Book Review by Rakhi Dalal

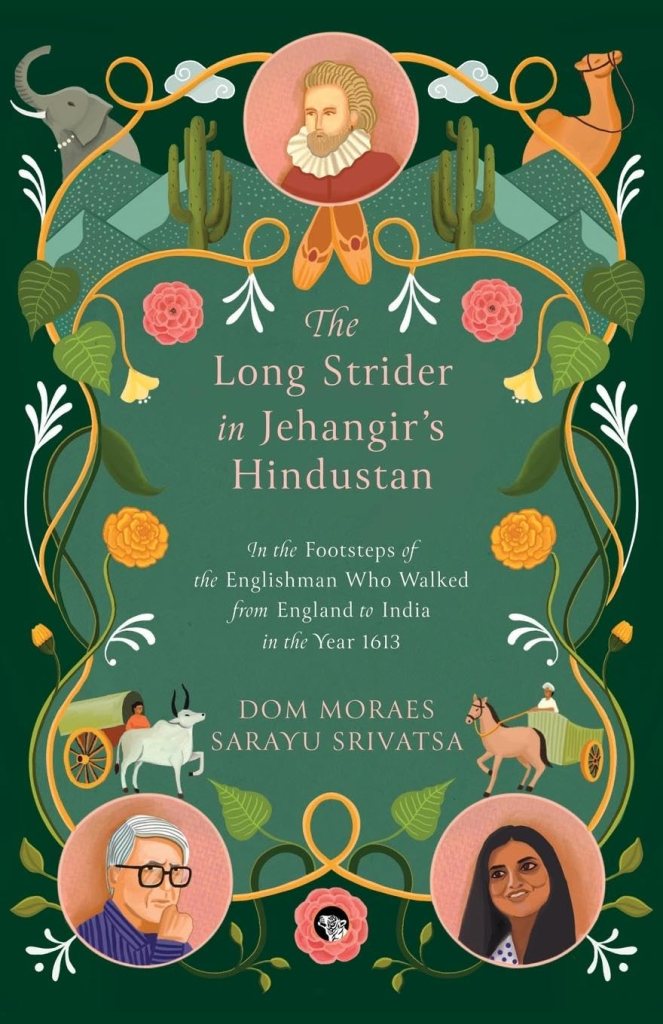

Book Title: The Long Strider in Jehangir’s Hindustan: In the Footsteps of the Englishman Who Walked From England to India in the Year 1613

Authors: Dom Moraes and Sarayu Srivatsa

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

During the years, in the early seventeenth century, when East India Company began a search for the possibilities of trade with India via sea route, Thomas Coryate of the village Odcombe in Somerset, England, made an ambitious plan to travel to the Indies, as he called it, on foot. This wasn’t his first undertaking. Having travelled across Europe on foot before, writing a travelogue Crudities on his experience which brought him some fame, he now wished to travel to a place no Englishmen had gone before. Motivated by the thought of gaining more fame with this venture so as to win the affection of Lady Ann Harcourt of Prince Henry’s Court, even the idea of traversing 5000 miles on foot as compared to 1975 miles that he did in Europe did not dissuade him.

Known as ‘the long strider’, in 1612, Coryate set for his journey to the Indies from London. And in year 1999, more than three hundred years later, his journey and subsequent struggles, somehow inspired Dom Moraes to traverse the same route to correlate Coryate’s experience in the now altered places and its people. Coryate travelled alone, Moraes took the journey with Sarayu Srivatsa, the co-author of this book.

Dom Moraes, poet, novelist and columnist, is seen as a foundational figure in Indian English Literature. He published nearly thirty books in his lifetime. In 1958, at the age of twenty, he won the prestigious Hawthornden Prize for poetry. He was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for English in 1994. The Long Strider in Jehangir’s Hindustan was first published in the year 2003. Moraes passed away in 2004.

Sarayu Srivatsa, trained as an architect and city planner at the Madras and Tokyo universities, was a professor of architecture at Bombay University. Her book, Where the Streets Lead, published in 1997 had won the JIIA Award. She also co-authored two books with Dom Moraes: The Long Strider, and Out of God’s Oven (shortlisted for the Kiriyama Prize). Her first novel, The Last Pretence, was longlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize, and upon its release in the UK (under the title If You Look For Me, I am Not Here), was also included on The Guardian’s Not the Booker Prize longlist.

Srivatsa, who travelled with Moraes to all the places Coryate passed through, writes diary chapters coextending the same routes subsequently. So, each fictive reconstruction of a period and place of Coryate’s travel by Moraes is followed by a diary chapter for the same place by Srivatsa. In that sense the book becomes part biographical fiction and part memoir.

Coryate, son of a Vicar and dwarfish in stature, was seized by this desire to gain fame and respect. What desire seized the imagination of Moraes, eludes this reader. It, however, doesn’t escape the notice that both the writers shared somewhat similar plight towards the end.

Some of Coryate’s writing during the period did not survive as it was destroyed by Richard Steele, but the rest was sent to England and was posthumously published in an anthology in 1625. Basing his research on such sources, after extensive three years of investigation, Moraes managed to create an account of Coryate’s demeanour, his lived life in a new land with diverse people and customs at different places which he found both shocking and fascinating. Coryate found the people of India loud and violent but he was also touched by their generosity and kindness. He witnessed the disagreements between Hindus and Muslims, the caste system where the upper caste oppressed the people from lower caste, sati, and the ways of Buddhist monks, Sikhs, pundits of Benaras and Aghoris[1], the lifestyle of Jehangir and the city of Agra before Taj Mahal. He was fortunate to have an audience with Jehangir, the main reason of his travel, but he failed in securing his patronage or enough money to continue to China which he had been his original intent.

In Moraes’ writing, the era comes alive. Vivid imagery and description makes the struggles and sufferings of Coryate palpable on one hand and on the other offer a view on the unfolding of history in a country where these many hundred years later, the echoes of a past similar to the present can be heard. In the preface, Moraes posits one of the reasons to take on the book — to compare the India then with the country during his times. As the reader proceeds with the story, the comparison becomes apparent in Moraes’ construction vis-a-vis Srivatsa’s entries.

Towards the end, an ailing Coryate succumbed to his illness and his body was buried somewhere near the dock at Surat. He could not make a journey home in 1615, but in 2003 a brick from his supposed tomb was sent back to the church in Odcombe by Srivatsa where a ninety six year old vicar waited patiently for the only famous man from Odcombe to return home. The epilogue by Srivatsa gives an account of Moraes’ own struggle with cancer and his demise in 2004, a year after the book was published. It is but right that the soil from his grave in Mumbai also found a resting place in Odcombe.

[1] Devotees of Shiva

Rakhi Dalal writes from a small city in Haryana, India. Her work has appeared in Kitaab, Scroll, Borderless Journal, Nether Quarterly, Aainanagar, Hakara Journal, Bound, Parcham and Usawa Literary Review.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International