady in the crowd. Must have been about the same age as me. She had just stopped in her attempts to be heard, to catch her breath and wipe her rolling tears away. As she did so she caught my eye. Something about my face made her give me a sympathetic smile before she continued with her protests. Instinctively, my hands searched my face.

I was crying.

With my spent tears I made for one of the benches. With my back to the Gateway of India, I knew that this bench, like most people, had experienced happier memories; much unlike this new one.

Quite a few years ago, when I was ten years old and when we were financially not so comfortable and when even a breakfast in Taj would be an unaffordable luxury and when mummy’s coffee obsession had just started, my parents and I had come to visit this place. It was their twelfth wedding anniversary then.

I loved balloons. And I still do. And a visit here bought me loads of them. When I say ‘loads’ I mean one each for me, mummy and dad. I had then thought that they would get those balloons for themselves because they liked playing as much as I did. The fact that I was the only one who’d play with all those three balloons was a different matter.

That particular winter evening, the winds were at their strongest. A few gusts later, the balloon in my hand flew away and drifted away into the wind. I ran after it as my parents ran after me. But the balloon turned a deaf ear to all my yells and was soon out of sight.

As I gave up the chase and stood in sadness, a hand with another balloon came in front of me. I looked up to see it was dad with his balloon.

“Take this,” he said.

“But it’s yours,” I replied.

“We’ll share it then!” he said immediately as his twinkling eyes closely resembled his sapphire finger ring.

Being under the impression that dad too must love his balloon a lot, this offer seemed like a big sacrifice to me. I mean, there was no way I would share my balloon with anybody. This made dad’s action a generous one for me then.

That’s probably what they meant when they said, ‘sharing is caring’.

The sapphire ring? Dad says he inherited it from his father who got it from his father. As I was the only child, the sapphire would next be mine.

“You’ll have it when the time is right,” is what Dad would say whenever I’d ask him about the ring.

Dad had his own unique way of seeing things. To him, everything and everyone had some mysterious air around them. To me and most people who knew him, Dad himself was worth a secret or two.

The sapphire ring was amongst the many objects of fascination for me.

“This ring, you see? It dates back to my great-grandfather. Some say he was gifted the ring by a king of his times. Others say he won it in some gambling game. But no one knows for sure. But what we do know is that sapphires of this shade are quite rare. Worth a fortune maybe. They say that darker the stone, the heavier it is. And impure too. The brighter it is, the lighter and purer it gets; that goes without saying. It’s pretty much like our conscience, you know.” Dad would often say.

Holding back my response, “No Dad, I don’t really see”, I would simply nod and further admire the ring.

It was beautiful. And it was indeed a spectacular blue. A blue so bright that it would put the best of skies to shame. And the cuts at the stone’s edges only helped the brightness furthermore. One could see directly through the stone which was considered a proof of its purity. But it also would reflect some amount of light. It truly was beautiful. But in no way did it represent the “conscience” to me, no way.

As a tiny smile lit up on my face, a harsh cry snapped me back to reality.

After another thirty minutes of unyielding wails, the crowd dispersed and settled down on the benches around me. As minutes passed, the cries reduced to occasional sniffles.

On the nearby benches sat a man in a prayer topi while another elderly woman was fiddling nervously with her rosary beads.

But that makes no sense, does it? Those terrorists and their organizations have always claimed that their “works” were to protect their God, their Allah. Attacking people of his own “clan”, like that topi-wearing fellow’s family, is what makes no sense at all.

In fact, I think this whole discrimination thing is all nonsense. Discrimination amongst religions and castes, I mean. But no — I’m not against religions, not at all. My religion makes me who I am; our religions, faiths make us who we are. The problem, I daresay, is that we tend to think that our religion is better than any other.

Because it’s not.

Everyone’s religion is just as good, or as bad as any other. That’s probably what they meant when they spoke of ‘equality’ then.

Yet another howl brought me out of my trance. Except this howl was a happy one.

The policemen had finally given us way inside the Hotel.

We all ran towards the entrance but were suddenly halted by the scene inside. The usual cheerfully well-lit area was replaced by a dull, bloodshot scenario. The air in here was even heavier.

One step at a time, the crowd dispersed, following its own direction.

Detaching from the crowd, I wandered pointlessly amongst all the expensive debris. It was then that I noticed it.

A few feet away from me on the floor something sparkled brightly, reflecting most of the light that came through a broken window.

Half-knowing what it was but half hoping it wasn’t, I walked towards it. And I picked up the sapphire ring.

Just then a scream echoed in my ears; the scream that’s been haunting me the following three nights. Only then did I realise. It was my mother’s scream.

I looked around to see the members of the crowd wandering as pointlessly as I did. Neither of them even showed any signs of having heard anything.

The heart denies what the brain already knows.

Pocketing the ring, I wordlessly left the building and came back to my scooter.

After one thoughtless moment, I wore the ring on my left index finger. This was NOT the right time I was waiting for.

Like the conscience, he’d said. Our conscience shouldn’t be impure, to say the very least. If the conscience has its taints it gets heavier, which makes living quite uncomfortable. Agreed. One’s conscience should be transparent, yes. Nothing to show, nothing to hide. Very true. But reflective? By taking inside all the goodness and also giving back the goodness received. Maybe that’s what he meant. Maybe I do see.

As the noon sun now poised itself, the warm winds ruffled my hair and tears on my ride back home. All I could do now was to keep hoping; hope that I’ll live with a gaping void, hope that justice will be finally served, hope that I would never let the sapphire darken.

Because that’s what mummy and dad would want their Afreen to do.

Bhavana Kunkalikar, a pharmacy graduate, juggles between writing and her career.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.