Ratnottama Sengupta converses with Reba Som

“If Washington goes to Dhaka, there’s a chance that Paris might make it to Stockholm. And of course Moscow would be moved to Geneva!?”

Sounds like gibberish? But this is a piece of the speculative conversation on transfers and postings that is regular in the drawing rooms of embassies and consulates, Dr Reba Som found out on her very first posting after her marriage with Himachal Som.

Both were Presidency graduates pursuing higher careers — he in Foreign Service, she on the threshold of a doctorate. But life as the wife of an ambassador wasn’t only about glamour postings, fancy holidays and brush with celebrities. It was a mixed bag of blessings, as the woman who had grown up in Kolkata with a grounding in Tagore’s music would soon conclude. For, there were the dark clouds of life away from ageing parents and school going children; from the comfort of familiar food and mastered language; from developing your potential and crafting your own identity in the world out there.

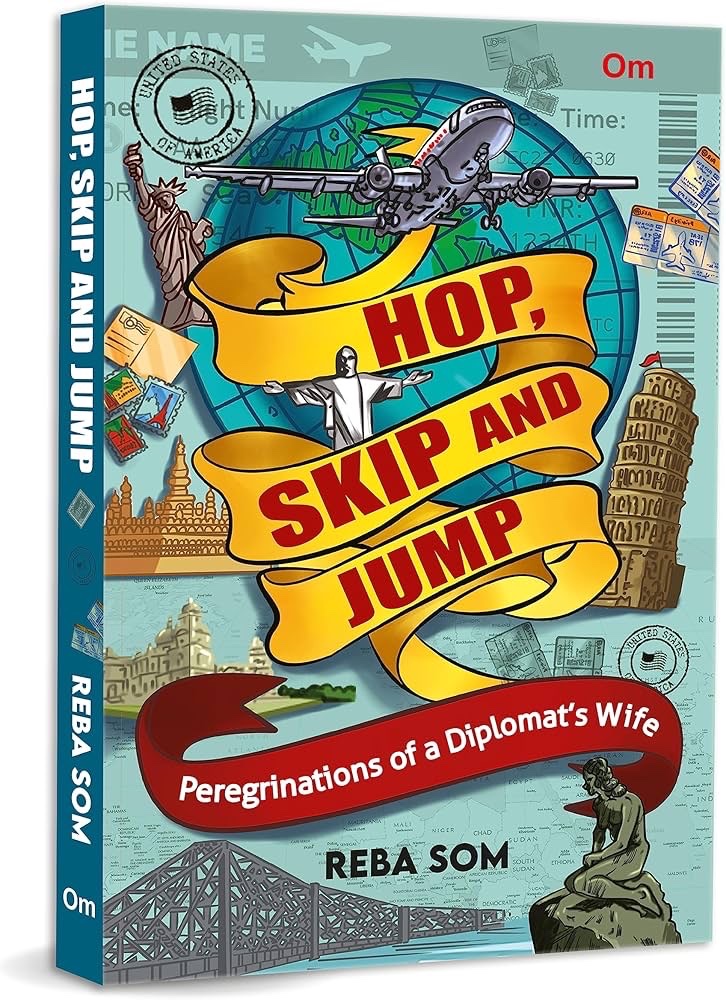

In recent years we have read accounts of retired ambassadors and career diplomats’ experiences in diplomatic life. In her memoirs, Hop, Skip and Jump; Peregrinations of a Diplomat’s Wife, Dr Som’s is a woman’s voice, abounding in stories and observations about how the spouses keep a brave front in alien surroundings to hold up the best image of her country. In this conversation, she voices outmore about her encounters with racism, with political emergencies and exigencies. In short, about her lessons in a borderless world of multicoloured humanity.

You went to Brazil (1972), then to Denmark (1974), then Delhi (1976), Pakistan (1978), New York (1981), Dhaka (1984), then Ottawa (1991), Laos (1994), Italy (2002). Please share your gleanings from these lands.

The roller coaster ride was a saga of discovery. Travelling across expanses of the planet earth that we had seen only on the pages of geography books and atlases was a great learning experience. I gained an understanding of diverse cultures, imbibed social customs, became proficient in languages, and was exposed to exotic cuisines. At the same time I faced homesickness. Each posting entailed the challenge of uprooting oneself, finding schools for children, and reinventing oneself every time.

A large part of this life was in the years that had no mobile phones, no video calls, no social media, no internet communication. What did you thrive on?

