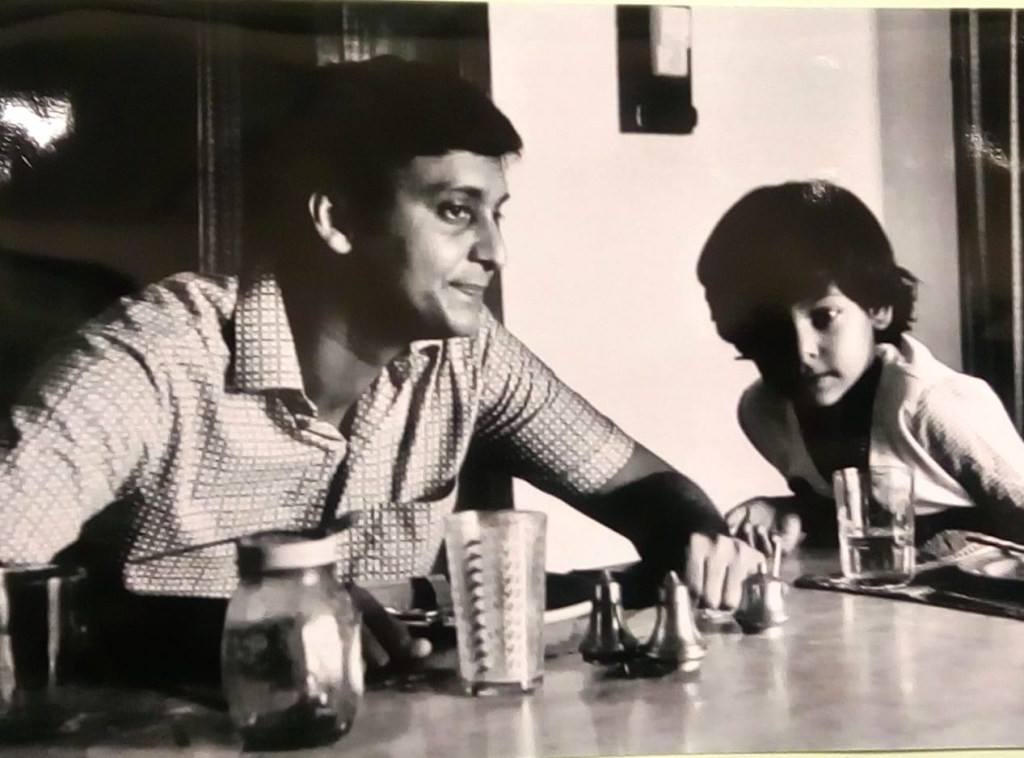

Poulami Bose Chatterjee converses with Ratnottama Sengupta

“All the recovery Rono Bhaitu[1]( Soumitra’s grandson) has made, is entirely due to his mother,” Soumitra Chatterjee (1935-2020) had said to me when I met him before Covid set in. His voice was laden with deep affection and paternal pride for his daughter. Deservedly so, as the world has been witnessing since the star actor passed away in November 2020. Poulami took upon herself the male mantle of lighting her father’s pyre.

But that was neither the beginning nor the end of her duty towards her father. I had seen her perform on stage alongside the thespian in Homapakhi [A Legendary Bird] that had explored the complexities of a society trying to reconcile its modern aspirations with traditional roots.

And last November she directed Janmantar [Rebirth], an original play Soumitra Chatterjee had written in 1993 but was never staged before. Seen through the eyes of a matinee idol who is visiting a remote village in Purulia, it focused on ills like child marriage, witch hunting, clash between and land owners and cultivators. “Unfortunately, 30 years later too, all the ills are still thriving on that soil,” Poulami said to me.

And in January, even as the definitive biography Soumitra Chatterjee and his World was being launched in the Kolkata Literary Meet, she staged Chandanpurer Chor [The Thief of Chanderpur], his light hearted transliteration of Jean Anouilh’s Carnival of Thieves[2], to mark his birth anniversary.

On the eve of the International Women’s Day I conversed with Poulami, whose parents have been an integral part of my life too.

