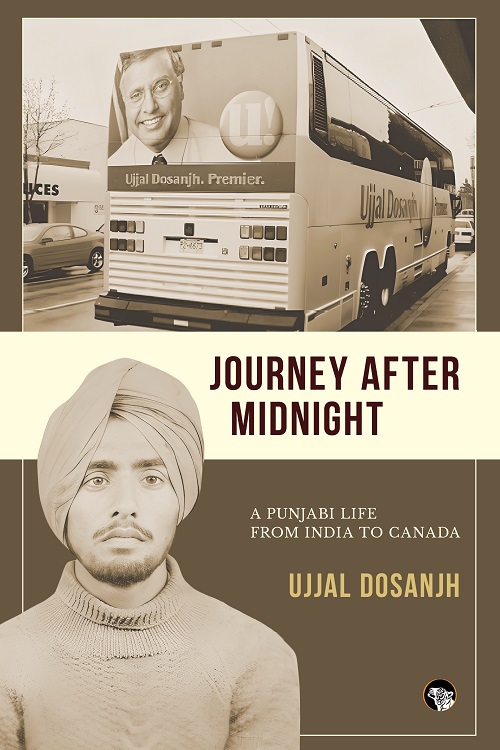

Title: Journey After Midnight: A Punjabi Life from Canada to India

Author: Ujjal Dosanjh

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

50

A variation on the common Indian expression “Mullan de daur maseet taeen,” which roughly translates as “An imam’s ultimate refuge is the mosque,” sums up my relationship with the world: India is my maseet. I have lived as a global citizen, but India has been my mandir, my masjid, and my girja: my temple, my mosque, and my church. It has been, too, my gurdwara, my synagogue, and my pagoda. Canada has helped shape me; India is in my soul. Canada has been my abode, providing me with physical comforts and the arena for being an active citizen. India has been my spiritual refuge and my sanctuary. Physically, and in the incessant wanderings of the mind, I have returned to it time and again.

Most immigrants do not admit to living this divided experience. Our lack of candour about our schizophrenic souls is rooted in our fear of being branded disloyal to our adopted lands. I believe Canada, however, is mature enough to withstand the acknowledgement of the duality of immigrant lives. It can only make for a healthier democracy.

Several decades ago, I adopted Gandhi’s creed of achieving change through non-violence as my own. As I ponder the journey ahead, far from India’s partition and the midnight of my birth, there is no avoiding that the world is full of violence. In many parts of the globe, people are being butchered in the name of religion, nationalism and ethnic differences. Whole populations are migrating to Europe for economic reasons or to save themselves from being shot, beheaded or raped in the numerous conflicts in the Middle East and Africa. The reception in Europe for those fleeing mayhem and murder is at times ugly, as is the brutal discrimination faced by the world’s Roma populations. The U.S. faces a similar crisis with migrants from Mexico and other parts of South America fleeing poverty and violence, in some cases that of the drug cartels. Parents and children take the huge risk of being killed en route to their dreamed destinations because they know the deathly dangers of staying. Building walls around rich and peaceful countries won’t keep desperate people away. The only lasting solution is to build a peaceful world.

Human beings are naturally protective of the peace and prosperity within their own countries. A very small number of immigrants and refugees, or their sons and daughters, sometimes threaten the peace of their “host” societies. But regardless of whether the affluent societies of western Europe, Australia, New Zealand and North America like it or not, the pressure to accept the millions of people on the move will only mount as the bloody conflicts continue. Refugees will rightly argue that if the West becomes involved to the extent of bombing groups like ISIS, it must also do much more on the humanitarian front by helping to resettle those forced to flee, be they poverty-driven or refugees under the Geneva Convention. With the pressures of population, poverty and violence compounded by looming environmental catastrophes, the traditional borders of nation states are bound to crumble. If humanity isn’t going to drown in the chaos of its own creation, the leading nations of the world will have to create a new world order, which may involve fewer international boundaries.