Continents and hemispheres away from home, the only link with family and friends then was the diplomatic bag. The weekly mail service ferried across oceans by the ministry in Delhi contained letters and parcels from home. We were asked to judiciously use the weight allowed to bring spices, tea, condiments, clothing and other necessities. It became a ritual to write long letters and send them weekly by the diplomatic bag to Delhi from where they would be posted to respective destinations throughout India.

Along with letters would come bundles of magazines and newspapers. These brought us news of home from which we were truly cut off. With no television or internet or phone calls, we were in the dark about all news, be it political, social or entertainment. Every week on the bag day we waited anxiously to receive the newspapers – and the letters, which had instructions, news, recipes, advice, gossip. All of these were crucial for nurturing our souls.

One telegram from my father in 1973 carried the cryptic message: ‘Reba, solitary First class.’ These were the MA results of Calcutta University which were out after a delay of two years.

I was most taken up by the understated humour of some of your encounters in your memoir. Please recount some of them.

On our very first posting, to Brazil, not only our unaccompanied baggage but also our accompanied baggage did not arrive. Eventually when the lost luggage showed up, Himachal’s ceremonial bandhgala[1]was steeped brown — in the colour of the gur[2] my mother had lovingly packed in!

In Brazil, we found the people to be fun loving but too flamboyant. They made tall claims that their institutions were the biggest in the world. But reality often proved the claims to be hollow. Such was the Presidential bid to make the tallest flag pole in the world in Brazil’s new capital, Brasilia. A very tall flag mast was indeed built but the huge flag atop it was torn to shreds since the engineers had not factored in the wind speed at that height. Brazilians mirthfully called it the President’s erection!

And at Denmark. we were surprised by a sudden news of our posting to Mozambique. We had long realised that we were mere players on the chessboard of postings – we could be shunted off across continents at the whims of the powers that be. By the same token, a couple of phone calls by the newly arrived ambassador undid the mischief. We were happy to unpack and settle down again. The only guilt I felt was when I met the owner of Anthony Berg chocolates: I had in no time demolished the entire carton of chocolates he had sent as farewell gift!

You are among the few I know who have mothered in different continents. So how different is it to become a mother away from India?

I always felt that the best way to get to know certain nuances of a country’s cultural tradition was to have babies in them. My elder son, Vishnu was born in Copenhagen and Abhishek, the younger one, in New York — and my experiences each time couldn’t be more different.

In Copenhagen, a social democrat country, hospital visits for full term pregnant women were fixed on a certain day of the week. On the preceding day they had to collect their urine in a jerry can and present it for lab examination. I was confounded and not a little embarrassed to meet other mothers-to-be, swinging their jerry cans like designer bags without fail on the appointed day. I learnt only later that, from the urine examination doctors would note the condition of the placenta and not unnecessarily rush patients into childbirth with caesarean and surgical intervention!

In NY, on the day of my discharge, the hospital staff were highly excited because Elizabeth Taylor had come in for one of her facelifts. I could not forgive them their magnificent obsession when, along with a goodbye hamper, they wheeled in a bassinet with a different baby. On my protestation the nurse rudely shouted, “Can’t you read… the tag says Som Junior?” Shocked by the implication I said, I could not only read but also see! And it was not my child. While everyone was looking on in disbelief another nurse wheeled in my little one. The babies had their diapers changed and were put back in the wrong bassinet.

Years later, we discovered in an informal meeting with an American ambassador that Abhishek was indeed an American citizen. Because, at the time of the child’s birth Himachal was posted not to the embassy in Washington but to the consulate in New York. Only consulate children were given the privilege. This discovery, rechecked by State Department Records, gave our son the US passport. It was a windfall as Abhishek went on to graduate summa cum laude from a prestigious management school in the US and enter Wall Street as an investment banker.

I must also share another truth about birthing away from India. Before Vishnu’s birth, my parents had come to Copenhagen. When I was discharged from the hospital I received their care and being fed Ma’s cuisine was the best gift I could have. So, when phone calls came from hospital, followed by visits enquiring about my state of depression, I was totally confused. I realised how many mothers suffered from postpartum depression in a society bereft of nurturing family care.

How could you master languages as removed as Portuguese from Lao and Italian from Urdu? Is a flair for languages the key to this proficiency or the training imparted before each posting?

I enjoy learning languages. My stint at learning French at Ramakrishna Mission Golpark stood me in good stead in grasping Portuguese in Brazil, French in Ottawa and Italian in Rome — all Latin languages. But there was also the hazard of mixing up some phrases and words, so similar yet so different! Like Bon Appetit in French and Bueno Appetito in Italian. Or Amor in Portuguese; amore in Italian and amour in French.