Ratnottama Sengupta: Who is Poulami? A Bharatanatyam dancer? A theatre person? Mother of an actor with a brief trajectory? Or, daughter of Soumitra Chatterjee?

Poulami Bose: I think Poulami is a bit of all this — along with a passionate theatre practitioner. I am my mother’s daughter too. I hope I am a loyal friend to my friends. But above all I’m myself. I like to think of myself as a free spirit — absolutely totally in love with my daughter and son and music and dance and theatre and all that is wonderful in the world.

RS: When did you first realise that your father was not a 10-5 pm office going father like that of other girls? That he was a star?

PB: For a long time in my growing up years I actually didn’t realise how big a star he was. He was a very loving, hands-on father, very involved in our lives. I always knew he was an actor but didn’t realise the magnitude of his stardom. He never brought that aspect home. Our home was always filled with lively discussions, about books, music, paintings, dance, theatre, cinema, the environment, travel… It was a beautiful childhood, very loving, very secure.

Bapi [father] and Ma were always introducing us to new things. Encouraging us to embrace the world. I thought that was normal and that’s what every father was like. Only after I grew up did I realise his impact on the Bengali moviegoers’ lives.

RS: What did a ‘cine star’ mean to you when a) you were learning Bharatanatyam under Thankamani Kutty? b) Studying? c) Getting married to Ruchir Bose?

PB: The word ‘Cine Star’ didn’t matter much when I was learning dance or studying because I was treated just like any other student, by my teachers and my friends. In fact my father didn’t believe in the word ‘Star’. He maintained that he was a professional actor — and we were certainly not encouraged to have airs and graces about us. So we interacted normally with people, and people did likewise. Some people were of course star struck but they didn’t make a difference to me. As for getting married to Ruchir: he was and still is a very down to earth person, far removed from the film industry, very humane. He and his family have always accepted me and treated me for who I am rather than who my father was.

RS: Who was a bigger star for you — Soumitra Chatterjee or Satyajit Ray?

PB: Of course Satyajit Ray! Soumitra Chatterjee was my father first and then everything else, whereas Satyajit Ray was larger than life. We grew up hero worshipping him. Our whole family was absolutely in awe of him — as a person, as a filmmaker, an author and the rest. We were influenced a great deal by his way of life. His sensibilities. In fact we still idolize him.

RS: Which films of Soumitra Chatterjee have you loved most?

PB: Oh there are so many! Apur Sansar, Sansar Simante, Jhinder Bondi, Koni. Ekti Jiban, Dekha, Mayurakshi, Agradani, Ashani Sanket, Abhijan, Sonar Kella, Ganadevata, Atal Jaler Ahwan, Aparichita, Teen Bhubaner Pare, Baghini, Basanta Bilap, Shakha Prasakha, Charulata, Kapurush, Akash Kusum, Dwando, Borunbabur Bondhu…[3] I can go on.

The most impressive thing for me was his versatility. He was different in all the films that I have mentioned above. He was one actor who didn’t have mannerisms. He always became the character. I have seen him doing a lot of homework, research to delve deep into the character’s psyche. Acting was his passion and that was evident in whichever role he played.

RS: Which film of your father has impacted you most? One that moved you at a personal level, perhaps because you identified with it most?

PB: I think Koni. His now iconic dialogue, “Fight Koni, fight!” has stayed with me till this day. Whenever I feel low or face any kind of obstacle, I always remember him in the film. How the human spirit is capable of rising against all odds. How hard work and determination can carry you forward. It inspires not to give up without a fight.

RS: Soumitra Da was a Master in Bengali; Deepadi[4] in English. Who guided you in your studies? Who selected what books you will read?

PB: My parents, like I said earlier, were hands on parents. They, both, helped me with my school work. The atmosphere in our house revolved around books, so we read a lot while growing up. Ma had done her MA in Philosophy. She and Bapi introduced me to both English and Bengali literature. Bapi was more strict, he expected me to read classics and serious books. Ma was more liberal, she let me read anything I wanted to, including romance novels which my father thought were a waste of time.

RS: So who are your favourite authors?

