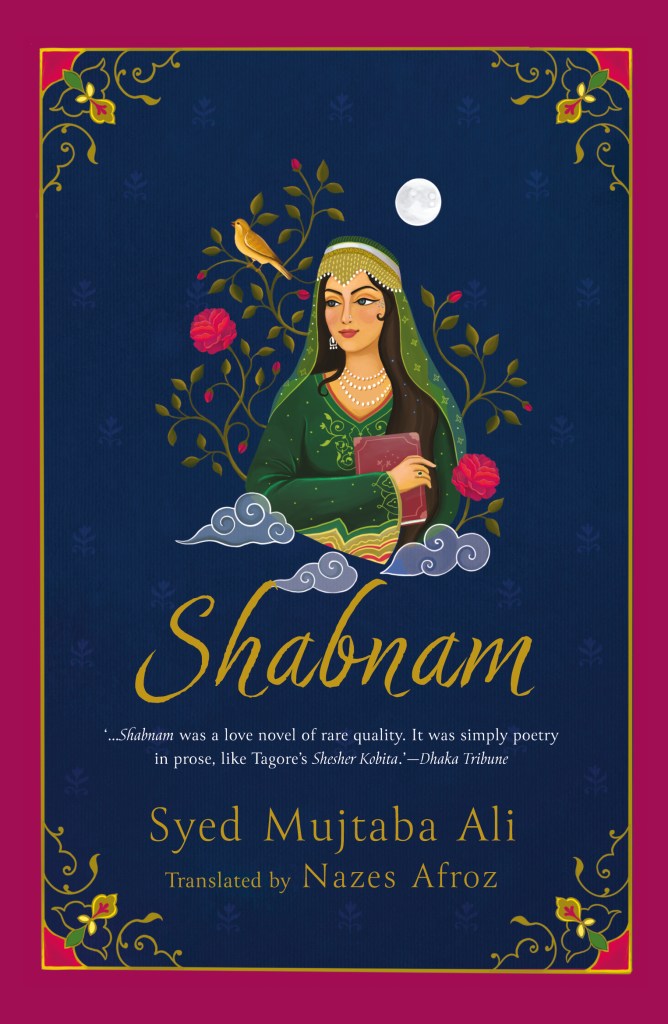

Title: Shabnam

Author: Syed Mujtaba Ali

Translated from Bengali by Nazes Afroz

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Badshah Amanullah was surely off his rocker. Or else why would he hold a ball-dance in an ultra-conservative country like Afghanistan? On the occasion of Independence Day, Afghanistan’s first ball-dance would be held.

We, the foreigners, were not that bothered. But there was a buzz of restlessness among the mullahs and their followers—the water carriers, tailors, grocers, and the servants. My servant, Abdur Rahman, while serving the morning tea, muttered, ‘Nothing is left of religious decency.’

I did not pay much heed to Abdur Rahman. I was no messiah like Krishna. The task of saving ‘religious decency’ had not been bestowed upon me.

‘Those hulking men will prance around the dance floor holding on to shameless women.’

I asked, ‘Where? In films?’

After that there was no stopping Abdur Rahman. The ancient Roman wild orgies would have sounded like child’s play compared to the juicy imageries of the upcoming dance event that he described. Finally, he concluded, ‘Then they switch off the lights at midnight. I don’t know what happens after that.’

I said, ‘What’s that to you, you mindless babbler?’

Abdur Rahman went mum. Whenever I called him a blathering prattler, he understood that his master was in a bad mood. I would use the Bengali slang word for it and being a seasoned man, though Abdur Rahman did not know the language, he would be able to read my mood.

I was out in the mild evening. Electric lamps lit up the bushes of Pagman. The tarmacked road was spotlessly clean. I was meandering absentmindedly, thinking it was the month of Bhadra and Sri Krishna’s birthday had been celebrated the previous day. My birthday too, according to Ma. It must be raining heavily in Sylhet, my home. Ma was possibly sitting in the north veranda. Her adoptive daughter Champa was massaging her feet and asking her, ‘When will young brother come home?’

The monsoon season is the most difficult one for me in this foreign land. There is no monsoon in Kabul, Kandahar, Jerusalem or Berlin. Meanwhile in Sylhet, Ma is flustered with the nonstop rain. Her wet sari refuses to dry; she is in a tizzy from the smoke of the wet wood of the oven. Even from here I can see the sudden pouring of rain and the sun that comes out after a while. There are glitters of happiness on the rose plants in the courtyard, the night jasmine at the corner of the kitchen, and on the leaves of the palm tree in the backyard.

There was no such verdant beauty here.

Look at that! I had lost my way. Nine at night. Not a soul on the street. Who could I ask for directions?

A band was playing dance numbers in the big mansion to the right.

Oh! This was the dance-hall as described by Abdur Rahman. The waiters and bearers of the building would surely be able to direct me to my hotel. I needed to go to the service doors at the back of the building.