Sometimes though, I accidentally learnt how language travels. My mother had packed in many petticoats to match with my saris but without their cord. We went to a store that promised to hold all we need but all my sign language did not bring what I needed. “Phita is obviously not available here,” I told Himachal, preparing to leave. Suddenly the storekeeper perked up. ‘Fita, si senhora!” he said and produced bundles of cord.

In due time I found out that janala, kedara and chabi – Bengali for window, chair and keys – had travelled from India to become janela, cadeira and chavi.

What did Dhaka mean to one raised in West Bengal – per se the Ghoti-Bangal[3]divide, your roots or the cultural side with Firoza Begum and Nazrul Geeti?

Dhaka was a great posting in so many ways. It was a hop, skip and jump away from my home town Kolkata, with the same language and culture and yet was a foreign posting with foreign allowances!

As you know, there’s a subtle cultural difference in East and West Bengal. Both speak Bengali but in East Bengal, it’s a colloquial rustic dialect while West Bengal speaks its refined cultural form. This formed the infamous ‘Ghoti-Bangal’ divide: Urban Calcuttans looked askance at their country cousins from the East.

The difference extended to the palate. East Bengalis flavoured their dishes with more chillies and West Bengalis, with a pinch of sugar. For the fish loving people, the two iconic symbols are Hilsa and Prawns, for East and West. Emotions soared high in Kolkata when the supporters of the football teams, East Bengal and Mohun Bagan, clashed, after intensely fought matches that spurred deadly arguments and bets.

Given this background, Himachal created a minor storm by announcing to his parents from Chinsurah, Hooghly in West Bengal that he would marry a girl whose parents were from Dhaka and Faridpur in East Bengal. Ghoti-Bangal feud remained the subject of much friendly banter between Himachal and me until we were posted in Dhaka. There, in a diplomatic turnaround, Himachal played down his Ghoti background to announce that his mother’s family was from Chittagong and he was born in the principal’s bungalow in Daulatpur, Khulna, where his grandfather was posted.

To give a bit of Himachal’s family background: Dr Pramod Kumar Biswas, the first Indian doctorate in Agricultural Sciences from Hokkaido University in Japan, had settled in Dhaka as principal of the Agricultural College. His charming daughter Kana won the heart of Dr Rabindranath Som, a veterinarian who weathered the predictable Ghoti Bangal storm to win her hand in marriage.

When my parents Jyotsnamay and Manashi Ray visited us, we couldn’t visit Patishwar in Rajshahi district, where my maternal grandfather Atul Sen had worked with Rabindranath Tagore before he was arrested for revolutionary activities with Anushilan Samiti, and exiled to Kutubdia, an isolated island in the Bay of Bengal. As a headmaster, he had given shelter to Jatirindranath Mukherji, popularly known as Bagha Jatin[4].

It was a breezy day when my octogenarian father revisited Faridpur Zilla School. The colonial bungalow had acquired a fresh coat of terracotta paint. Finding his way to the headmaster’s room, he announced with a lump in his throat that history had been rewritten, boundaries redefined and new national identities forged since 1923, the year he had matriculated.

The headmaster, delving through yellowing files, fished out the matriculation results for that year. My father’s face was that of an excited school boy impatient to show off his prowess: “Look at my maths marks! Oh yes, my English scores were a trifle lower than expected because I had a touch of fever, but look at Jasimuddin’s marks in English! Thank God, he passed it.” We looked around in hushed surprise. This isn’t The Jasimuddin, the beloved poet of Bangladesh? “But of course,” my father responded. “Jasim’s weakness in English was my strength!”

Dhaka was also personally fulfilling as my doctoral studies, which I had carried across three continents, found fruition at last! On another front, I met with success in gaining the confidence and blessings of Firoza Begum, the legendary exponent of Nazrul Geeti.

The songs of Kazi Nazrul Islam were a great favourite of my father. He often hummed those made famous by Firoza Begum. Since I had trained in Tagore songs from age five, I never aspired to master the distinctly different style of rendition. A chance encounter with the golden voice revived this desire. Firoza Begum bluntly refused. When I persisted, she wanted to hear me sing a few Tagore songs.

One morning I mounted three flights of steps, harmonium on my driver’s shoulder, to enter her flat with apprehension. At her bidding, I sang four songs of Tagore. She heard me without any comment, then she asked why I hadn’t been singing for Bangladesh television. My relief was palpable! I had passed her test.

Over the next two years, my weekly classes with her extended well beyond the music lessons to serious discussions on life itself and the meaning of religion. What began as a guru-shishya[5]relationship, transcended to deep friendship. She declined any remuneration and dearly wished that I should cut a disc. This wish of hers came true only when Debojyoti Mishra heard me and decided to record my Nazrul-songs for Times Music in 2016.