PB: I am eclectic in my choice. I read classics as well as bestsellers, plenty of them. My favourite authors are Tarashankar Bandopadhyay, Bibhuti Bhushan, Manik Bandopadhyay, Jibanananda Das, Shakti Chattopadhyay, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Charles Dickens, O Henry, Oscar Wilde, Maupassant, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, Samaresh Basu, John Grisham, Pablo Neruda, Gabriel García Marquez, Arundhati Roy, Agatha Christie, Akhtaruzzaman Elias, Humayun Ahmed, Jeffrey Archer, Khaled Husseini, Chitra Divakaruni Banerjee, Satyajit Ray, Sukumar Ray, Saradindu Bandopadhyay, Paolo Coelho, Gerald Durrell, Charlotte Bronte, Emily Bronte, Lewis Carroll… to name a few!

RS: Soumitra Da was a poet. He also translated plays — classics of world theatre — into Bengali. What was he most happy to do — act in movies? Write and direct plays? Or retire to the inner world of poetry?

PB: All three. I’ve never seen him sit idle or waste time. It depended on his mood — he loved doing all three. But I must add: theatre was, always, his first love. He was deeply influenced by Sisir Bhaduri (1889-1959), with whom he had started out. He directed plays for Pratikriti, a group that Ma had — and he directed plays for Abhinetri Sangha, set up by the actors of Tollygunge.

RS: Deepadi was an ace badminton player. Did she give up her own world to be Mrs Soumitra Chatterjee?

PB: She gave up her career primarily for us. Bapi was at the peak of his career and was naturally very busy. Ma felt we needed to have at least one parent around, always. In retrospect, I realise it was a huge sacrifice. But I have to say, both my brother and I needed her. I think she realised that and did what most mothers do: she prioritized us over her career.

Ma had the biggest heart ever. She was more intelligent than the three of us put together. And she was non-judgmental about who she was reaching out to. So many sportswomen she helped, on her own. And I vividly remember this young Muslim boy in New Market who always carried her shopping to the car. One day Ma learnt that he had TB. She immediately brought him home and organised a room on the terrace for him to stay until he recovered. She didn’t hesitate because she had children, she didn’t seek the advice of doctors, she didn’t think twice because her husband was a star!

RS: Why did you choose to carry forward Soumitra Chatterjee’s legacy on stage rather than on screen?

PB: Theatre kind of seeped into me. I used to watch Bapi – when he was idling, he would arrange the empty cigarette and matchboxes to design sets. I have been on stage ever since I could walk. It is my first love. I’m passionate about live performances, be it dance or theatre. Not that I didn’t get offers for films but I never actively pursued them. I married relatively early and had both my children by the time I was 26. Stage was always more accommodating and easier to manage. And till now the magic of the stage hasn’t worn off. I am still madly in love with the stage. Screen just didn’t happen… no particular reason, really.

RS: Soumitra Da was proud of his grandson’s screen presence. And he was extremely proud of the manner in which you handled your son’s unfortunate accident. Would you like to talk about it?

PB: Bapi had high hopes for Ronodeep. He felt Rono was a very sensitive actor perfectly suited for the screen. He was devastated by Rono’s accident. It was the most tragic thing to have happened in all our lives. But I have come to terms with it. I count my blessings — it could have been worse! Rono is with us — a bright and wonderful boy, sensitive and sweet, full of love and empathy. He still has a long way to go in terms of recovery and health but he’s getting there, one step at a time…

I have learned a lot from this phase of my life. I continue to learn every day. It has also shaped me, moulded me as a person. Bapi-Ma told me always to have grace even under pressure, to be always dignified. I have tried to follow them.

RS: Can you recount one cherished moment with your father?

PB: In May 2020, months before he passed away, during Covid, Bapi and I were just sitting and talking about various things. Suddenly he told me, “Mitil I have never said this to you before but I want you to know that I am very proud of the way you have conducted yourself during Bhaitu’s accident and every day since then. Your dignity and your grace has made me really happy. I’m so proud that you have turned out to be the person you are!”

All through my life I will cherish this one moment.

RS: In today’s world many daughters are taking up the responsibility of carrying forward the legacy of their fathers. What, in your opinion, has brought about this social change? Did Soumitra Chatterjee raise you to (consciously) fight patriarchy?

