Narrative and photographe by Prithvijeet Sinha

Lucknow bears the identity of an old soul always beholding glory and cultural heydays that have not altogether faded. The afterglow of its architecture, spiritual antecedents rarely misses the mark. After being pulverized by the lost revolution of the First War of Independence (1857), it transmuted its fearless legend to the present day, it’s hard not to think about the city’s twin children who breathe new life to it.

Shah Najaf Imambara and Sibtainabad Imambara are nestled just ten minutes away from each other within the historic and unmistakable centre of Lucknow- Hazratganj. But they cannot be summarised in pithy words. For if serenity draws us closer to our own tranquil and fuller selves, they play a huge part in orienting us towards a spiritual life that’s almost impressionistic.

Built under the aegis of Nawab Ghazi-ud-Din Haider in 1818, Shah Najaf Imambara derives its name from Shah-e-Najaf (King of Najaf), leaning towards its Shia origins and a place of spiritual importance in erstwhile Iran. Once again, these imambaras/ mausoleums were made in such formative fashion that the distinction between a royal estate and a resting place for architects of the region almost blurred. Today, it’s taken as the burial place of Nawab Ghazi-ud-Din Haider and some other pivotal family members. But on every occasion where the spirit meets holy chants and inner emotions especially during Muharram, Shah Najaf Imambara celebrates human valour to let the timeless strains stir those that need history to guide the present.

Two doorways usher us towards the main structure. The first has two lions almost standing as eternal sentinels while the second one has arched designs, windows in striking sky blue and turrets to welcome us. Then, past a garden and symbols of umbrellas and pillars on both sides, we enter the domed structure with a golden spire. The initial architectural framework has a miniature castle-like arrangement and pillars. Then the unique indoors open to wide verandahs, huge walls resembling those of a palace while stained glass windows and floral patterns catch our eyes.

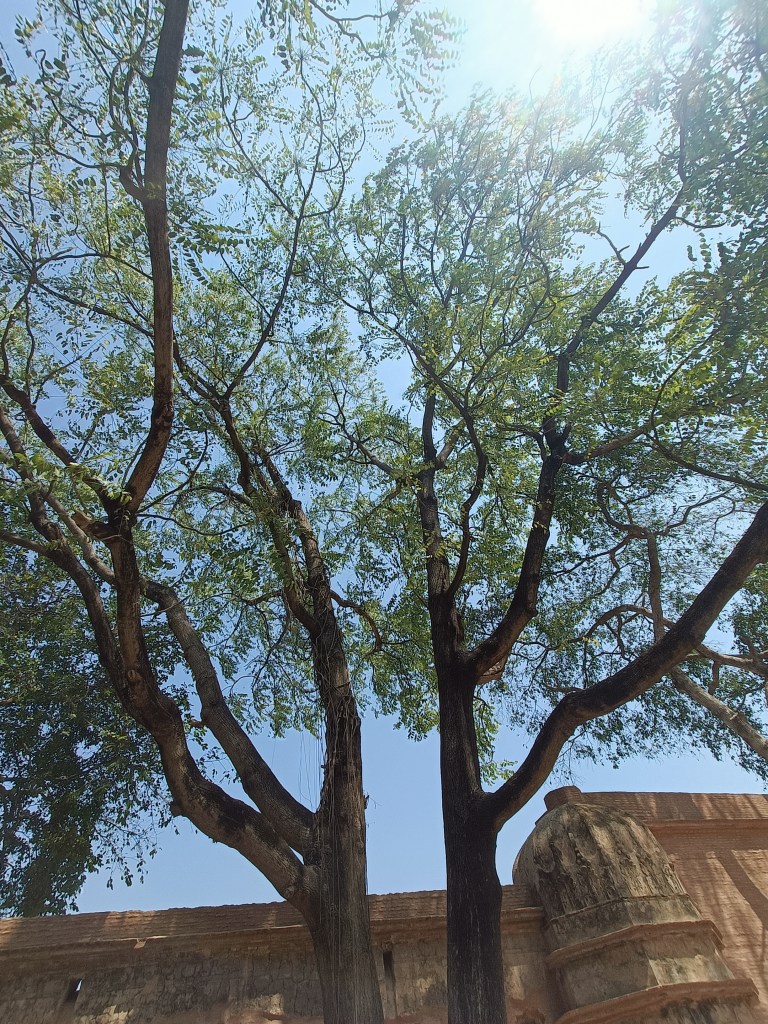

We walk around and behold the sunshine. Pigeons make their passage like unobtrusive guides. It’s once we enter the main hall of the Imambara that its richness finds heft and visual import. Intricate doorways in black open the way to the sanctum where colours shimmer and add lustre to portraits of erstwhile kings.

Here tazias (handmade religious symbols), chandeliers, gilded mirrors and clocks, tapestries, lanterns, Quranic verses engraved on walls and pillars evince an aura of holding everything in a single space. Yet they never overwhelm the assortment. From the high roof with circular vents, light floods this space as green and gold filigrees shimmer admiration for the craft. Gold, green, black, white are the prominent colours expediting a unique spiritual leadership. We come here to capture serenity in our pulses, quieting our anxious throb. Shah Najaf Imambara commences that sojourn in true humbling fashion. It’s said that the thick walls around the central mosque withstood the heavy gun fires of the Rebellion of 1857. Looking at this centre of secularism today, it’s obvious there’s some extraordinary strength that still radiates power and integrity.