Food is perhaps the first face of culture. So please share with us some of your culinary adventures. Or should I say ‘fishy’ stories?

Adventures? I could talk about the chapli kebabs in Pakistan, or about putting samosas in Bake Sales. I could tell you about making rasgullas from powder milk. I could even tell you about our gardener in Laos who merrily collected every scorpion and caterpillar that came his way, “for snacks,” he told me. But let me focus on fish.

The very first party I hosted at home in Brazil led me to seek substitutes for Indian ingredients. Fish of course had to be on the menu, mustard fish at that. I had already learnt from the Brazilian ambassador in Delhi that surubim, being boneless, was the most suited for curries. So surubim it was for months until the day I had to go to the fishmongers – and found it was a monster of a whale!

In Pakistan, traversing the arid countryside of Sind, the train would stop at stations where fillets of pala were being shallow fried on large skillets. Savouring its delicate flavour we went into a discussion on the merits of pala versus hilsa. Both have a shiny silver body with thin bones, both swim upstream against current. The taste of hilsa steam-cooked in mustard sauce is a super delight in both Dhaka and Kolkata. There of course the discussions are on the merits of the hilsa from Padma and Ganga respectively.

In Laos I once called the plumber to ease the draining of the bathtub since the pipe had got clogged. He arrived with a live fish in a plastic bag and promptly emptied it into the pipe. It would eat through the slush as it travelled through the pipe, he assured me!

Post retirement, Himachal settled to honing his culinary skills. Cooking, which he had started in Ottawa, became his lasting hobby. He would shop for fish in C R Park or INA Market[6]. He would pore over cookbooks and plot innovative recipes. “Cooking,” he was quoted in Outlook magazine, “is art thought out with palate.” And his piece de resistance was the salmon baked whole.

Which was your most cherished, or striking, brush with celebrities in world history?

At one of the finest dinners in Copenhagen I found myself seated next to a countess. She invited me to visit her since she lived in the neighbourhood. The next day a liveried man arrived to escort us to an imposing manor house. We were welcomed with sherry and we had to select a card from a silver salver with the name of our partner for the dinner. I was escorted by a handsome young man who floored me when we exchanged names. He was the descendent of Count Leo Tolstoy!

Another memorable encounter was with a person straight out of the history books. I was strolling in a forested park outside Copenhagen. I noticed with a shock that I was looking into a glass topped coffin. The aristocratic face inside had an aquiline nose and a goatee that lent a refinement to the visage that still sported a faint smile. The starched lace collar was held in place by a jewelled button that showed impeccable taste. But the elegant hands tapered off to skeletal fingers, and the feet too had become skeletal.

The plaque at the bottom of the coffin informed us that this was James Hepburn, the Earl of Bothwell, with whom Mary, Queen of Scots had fallen in love. It was a fatal attraction since both were married. But soon her husband, Lord Darnley, the father of her son James, the future king of Scotland and England, was mysteriously burnt down in a manor, and Bothwell was granted a divorce. However, their marriage incensed Catholic Europe, so Mary gave herself up to buy the release of Bothwell, who fled to Denmark.

‘Whoever marries your mother is your father’: this dictum defines the acceptance of whatever political dispensation you are forced to live with, at home or abroad. So how did you cope with a turmoil like Emergency or antagonism in Islamabad?

We had returned to Delhi in the midst of Emergency. We felt some relief to see trains running on time and punctuality being maintained in government offices. Corrupt officers were being hauled up and over-population being addressed. But the atmosphere was sombre and conversations hushed. The deep scar left by the Emergency saw Indira Gandhi being swept out of power the following year.

In Islamabad tension had mounted when I arrived over the imminent execution of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto[7]. Our residence had become the favourite watering hole for Indian and international journalists who knew Himachal from his Delhi days. Animated discussions over drinks were followed by quick despatches typed out on my rickety typewriter. Unending speculations on the unfolding drama had kept us on tenterhooks. Then one morning in April 1979, the phone rang to say, “It’s done.” [8]

How did Italy change your life?

Italy was easily the best posting of my life in embassies, not only because of its rich history. There I found Italian artists painting inspired by Tagore’s lyrics, and singers like Francesca Cassio singing Alain Danielou’s translations. What made them take it on? The question led me to rediscover Tagore.