I approached.

Right at that moment, a young woman marched out.

I first saw her forehead. It was like the three-day-old young moon. The only difference was the moon would be off-white—cream coloured—but her forehead was as white as the snow peaks of the Pagman mountains. You have not seen it? Then I would say it was like undiluted milk. You have not seen that either. Then I can say it was like the petals of the wild jasmine. No adulteration of it is possible as yet.

Her nose was like a tiny flute. How was it possible to have two holes in such a small flute? The tip of the nose was quivering. Her cheeks were as red as the ripe apples of Kabul; yet they were of a shade that made it abundantly clear it was not the work of any rouge. I could not figure out if her eyes were blue or green. She was adorned in a well-tailored gown and was wearing high-heeled shoes.

Like a princess she ordered, ‘Call Sardar Aurangzeb Khan’s motor.’

Attempting to say something, I fumbled.

She, by then, looked properly at me and figured out that I was not a servant of the hotel. She also understood that I was a foreigner. First, she spoke in French, ‘Je veux demand pardon, monsieur—forgive me—’ Then she said it in Farsi.

In my broken Farsi I said, ‘Let me look for the driver.’

She said, ‘Let’s go.’

Smart girl. She would be hardly eighteen or nineteen.

Before reaching the parking lot, she said, ‘No, our car isn’t here.’

‘Let me see if I can arrange another one,’ I said.

Raising her nose an inch or so, in rustic Farsi she said, ‘Everyone is peeping to see what debauchery is taking place inside. Where will you find a driver?’

I involuntarily exclaimed, ‘What debauchery?’

Turning around in a flash, the girl faced me and took my measure from head to toe. Then she said, ‘If you’re not in a hurry, walk me to my house.’

‘Sure, sure,’ I joined her.

The girl was sharp.

Soon she asked, ‘For how long have you been living in this country? Pardon—my French teacher has said one shouldn’t put such questions to a stranger.’

‘Mine too, but I don’t listen.’

Whirling around she faced me again and said, ‘Exactment—rightly said. If anyone asks, say I’m going with you, or say Daddy introduced me to you. And don’t you ask me any question like I’m a nobody. And I will not ask anything as if you have no country or no home. In our land not asking prying questions is akin to the height of rudeness.’

I replied, ‘Same in my land too.’

She quipped, ‘Which country?’

I said, ‘Isn’t it apparent that I’m an Indian?’

‘How come? Indians can’t speak French.’

I said, ‘As if the Kabulis can!’

She burst out laughing. It seemed in the fit of laughter she suddenly twisted her ankle. ‘Can’t walk any longer. I’m not used to walking in such high heels. Let’s go to the tennis court; there are benches there.’

Dense darkness. The electric lamps were glowing far away. We needed to reach the tennis court through a narrow path. I said, ‘Pardon,’ as I touched her arm inadvertently.

Her laughter had no limits. She said, ‘Your French is strange, so is your Farsi.’

My young ego was hurt. ‘Mademoiselle!’

‘My name is Shabnam.’

(Extracted from Shabnam by Syed Mujtaba Ali, translated by Nazes Afroz. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2024)

About the Book

Afghanistan in the 1920s. A country on the cusp of change. And somewhere in it, a young man and woman meet and fall in love.

Shabnam is an Afghan woman, as beautiful as she is intelligent. Majnun is an Indian man, working in the country as a teacher. Theirs is an unlikely love story, but it flowers nonetheless. Breaking the barriers of culture and language, the two souls meet. Shabnam is poetry personified—she knows the literary works of Farsi poets of different eras. Majnun is steeped in the language and thoughts of Bengal. Together, they find love in immortal words and in the wisdom of the ages.

As the country hurtles towards yet another cataclysmic change, and the ruling king flees into exile, Shabnam is in danger from those who covet her for her famous beauty. Can she save herself and her Indian lover and husband from them?

Shabnam has been hailed as one of the most beautiful love stories written in Bengali. Lyrical and tragic, this pathbreaking novel appears in English for the first time in an elegant translation by the translator of Syed Mujtaba Ali’s famous travelogue Deshe Bideshe (In a Land Far from Home).

About the Author

Born in 1904, Syed Mujtaba Ali was a prominent literary figure in Bengali literature. A polyglot, a scholar of Islamic studies and a traveller, Mujtaba Ali taught in Baroda and at Visva-Bharati University in Shantiniketan. Deshe Bideshe was his first published book (1948). By the time he died in 1974, he had more than two dozen books—fiction and non-fiction—to his credit.

About the Translator

A journalist for over four decades, Nazes Afroz has worked in both print and broadcasting in Kolkata and in London. He joined the BBC in London in 1998 and spent close to fifteen years with the organization. He has visited Afghanistan, Central Asia and West Asia regularly for over a decade. He currently writes in English and Bengali for various newspapers and magazines and is working on a number of photography projects.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL