A Review of Nitoo Das’s Crowbite by Basudhara Roy

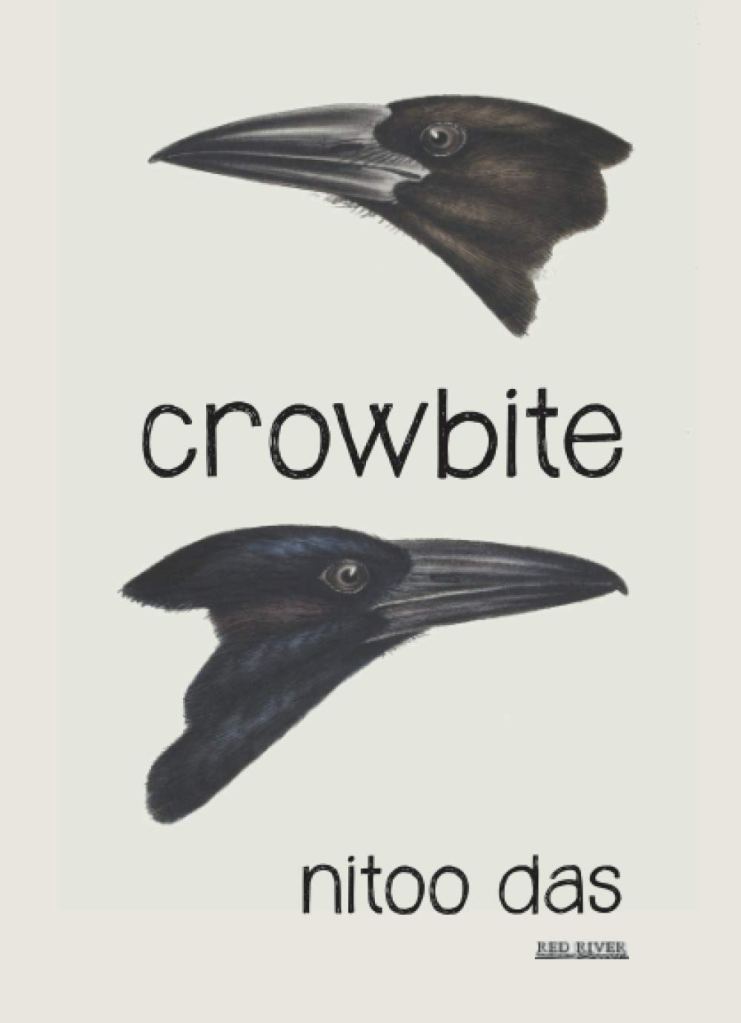

Title: Crowbite

Author: Nitoo Das

Publisher: Red River, 2020

In her essay, ‘Woman and Bird’ in What is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics, poet and essayist Adrienne Rich describes her sudden sighting of a magnificent great blue heron, a bird she has never seen from close quarters before and this brief encounter leads her on to a dialogic exploration of “all the times when people have summoned language into the activity of plotting connections between, and marking distinctions among, the elements presented to our senses”, of the potentiality of making such experiences the means of interpretation of poetry and life. Concluding the essay, Rich writes:

“Neither of us—woman or bird—is a symbol, despite efforts to make us that. […] I made no claim upon the heron as my personal instructor. But our trajectories crossed at a time when I was ready to begin something new, the nature of which I did not clearly see. And poetry, too, begins in this way: the crossing of trajectories of two (or more) elements that might not otherwise have known simultaneity. When this happens, a piece of the universe is revealed as if for the first time.”

One of the apparent reasons that this essay comes to my mind after reading Nitoo Das’s third collection of poetry, Crowbite, is of course the fact that both these writings are undeniably watermarked by the experience of birdwatching. Nitoo Das, professor, bird watcher, bird photographer, and poet with many anthologies under her belt, profoundly echoes Rich’s idea of poetry here – “the crossing of trajectories of two (or more) elements that might not otherwise have known simultaneity” and its revelation of a piece of the universe that has been scarcely perceived in the same way before.

As powerful as they are beautiful, as experimental as they are traditional, and as astounding as they are soothing, the thirty poems in this collection will take the reader on a journey that begins concretely in place and culminates in an existential place-less-ness that haunts both without and within. Close attention to topography is an important feature of Das’s poetry and each poem in Crowbite is testimony to the poet’s intimate communication and engagement with the landscape of her hometown in the hills. While even a cursory glance at the titles in the book reveals an intense grounding of most of these poems in a physical locale – like Mawphlang, Laitkynsew, Tawang, NEHU, Ka Kshaid Lai Pateng Khohsiew — all poems here are undoubtedly contextualized in a well-defined geographical space. Arne Naess in Life’s Philosophy writes, “There is a telling German word, Merkwelt, for which the closest English equivalent is “everything that a definite being is aware of”. When it comes to landscape poetry, Das’s Merkwelt is profoundly rich and she can penetrate the ostensible and concrete in it to arrive at the unusual and remote. In the poem ‘Root Bridge, Mawlynnong’, for instance, roots find their being in a metaphor from the world of fiction:

These roots are words that many hands have looped into a tale

With dangling subplots, conflicts, an infinite resolution …

In ‘Spotting a Spotted Forktail’, the “yin-yang bird” acquires an unusually graphic description:

He sprints

like the scattered prints of a newspaper.

he is a chess game speckled

with dots. A zebra bird

with strategic fullstops.