PB: I guess the world is waking up to the fact that what sons can do, daughters can do better! I really don’t know what exactly has brought this social change but I definitely welcome it. My daughter is a great source of strength for me. She is my best friend. My father had raised my brother, Sougata, and me as equals, maybe favouring me a tad more!

Bapi was always ahead of his times. He always told me, “The sky is the limit, you can do whatever you set your mind to.” But it was Ma who very consciously taught me to fight patriarchy. She was a champion for the girl child.

RS: Soumitra Da was never lured by the reach and fame of Bollywood? So, why did he direct Stree Ka Patra[5], the telefilm he made for the national television, in Hindi?

PB: Bapi believed that he could deliver best in his own mother tongue. Besides, he was not enamoured of the kind of films made in Bollywood at that time. He loved his life here, his theatre, his poetry, and co-editing Ekshan, the culture magazine that first published Satyajit Ray’s script. Going to Bollywood, he felt, would put a stop to all his literary and theatrical pursuits.

However, he got the offer to direct Stree Ka Patra for National Doordarshan, and it came with the clause that it had to be in Hindi. The other telefilm he directed, Mahasindhur Opar Theke [ From the Other side of the Ocean] was in Bengali

RS: Many uncharitable people say that Soumitra Chatterjee wasted his talent by limiting himself to Bengali films and by indiscriminate selection of roles — because of his family responsibilities. Your response to this?

PB: Limiting himself to Bengali films was a conscious decision he made. And I have just elucidated the reasons. Yes he wanted to provide for his family, and he did so the only way he knew to — by acting. He never shied from saying that he was a professional actor. And if he wanted to take on the responsibilities who is anyone else to talk about it?

He could have abandoned his family like many others. He chose not to. His family, his life, his choices… that’s all I can say.

RS: You have grown up in close proximity with stars like Sharmila Tagore, Madhabi Mukherjee, Sandhya Roy, Tanuja, and directors like Tapan Sinha, Ajoy Kar, Tarun Majumdar, Rituparno Ghosh. Please share some memories/ anecdotes with us.

PB: The only name in the list who I have grown up in close proximity with is Tapan Sinha, whose birth centenary is being celebrated. He was a wonderful human being! While we were growing up we didn’t interact much with people from the film industry. We certainly met them but at parties, weddings, social events…

My parents had a huge circle of friends. A doctor’s group. My mum’s friends. Poets like Shakti Kaku and Sunil Kaku. My dad’s friends like Nirmalya Acharya, the co-editor of Ekshan. Directors Ajit Lahiri, Ashutosh Mukherjee, Nripen Ganguly who was fondly called ‘Nyapa Da.’ Friends from theatre. His childhood friends. It was a vast cross section of people, so it was wonderful, happy and great fun growing up around so many amazing people.

RS: Gaachh [Tree], the documentary by Catherine Berger, focused only on his stage life. Abhijan[6][The Expedition] directed by renowned actor Parambrata Chatterjee, did not excite cineastes who have adored Soumitra Chatterjee, honoured with Dadasaheb Phalke for cinema, Sangeet Natak award for theatre, decorated with the Lotus award of Padma Bhushan and the French Order des Arts et des Lettres. Will you give us a biopic of Soumitra Chatterjee on stage?

PB: I am not in favour of a biopic for someone like Bapi. On the other hand, a stage production would be limiting. He was a multihued talent. It is difficult to capture so many facets of his personality. It is a daunting task to encompass every nuance, every shade of such an extraordinary life in a single film. A biopic should not be made if it does not do justice to the magnificence of the man.

.

[1] Ronodeb Bose, grandson of Soumitra Chatterjee, had a bike accident in 2017

[2] Jean Anouilh (1910-1987), Carnival of Thieves(1938)

[3] Bengali films in which Soumitra Chatterjee played the lead.

[4] Deepa Chatterjee, wife of Soumitra Chatterjee

[5] A pun in the heading. Stree is woman, Patra is vessel as well as a prospective groom. So, a Woman’s Vessel or Prospective Groom

[6] Soumitro Chatterjee played the lead in the 1962 Abhijan, directed by Satyajit Ray

.

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International