My singing of Rabindra Sangeet also found recognition in Rome. My first CD album was released there. I was in many concerts. It was so fulfilling when my translation of Tagore’s lyrics into English found appreciation. Tagore himself believed that his songs were ‘real songs’ with emotions that speak to all people. I began translation in earnest. And that led me to write Rabindranath Tagore: The Singer and his Song (Penguin 2009). The book, with my translation of 50 Tagore songs, was considered very useful to many performing artistes who could understand and represent Tagore better in their art forms.

Please tell us about growing up with Tagore.

Like many girls in Kolkata I began learning Rabindra Sangeet from the age of five. Over the years the songs grew on me. The unique lyrics conveying a gamut of emotions spoke to me when I was far away on postings abroad. I continued my practice of the music through the years and felt vindicated when I got the opportunity to perform to appreciative audiences abroad and back in India.

Why did you work on his songs rather than his poems or stories?

There’s something compelling about Tagore songs. Remember that Gitanjali, which won him the Nobel, was a collection of ‘Song Offerings.’ Songs had given Tagore the strength to ride over the tragedies that had beset his life. They not only helped him express his grief over the deaths and suicides in his family, they were also his mode of expressing his frustration over the political situation that obtained then. And he felt his songs would help others too. “You can forget me but not my songs,” he had written.

Did you ever feel the need to jazz up the songs for Western audiences?

Tagore’s songs are like the Ardhanariswar[9] – the lyrics and the music are inseparable. The copyright restrictions that prevailed after this death did not allow translations. And that was a handicap since his music cannot be appreciated without comprehending his lyrics which are an expression of his creative thoughts.

I would say his songs have near-perfect balance between evocative lyrics, matching melody and rhythmic structure. And the incredible variety of his musical oeuvre touches every emotion felt by any human soul, without jazzing up.

Tagore’s songs are the national anthem of India and Bangladesh, and have also inspired that of Sri Lanka. But will his internationalism hold up with the change of order indicated by the recent developments on the subcontinent?

Tagore was known to be anti-nationalistic. He believed no man-made divisions can keep people segregated. He did not agree with the Western concept of ‘nation,’ he was an internationalist who accepted the ideals of democracy – ‘aamra sabai raja’[10], of gender equality – ‘aami naari, aami mohiyoshi’[11]; indeed, in equality of humans. What he wrote in lucid Bengali suited every mood. Georges Clemenceau, who was the Prime Minister of France for a second time from 1917 to 1920, had turned to Gitanjali when he heard that World War I had broken out. Even today people can relate to what he wrote.

How did all the hop skip and jump shape the feminist within Reba Som?

The wives of Foreign Service officers are often seen as decorative extensions of their spouses. People only saw the glamour we enjoyed on postings abroad, not the heartbreaks and disappointments we battled. Despite their qualifications the wives were not allowed to work abroad. Instead they had to be perfect hostesses: clad in colourful Kanjeevarams they had to prepare mounds of samosas and gulab jamuns.

But there was little recognition, appreciation or compensation by the Ministry of External Affairs of all the hard work and struggle they put in. To settle down in different postings in rapid succession. To host representational parties where they had to conjure Indian delicacies with improvised ingredients. To raise disgruntled children on paltry allowances.

Once, as the Editor of our in-house magazine, I had floated a questionnaire to all the missions abroad asking about the changing perceptions of the Foreign Service wives. That had opened a Pandora’s Box. Eventually in response to our requests the Ministry relaxed service conditions and allowed the wives to work abroad if they had the professional qualifications and received the host country’s permission. This was a veritable coup!

My own act of rebellion was accepting the Directorship of the Tagore Centre ICCR Kolkata (2008-13) after we returned to Delhi on Himachal’s retirement. It became a challenge for me to try and get the Tagore Centre on the cultural map of Kolkata, proving to myself and my disbelieving family in Delhi that it was possible!

[1] Somewhat like a Chinese collared coat

[2] Molasses

[3] Ghoti – People from West Bengal state in India

Bangal – People from Bangladesh

[4] Bagha Jatin or Joyotinadranth Mukherjee (1879-1915) was a famous name in the Indian Independence struggle

[5] Teacher-student

[6] Markets in Delhi

[7] Zulfikar Ali Bhutto(1928-1979) was the fourth president of Pakistan and later he served as the Prime Minister too.

[8] Bhutto was executed on 4th April 1979

[9] Half man half woman

[10] We are all kings

[11] I am a woman, noble and great

Ratnottama Sengupta, formerly Arts Editor of The Times of India, teaches mass communication and film appreciation, curates film festivals and art exhibitions, and translates and write books. She has been a member of CBFC, served on the National Film Awards jury and has herself won a National Award.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International