A monochrome

forktrailing a contrast

where the Rhododendron drops.

There are many markers – geographical, cultural and linguistic – with the North-East manifesting a presence as a protagonist within this collection. The poems themselves take on the serenity and wonder of the landscape they describe. However, it won’t take the reader long to realise that Das’s poetry, though, it stems from a territorial response to being and belonging in physical space, enacts itself essentially in the mind. Her landscape, rich though it is, telescopes almost inevitably into her mindscape and it is from this that her images acquire their rich visceral quality.

Examine, for instance, the opening and closing poems of the collection. The opening poem, ‘Mawphlang’ begins with a physical forest that threatens constantly to slide inwards:

The forest is something indecisive

between twig and soil.

It is an old woman opening

her mouth. She has nothing to reveal.

The closing piece, ‘The Cat’s Daughters’, as surreptitious, as mysterious and as metaphysical as the cat itself, closes with a journey that is decidedly inwards, a call towards primordiality, a return to the womb:

We imagine

our mother aging. We worry about her. She tells us:

If the basil dies and the milk curdles, come

save me. And so,

the basil dies and the milk curdles

and we go off on our travels. No,

we marry neither the merchant

nor the river prince. We birth

neither pestles

nor pumpkins. We want to find

our mother, see her silver eyes, touch

her old fur,

kiss her fish-mouth again.

It is this essential spatial tension between the landscape and the mindscape that accounts for a very different sense of temporality in Das’s poems, a fact that strikes one quite early into Crowbite. Though these poems are nourished by a deep affinity towards the natural world, the temporal rhythm they owe their allegiance to is neither chronological nor geological but purely intellectual, something I would call, mind time. Whether, it is observing a forktail, a leaf, a waterfall, an elephant, the rhododendrons, a painting or even a bus, Das’s reflections follow their own trajectory, their unique ratiocinative beat and it is through the subconscious meeting of these trajectories that her powerful poetry is born.

Poems like ‘Leaf in My Room’ and ‘In Which Mawlynnong is a Fractal’ are brilliant poetic ratiocinations explored through questions and answers. While in the former, each answer leads to more questions and in the latter, the questions don’t stop for answers, in both the poems we are brought only and amply close to the understanding of language’s failure to ask or answer, and in turn, to know or mirror the world. And this overpowering awareness of the powerlessness of language to make sense of the world is perhaps what bestows its greatest strength to Nitoo Das’s poetry.

Devdutt Pattnaik, a mythologist, in his article ‘The Song of the Crow’ writes:

“The word ‘why’ is translated as ka in Sanskrit, the sacred language of Hinduism. Ka is the first consonant of the Sanskrit language. It is both an interrogation as well as an exclamation. It is also one of the earliest names given to God in Hinduism. During funeral ceremonies, Hindus are encouraged to feed crows. The crow caws, ‘Ka?! Ka?!’ It is the voice of the ancestors who hope that the children they have left behind on earth spend adequate time on the most fundamental question of existence, ‘Why?! Why?!’ In mythology there is a crow called Kakabhusandi who sits on the branch of Kalpataru, the wish-fulfilling tree. The tree fulfills every wish but is unable to answer Kakabhusandi’s timeless and universal question, ‘Ka?! Ka?!’ “

Though the eponymous and incredibly moving poem ‘Crowbite’ in the book is engendered within a different cultural mythology and worldview, the crow remains here, as elsewhere, a “cawcawcaw of black” a cry connecting the soul to the Earth, a question-mark on civilization, a suspicion, a misgiving, a patch of darkness on the possibility of knowledge, an epistemological interrogation, a stark reminder of human vulnerability. In the closing lines of the poem, the crowbite that pursues Bhobai like both prophecy and legacy, becomes a metaphor not just for creative freedom but also existential freedom. It is freedom from civilization and its hierarchies of truth and knowledge, a crossing over of boundaries – from physical to metaphysical, and an affirmation of the ultimate embodiment of the world. Bhobai the man becoming Bhobai the crow acquires an in/sight that is terribly human and yet beyond the scope of the average, fallible person:

I went wherever I wanted to. I looked at people’s eyes and knew their secrets. I sang songs with the fishermen. I bathed in the sacred river and flew away from their temples before they could throw stones at me.

A word must be spoken for the publisher, Red River, whose superb designing of the book immensely succeeds in drawing attention to the tactile and visceral quality that inhabits these poems. Not to be missed are the remarkable illustrations by the poet that by bringing in another dimension of visuality and experience, lend a sinewy force to the overall interpretation of Crowbite – a collection that will as swiftly make a home in the readers’ hearts as it makes its way to their shelves.

.

Basudhara Roy is Assistant Professor of English at Karim City College, Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India. Sheis the author of two books, Migrations of Hope (Criticism; New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers, 2019) and Moon in My Teacup (Poetry; Kolkata: Writer’s Workshop, 2019). Her second poetry collection, Stitching a Home, is forthcoming in 2021.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.