In my birthplace, the land of the Mahatma, the forces of the religious right are ascendant, wreaking havoc on the foundational secularism of India’s independence movement. I have never professed religion to be my business except when it invades secular spaces established for the benefit of all. Extremists the world over—the enemies of freedom—would like to erase both the modern and the secular from our lives. Born and bred in secular India, and having lived in secular Britain and Canada, I cherish everyone’s freedom to be what they want to be and to believe what they choose to believe.

I have always been concerned about the ubiquitous financial, moral and ethical corruption in India, and my concern has often landed me in trouble with the rulers there. Corruption’s almost complete stranglehold threatens the future of the country while the ruling elite remain in deep slumber, pretending that the trickle of economic development that escapes corruption’s clutches will make the country great. It will not.

Just as more education in India has not meant less corruption, more economic development won’t result in greater honesty and integrity unless India experiences a cultural revolution of values and ethics. The inequalities of caste, poverty and gender also continue to bedevil India. Two books published in 1990, V.S. Naipaul’s India: A Million Mutinies Now and Arthur Bonner’s Averting the Apocalypse, sum up the ongoing turmoil. A million mutinies, both noble and evil, are boiling in India’s bosom. Unless corruption is confronted, evil tamed, and the yearning for good liberated, an apocalypse will be impossible to avert. It will destroy India and its soul.

On the international level, the world today is missing big aspirational pushes and inspiring leaders. Perhaps I have been spoiled. During my childhood, I witnessed giants like Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew of the Indian freedom movement take their place in history and even met some of them. As a teenager, I was mesmerized by the likes of Nehru and John F. Kennedy. I closely followed Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy as they wrestled with difficult issues and transformative ideas. I landed in Canada during the time of Pierre Trudeau, one of our great prime ministers. Great leaders with great ideas are now sadly absent from the world stage.

The last few years have allowed me time for reflection. Writing this autobiography has served as a bridge between the life gone by and what lies ahead. Now that the often mundane demands of elected life no longer claim my energies, I am free to follow my heart. And in my continuing ambition that equality and social justice be realized, it is toward India, the land of my ancestors, that my heart leads me.

Extracted from the revised paperback edition of Journey After Midnight: A Punjabi Life from Canada to India by Ujjal Dosanjh. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2023.

About the Book: Born in rural Punjab just months before Indian independence, Ujjal Dosanjh emigrated to the UK, alone, when he was eighteen and spent four years making crayons and shunting trains while he attended night school. Four years later, he moved to Canada, where he worked in a sawmill, eventually earning a law degree, and committed himself to justice for immigrant women and men, farm workers and religious and racial minorities. In 2000, he became the first person of Indian origin to lead a government in the western world when he was elected Premier of British Columbia. Later, he was elected to the Canadian parliament.

Journey After Midnight is the compelling story of a life of rich and varied experience and rare conviction. With fascinating insight, Ujjal Dosanjh writes about life in rural Punjab in the 1950s and early ’60s; the Indian immigrant experience—from the late 19th century to the present day—in the UK and Canada; post-Independence politics in Punjab and the Punjabi diaspora— including the period of Sikh militancy—and the inner workings of the democratic process in Canada, one of the world’s more egalitarian nations.

He also writes with unusual candour about his dual identity as a first-generation immigrant. And he describes how he has felt compelled to campaign against discriminatory policies of his adopted country, even as he has opposed regressive and extremist tendencies within the Punjabi community. His outspoken views against the Khalistan movement in the 1980s led to death threats and a vicious physical assault, and he narrowly escaped becoming a victim of the bombing of Air India Flight 182 in 1985. Yet he has remained steadfast in his defence of democracy, human rights and good governance in the two countries that he calls home—Canada and India. His autobiography is an inspiring book for our times.

About the Author: Ujjal Dosanjh was born in the Jalandhar district of Punjab in 1946. He emigrated to the UK in 1964 and from there to Canada in 1968. He was Premier of British Columbia from 2000 to 2001 and a Liberal Party of Canada Member of Parliament from 2004 to 2011. In 2003 he was awarded the Pravasi Bharatiya Samman, the highest honour conferred by the Government of India on overseas Indians.

Click here to read the interview with Ujjal Dosanjh

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.