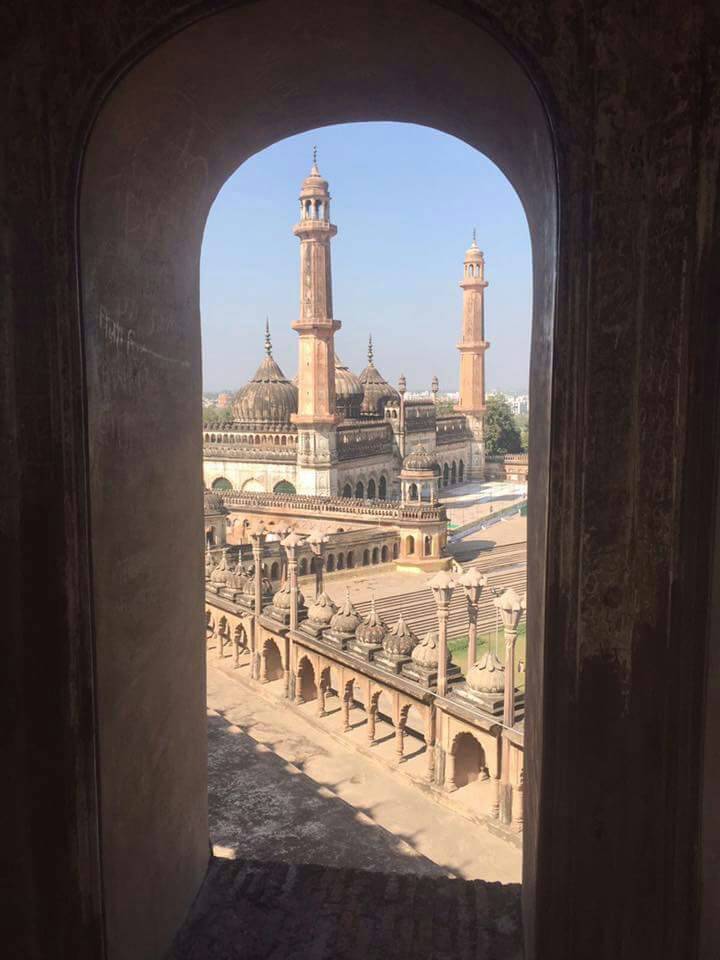

Then walking towards the further center of Hazratganj which is bustling and still lively with the rhythms of an active day, we reach the other spiritual cousin which is the Sibtainabad Imambara. Here too, dual gateways, one that begins amid the main market area and the other that leads us further to the main structure, are attractions in their own individual right. Then commanding a centre surrounded by a few residences styled in an exquisite classical style is a white mosque, Sibtainabad Imambara, raised on an eight-foot platform navigated by steps. Its historical continuum is still intact and that is why it’s so fascinating.

It was Amjad Ali Shah(1801-1847), the fourth King of Awadh, who greenlit its construction as a place of majlis (mourning) in memory of Imam Hussain’s martyrdom in the Battle of Karbala. It was his son, the great Wajid Ali Shah, who completed the structure with his army of architects and other creative hands. Today, Sibtainabad Imambara houses Amjad Ali Shah’s tomb and bears the history of being under the eye of the storm during 1857. But since History and Time always have a unique way of restoring Lucknow’s architectural marvels, it has withstood the test of time despite changing administrative jurisdictions and the gradual passage of eras.

Its outer surface is one of arches, parapets, eaves, dome and stucco which makes it conjoin its formation with Shah Najaf Imambara. The interiors are adorned with beautiful green paint of the most impressive hue. The main hall enthralls with images of horses bearing coat of arms, floral designs, anthropomorphic beings, swords, angels harking to past riches and fish symbols central to the city. Stained glass windows, huge mirrors on the walls and chandeliers complete a mosaic of colours that take the caravan of spiritual fulfillment further ahead, all the way from Shah Najaf Imambara.

Tazias deck the main hall while a throne shrouded in black and zig-zagging floor designs create a most exquisite picture.

While many people, men and women say their prayers here in both these places of spirituality, religious exclusivity never even becomes a point of consideration. You can be anyone, belonging to any faith or religious background which are after all man-made labels. Both the Shahnajaf and Sibtainabad Imambaras let us become one with the light emanating from their natural structures and the tranquil air that counters the world of noise and everyday activity. We are encased or should we say delivered from the coves of our daily occupations to their cores of transformation simply by choosing to go there.

Spirituality and faith beckon private, internalised journeys. Both the Shahnajaf Imambara and Sibtainabad Imambara attest to those journeys, occupying the heart of Lucknow to let its bloodstream flow with due diligence, with an eye towards true serenity.

.

Prithvijeet Sinha is an MPhil from the University of Lucknow, having launched his prolific writing career by self-publishing on the worldwide community Wattpad since 2015 and on his WordPress blog An Awadh Boy’s Panorama. Besides that, his works have been published in several journals and anthologies.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International